Want to join in? Respond to our weekly writing prompts, open to everyone.

The Long Road of Sons and Daughters: Learning to Run the Race Set Before Us

from Douglas Vandergraph

There is a moment that comes to nearly every human life when the soul begins to realize that faith is not merely something we talk about, but something we must live through with endurance. Hebrews 12 opens with imagery that feels almost cinematic when you slow down enough to truly see it. The writer invites us to imagine ourselves running a race, but not a quiet solitary jog through empty countryside. Instead we are running inside a vast stadium surrounded by what Scripture calls a great cloud of witnesses. These witnesses are the faithful who came before us, the men and women whose lives were marked by courage, perseverance, and trust in God even when their circumstances seemed impossible. Their presence is not meant to intimidate us, but to remind us that we are part of something larger than our own short lifetime. Faith is not a private hobby practiced in isolation; it is a living story stretching across centuries, carried forward by one generation after another. Every believer who has ever trusted God through hardship becomes part of that cloud. And when we begin to understand this picture deeply, we start to realize that our own lives are not random or unnoticed but connected to a sacred unfolding story that continues to move forward through us.

The race described in Hebrews 12 is not about speed, and it is certainly not about comparison. One of the subtle mistakes many people make in their spiritual lives is assuming that faith should look impressive to others. We sometimes imagine that the strongest believers are the ones who appear to move effortlessly through life, never stumbling and never struggling. But the language of endurance tells a different story entirely. Endurance assumes difficulty, resistance, and moments where continuing forward requires deep inner resolve. The race of faith is not won by those who sprint early and collapse later, but by those who continue placing one step in front of the other when their legs feel heavy and their breath feels short. In other words, Hebrews 12 speaks to the long obedience of the soul. It acknowledges that the journey with God often unfolds across years of quiet perseverance rather than dramatic moments of triumph. When people hear the phrase “run with endurance the race set before us,” they sometimes overlook the deeply personal part of that sentence. The race set before us is not identical for every person. Each life carries its own terrain, its own hills, its own unexpected storms, and its own moments where the path feels lonely. Yet God remains present in every one of those landscapes, guiding the runner who continues forward in trust.

The writer of Hebrews also introduces one of the most liberating ideas in the entire passage when he tells us to lay aside every weight and the sin that clings so closely. The difference between those two categories is worth careful reflection. Sin is the obvious burden that pulls us away from God’s design for our lives. But weights can be more subtle. A weight might not be inherently sinful, yet it still slows our progress. Sometimes weights appear in the form of distractions that consume our time and attention. Other times they appear as fears we have carried for so long that they begin to feel normal. Many people unknowingly run their race while dragging emotional baggage that God never intended them to carry. The invitation of Hebrews 12 is not simply to try harder, but to travel lighter. When we release the unnecessary burdens that entangle our hearts, the journey with God begins to feel different. Faith becomes less about grinding effort and more about clear direction. It becomes possible to see the path ahead because our vision is no longer clouded by everything we have been dragging behind us. This idea alone has the power to transform how we think about spiritual growth. The goal is not to prove our strength by carrying every burden imaginable, but to trust God enough to release what no longer belongs in our hands.

At the center of the entire passage stands a single phrase that anchors everything else: looking to Jesus, the author and finisher of our faith. This statement contains a depth that cannot be exhausted by a quick reading. To call Jesus the author of faith means that faith itself begins with Him. Our relationship with God is not something we invent through our own spiritual creativity. It begins because God first reached toward us. Long before we ever took our first uncertain steps toward faith, Christ had already stepped into human history to make reconciliation possible. But the passage goes even further by calling Him the finisher of our faith. This means that the story does not end with our fragile beginnings. Jesus does not merely start the work and then leave us alone to complete it. He remains present throughout the entire process, guiding, shaping, correcting, and strengthening the believer as life unfolds. When people feel overwhelmed by the weight of their own imperfections, this truth becomes profoundly comforting. Faith is not sustained by our perfection but by Christ’s faithfulness. Our role is not to manufacture spiritual power but to keep our eyes oriented toward the One who carries the story forward.

The writer then reminds us that Jesus endured the cross for the joy set before Him. This phrase has puzzled many readers over the centuries because the cross represents unimaginable suffering. Yet Hebrews insists that joy existed on the horizon beyond that suffering. The joy was not the pain itself but the redemption that would flow from it. Jesus saw what would be accomplished through His sacrifice. He saw the restoration of humanity’s relationship with God. He saw the possibility of millions of lives being transformed through grace. He saw people who had been trapped in despair discovering hope again. When Christ looked toward the cross, He was looking through the pain toward the restoration it would bring. This perspective carries enormous implications for our own struggles. When believers face seasons of hardship, we often interpret those moments as meaningless suffering. But Hebrews invites us to consider that God may be working toward outcomes we cannot yet see clearly. Faith allows the soul to hold onto hope even when the present moment feels heavy. It does not deny the difficulty of the road, but it refuses to believe that the road ends in darkness.

Another powerful dimension of Hebrews 12 emerges when the writer begins to speak about discipline. In modern culture the word discipline often carries negative associations. Many people hear the term and immediately imagine punishment or rejection. But the passage frames discipline in an entirely different light by connecting it to the identity of being God’s children. Discipline, according to Hebrews, is evidence of belonging. Just as a loving parent guides and corrects a child in order to help them grow into maturity, God shapes the lives of those He loves. This process is rarely comfortable in the moment. Growth seldom is. Yet the writer insists that discipline ultimately produces a harvest of righteousness and peace for those who have been trained by it. The language here is agricultural and patient. Harvests do not appear overnight. Seeds are planted, seasons pass, storms come and go, and only after time does the fruit begin to appear. Spiritual maturity follows a similar rhythm. God’s work in our lives unfolds gradually through experiences that stretch our character and deepen our trust. The discipline we experience today often becomes the strength we depend upon tomorrow.

This understanding of discipline helps believers reinterpret many of life’s difficulties. Instead of seeing hardship as evidence that God has abandoned us, Hebrews suggests that some challenges may actually be part of God’s refining work. This does not mean that every painful experience is directly orchestrated by God, but it does mean that God is capable of bringing growth out of circumstances that initially appear discouraging. The soul that learns to trust God through these seasons becomes resilient in a way that cannot be manufactured through comfort alone. Over time the believer begins to recognize that faith is not fragile after all. It can withstand storms because it is rooted in something deeper than temporary circumstances. The Christian life therefore becomes less about avoiding difficulty and more about discovering God’s presence within it. When we begin to view our struggles through this lens, even the hardest seasons can take on new meaning. The road may still be difficult, but it is no longer empty of purpose.

Hebrews 12 continues by encouraging believers to strengthen their weak hands and steady their trembling knees. The imagery here suggests a community that supports one another through the race of faith. Christianity was never intended to be lived entirely alone. The early believers understood that encouragement, accountability, and shared wisdom were essential for spiritual growth. When one person grows weary, another can remind them why the journey matters. When someone begins to lose heart, another voice can gently guide them back toward hope. This communal dimension of faith reflects the heart of the gospel itself. God did not design humanity for isolation. We flourish when we walk together toward the same source of life. The call to strengthen one another therefore becomes part of the race itself. Every act of encouragement becomes a way of helping someone else continue forward.

The writer then urges believers to pursue peace with everyone and to pursue holiness without which no one will see the Lord. These two pursuits belong together more closely than many people realize. Peace reflects how we relate to others, while holiness reflects how we orient our hearts toward God. Both are necessary because faith expresses itself in both directions. A person cannot claim deep spiritual devotion while consistently creating division and hostility around them. At the same time, peace that ignores the call to holiness becomes shallow and temporary. Hebrews invites believers into a life where inner transformation and outward relationships move in harmony. The more a person grows in closeness with God, the more their character begins to reflect the patience, compassion, and integrity that Jesus displayed. Holiness therefore becomes less about rigid rule-keeping and more about allowing God’s presence to reshape the entire landscape of the soul.

The passage also contains a sober warning about bitterness. The writer describes bitterness as a root that can grow quietly beneath the surface and eventually cause trouble for many people. This imagery is remarkably accurate to real human experience. Bitterness rarely appears suddenly in full form. Instead it begins as a small wound that remains unresolved. If that wound is continually revisited without healing, it begins to deepen. Over time the bitterness spreads outward, influencing how a person interprets other relationships and circumstances. What started as a single hurt eventually colors the entire emotional landscape of a life. Hebrews calls believers to remain vigilant against this process because bitterness can slowly erode joy, gratitude, and trust. The antidote is not pretending that pain never occurred, but bringing those wounds honestly before God so that healing can begin. Forgiveness does not erase the past, but it prevents the past from imprisoning the future.

One of the quiet turning points in Hebrews 12 arrives when the writer contrasts two mountains that represent two entirely different spiritual realities. The first mountain is Sinai, the place where the law was given amid thunder, fire, darkness, and trembling. The imagery is intense and overwhelming because Sinai represented a moment when humanity encountered the holiness of God in a way that revealed how distant and unapproachable that holiness seemed. The people who stood at the base of that mountain were terrified, not because God desired to frighten them, but because the raw power of divine holiness exposed the limitations of human righteousness. Even Moses, who stood closer to God than almost anyone in that moment, described himself as trembling with fear. Sinai revealed something profoundly true about the human condition: left to our own efforts, we cannot climb high enough to reach God. The law was never meant to serve as a ladder by which humanity could earn its way into heaven. Instead it revealed the depth of our need for grace.

But Hebrews does something remarkable after describing Sinai. It tells believers that they have not come to that mountain. Instead they have come to Mount Zion, the city of the living God, the heavenly Jerusalem. The atmosphere shifts completely when the writer begins describing this second mountain. Instead of thunder and terror, there is celebration. Instead of distance, there is welcome. Instead of trembling fear, there is joyful assembly. Zion represents the fulfillment of what Sinai pointed toward. Through Christ, believers are invited into a relationship with God that is no longer defined by separation but by reconciliation. The writer describes an innumerable gathering of angels, the assembly of the firstborn who are enrolled in heaven, and God Himself standing at the center of it all. It is an image of belonging that stretches beyond anything the human imagination normally conceives. Faith, according to Hebrews, is not merely about moral improvement or spiritual discipline. It is about being welcomed into a living community that spans heaven and earth.

At the center of this gathering stands Jesus, described as the mediator of a new covenant. The word mediator carries immense weight because it captures the bridge that Christ forms between God and humanity. Under the old covenant, the people relied on priests and sacrifices that had to be repeated continually. Each sacrifice pointed toward the seriousness of sin but could never permanently remove its power. The blood of animals symbolized atonement, yet it remained only a shadow of something greater that was still to come. When Hebrews speaks of the sprinkled blood of Jesus that speaks a better word than the blood of Abel, it is drawing on a story from the earliest pages of Scripture. Abel’s blood cried out from the ground as a testimony to injustice and violence. The blood of Christ, however, speaks a different message entirely. It speaks forgiveness rather than accusation. It speaks reconciliation rather than judgment. It speaks restoration rather than exile. Through Christ, the relationship between God and humanity is not merely patched together but transformed into something entirely new.

The writer then delivers a warning that carries both urgency and compassion. He urges readers not to refuse the One who is speaking. Throughout the history of faith, God has spoken in many ways. Sometimes His voice came through prophets, sometimes through Scripture, sometimes through quiet conviction within the human heart. But Hebrews insists that the clearest and most decisive expression of God’s voice came through Jesus Christ. To ignore that voice is not simply to miss a helpful piece of advice; it is to turn away from the very source of life. Yet the warning is not meant to produce fear alone. It is meant to awaken awareness. God continues to speak because He desires relationship. The call to listen is therefore an invitation to remain open to the transformation that God is continually offering.

The passage concludes with a powerful image of God shaking the heavens and the earth. This idea may initially sound unsettling, but its deeper meaning becomes clearer as the writer explains it. The shaking represents the removal of what cannot last so that what is truly permanent can remain. Much of what humans build throughout life feels solid and secure in the moment, yet history repeatedly reminds us how fragile those structures can be. Wealth, status, cultural trends, and political systems all rise and fall across generations. Hebrews invites believers to anchor their lives in something that cannot be shaken. The kingdom of God stands beyond the instability of human systems because it is rooted in God’s eternal character. When believers place their hope in that kingdom, they begin to experience a stability that circumstances alone cannot provide.

Receiving this unshakable kingdom leads naturally to gratitude. The writer calls believers to respond with reverence and awe, recognizing the holiness of the God who welcomes them into His presence. Reverence does not mean shrinking away in fear. Instead it reflects a deep awareness of the sacredness of the relationship we have been invited into. When someone truly understands the grace they have received, gratitude becomes the natural posture of the heart. Worship stops being a weekly ritual performed out of obligation and becomes a sincere response to the beauty of God’s character. The more deeply we recognize what Christ has done, the more naturally reverence flows from within us.

One of the quiet miracles of Hebrews 12 is how it reshapes the way believers think about their own lives. Instead of viewing life as a random series of disconnected events, the passage reveals a larger narrative unfolding beneath the surface. Every challenge becomes part of a race being run. Every moment of discipline becomes part of a training process shaping the soul. Every act of encouragement becomes part of a community journeying together toward the same destination. And every step of faith becomes part of a story that stretches from the earliest witnesses of Scripture all the way into eternity. When people begin to see their lives through this lens, the ordinary moments of daily existence take on deeper meaning. The quiet decisions we make, the kindness we offer, the patience we practice, and the trust we extend toward God all become threads woven into a much larger tapestry.

There is also something profoundly comforting about the realization that the race of faith does not depend on flawless performance. Hebrews never asks believers to run perfectly. Instead it asks them to run faithfully. The difference between those two ideas is enormous. Perfection focuses on avoiding every possible mistake. Faithfulness focuses on continuing forward even after mistakes occur. The writer of Hebrews understood that human beings stumble. That is precisely why he continually directs attention back toward Jesus. When our eyes remain fixed on Christ, failure no longer becomes the final word. Grace remains larger than our missteps, and the path forward remains open.

As believers move through life, they eventually begin to notice that the race described in Hebrews 12 contains seasons of both intensity and quiet endurance. Some moments feel dramatic and decisive, like crossing a mountain pass where the view suddenly expands. Other moments feel ordinary, like walking mile after mile through terrain that looks almost unchanged. Yet both types of seasons play essential roles in the formation of faith. The dramatic moments remind us of God’s power and presence in unmistakable ways. The quiet stretches teach us perseverance and trust. Over time the believer begins to recognize that God is present in both kinds of seasons. The mountaintop and the valley both become places where the soul learns to depend on Him.

The imagery of the great cloud of witnesses also begins to feel more personal as life unfolds. When we read about the faithful figures described earlier in Hebrews, they may initially seem distant and almost mythical. But as the years pass, we begin to encounter people in our own lives who embody similar courage and devotion. Perhaps it is a mentor who quietly lived with integrity for decades. Perhaps it is a parent who endured hardship without losing faith. Perhaps it is a friend who continued to trust God through circumstances that would have broken someone else. These individuals become part of our own cloud of witnesses, reminding us that the race can indeed be finished well. Their stories encourage us to keep running when our own strength feels thin.

The invitation of Hebrews 12 ultimately leads believers toward a life of profound hope. The passage acknowledges suffering, struggle, and discipline without minimizing their difficulty. Yet it refuses to allow those realities to define the entire story. The race has a destination. The training has a purpose. The shaking has an outcome. The kingdom that awaits believers cannot be shaken because it is built upon the unchanging character of God Himself. When the soul truly absorbs this truth, anxiety about temporary circumstances begins to lose its grip. The future no longer appears as an unpredictable threat but as a continuation of the story God is already guiding.

And so the believer continues forward, sometimes running with strength, sometimes walking slowly, sometimes leaning on others for encouragement, but always moving toward the One who began the journey in the first place. The path may twist and rise in ways we did not expect, but the destination remains secure. Jesus, the author and finisher of our faith, remains ahead of us, beside us, and within us all at once. The race is not solitary, the road is not meaningless, and the finish line is not uncertain. It is held firmly within the promise of the God who calls His sons and daughters home.

Your friend, Douglas Vandergraph

Watch Douglas Vandergraph’s inspiring faith-based videos on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/@douglasvandergraph

Support the ministry by buying Douglas a coffee: https://www.buymeacoffee.com/douglasvandergraph

Financial support to help keep this Ministry active daily can be mailed to:

Vandergraph Po Box 271154 Fort Collins, Colorado 80527

The First Family and the Courage to Face Honest Questions

from Douglas Vandergraph

There are moments in every sincere spiritual journey when a person encounters a question in Scripture that feels too direct to ignore. These questions are not signs of weak faith. They are often the doorway into a deeper, more mature relationship with truth. One of those questions has circulated for generations, quietly passing between curious minds who are reading the earliest pages of the Bible and trying to understand the world they describe. The question is simple enough that a child might ask it, yet profound enough that many adults hesitate before answering it out loud. If God created Adam and Eve, and Adam and Eve had sons named Cain and Abel, then where did their wives come from? The question is not hostile toward faith. It is the natural result of reading the story carefully and wanting the details to make sense. When people finally give themselves permission to ask it openly, something important happens. Instead of weakening faith, the honest pursuit of the answer often strengthens it because it reveals the depth and realism of the biblical narrative.

The opening chapters of Genesis introduce us to the beginning of the human story. They describe a moment when humanity did not yet exist and then suddenly did. According to the biblical account, God formed Adam from the dust of the ground and breathed life into him. Shortly afterward, Eve was created as Adam’s companion, completing the first human relationship. From that point forward the story begins to move, not through abstract ideas, but through family. The Bible does not present the beginning of humanity as a mass creation of millions of people scattered across the earth. Instead, the entire human race begins with one couple. This design immediately tells us something about the way God intended human life to unfold. Humanity was meant to grow, multiply, and expand through generations of family relationships. The first two humans were not simply individuals placed on the earth. They were the starting point of a lineage that would eventually become every nation, culture, and language that exists today.

When we reach the story of Cain and Abel, the narrative focuses on two sons whose lives take very different directions. Abel becomes known for offering a sacrifice that pleases God, while Cain becomes remembered for committing the first act of murder in human history. The tragedy of that moment echoes throughout the entire biblical storyline because it shows how quickly human freedom can drift away from God’s design. After Cain kills Abel, the story continues, and that is where the question naturally arises. Cain eventually leaves and builds a life for himself, and Scripture tells us that he had a wife. For readers who are thinking carefully, the question becomes unavoidable. If Adam and Eve only had two sons, where did this wife come from?

The answer is not hidden, but it does require paying attention to what the text actually says rather than what we assume it says. Genesis does not claim that Adam and Eve had only two children. In fact, the Bible explicitly tells us that Adam had many sons and daughters over the course of his long life. The narrative names Cain, Abel, and later Seth because they play a role in the unfolding storyline, but those names represent only a small portion of the growing first family. In the earliest generation of humanity, the sons and daughters of Adam and Eve married one another because there were no other humans yet. Cain would have married one of his sisters or possibly a niece from the expanding family line that had already begun to form.

For many people in the modern world, hearing that explanation triggers an immediate sense of discomfort. Today the idea of close family marriages is both morally prohibited and genetically dangerous. However, the conditions of the earliest human generations described in Genesis were fundamentally different from the conditions we experience today. The biblical narrative presents the first humans as being created directly by God, meaning they would not have carried the layers of genetic mutation that have accumulated throughout thousands of years of human history. The genetic risks that exist in modern populations would not have been present in the same way during the earliest generations. What feels shocking when viewed through modern biological conditions would not have carried the same dangers at the very beginning of humanity’s existence.

It is also important to recognize that the moral law forbidding incest was not given until much later in the biblical timeline. Those laws appear in the Mosaic Law, many generations after the population had grown large and human societies had become far more complex. By that point in history, God established clear boundaries designed to protect both family structure and genetic health within expanding communities. In the earliest stage of humanity, however, the population had to grow from the single family that existed. The beginning of the human story required a form of family multiplication that would later become unnecessary and forbidden once the population expanded.

When we step back and look at the broader picture, the question about Cain’s wife stops being a stumbling block and becomes something else entirely. It becomes a reminder of how small the beginning of humanity truly was. The entire human race started with one couple and one family. Every civilization, every culture, every language, and every nation that has ever existed can trace its distant roots back to that original beginning. The scale of that truth is almost impossible to fully grasp. Billions of human lives have unfolded across thousands of years, yet all of them ultimately connect to the same starting point described in the opening chapters of Genesis.

That realization reveals something profound about the character of God. God is not intimidated by small beginnings. In fact, throughout Scripture we see that God repeatedly chooses small beginnings as the starting point for extraordinary outcomes. The pattern appears so consistently that it becomes one of the defining characteristics of how God works in the world. The human race begins with two people. The nation of Israel begins with one man named Abraham who is wandering through a foreign land with no children and no clear future. The ministry of Jesus begins with a small group of ordinary followers who have no political power, no military strength, and no influence within the institutions of their time. Yet from those small beginnings come movements that reshape the course of human history.

This pattern carries a powerful message for anyone who has ever felt like their life started too small to matter. Many people quietly believe that greatness belongs only to those who began with visible advantages. They assume that meaningful impact requires the right background, the right resources, or the right connections. But the biblical story consistently challenges that assumption. God often chooses beginnings that appear ordinary, fragile, or even unlikely. The smallness of the beginning is not a weakness in God’s design. It is often the very stage on which His creativity and power become most visible.

When people wrestle with the question of Cain’s wife, they are often trying to resolve a detail within the story. What they sometimes miss is the larger truth the story reveals about how God builds history. God begins with something small and allows it to grow. The first family becomes a growing community. The community becomes tribes and nations. Those nations develop cultures, languages, and histories that spread across the earth. What began quietly in a garden eventually becomes the entire human civilization.

The same principle appears again and again throughout the rest of Scripture. God rarely introduces His plans with overwhelming force or dramatic spectacle. Instead, He plants seeds. Those seeds grow slowly, often in ways that are not immediately visible to the people living through the early chapters of the story. Yet as time passes, the full scope of what God began becomes impossible to ignore.

For individuals living in the present day, this truth carries deep encouragement. Many people look at their current circumstances and feel like their starting point is too limited to produce anything meaningful. They see their background, their struggles, their past mistakes, or their lack of resources, and they quietly conclude that their story cannot possibly grow into something significant. But the opening chapters of the Bible tell a different story. They reveal a God who specializes in beginnings that appear small.

As the story of humanity continues to unfold through Scripture, the pattern that begins in Genesis becomes easier to recognize. God does not rush the development of the human story, and He does not seem concerned with whether the beginnings look impressive to human observers. The first family grows quietly across generations, and from that growth entire civilizations eventually appear. What begins with Adam and Eve expands outward through time in ways that those first humans could never have imagined while they were standing in the early chapters of their existence. This is part of the beauty of the biblical narrative. It does not pretend that history began with grandeur and spectacle. Instead, it shows that the foundation of everything we know today began with a simple family relationship between a man and a woman placed in a garden by their Creator. When we allow ourselves to see that clearly, the scale of what God accomplished through such a small beginning becomes one of the most inspiring elements of the entire biblical story.

The question about Cain’s wife therefore becomes more than a historical curiosity. It becomes an invitation to think about the nature of beginnings themselves. Every great story in human history begins somewhere small. Before a nation exists, there is a group of families learning how to live together. Before a movement spreads across continents, there is a small group of people sharing an idea. Before a life of influence touches others, there is often a quiet season where growth happens out of sight. The early chapters of Genesis reveal that God is completely comfortable working in those quiet beginnings. He does not appear to be in a hurry. Instead, He allows time, relationship, and human development to gradually unfold the world that He has set into motion.

For many people, one of the most difficult parts of life is learning to trust the early chapters of their own story. It is easy to admire the finished outcomes we see in history, but much harder to remain patient during the slow growth that produces those outcomes. We live in a world that celebrates visible success, quick results, and dramatic achievements. Because of that cultural pressure, people sometimes look at their own lives and feel discouraged when progress seems slow or ordinary. Yet the biblical pattern suggests that God rarely begins His greatest works with immediate visibility. He begins quietly, often through circumstances that appear almost too small to matter.

Consider again the first family described in Genesis. Adam and Eve could not possibly have imagined the scale of what would grow from their lives. They could not see cities rising across continents. They could not envision languages forming, cultures developing, and generations stretching thousands of years into the future. Yet every one of those developments traces back to the simple reality that God began the human story with them. What looked like a modest beginning became the foundation of everything that followed.

This truth carries profound meaning for people who sometimes feel like their lives are unfolding in quiet or unnoticed ways. Many individuals live faithfully, work diligently, love their families, and pursue purpose without receiving the recognition that the world often associates with significance. They may wonder whether their efforts truly matter or whether their story will ever grow into something meaningful. The early chapters of Genesis offer a reassuring perspective in moments like that. They remind us that the size of a beginning does not determine the value of what will grow from it.

The story of Cain and Abel also illustrates another important dimension of the human journey. From the very beginning, human history contains both beauty and brokenness. The first family experiences love, creativity, and growth, but it also encounters jealousy, violence, and grief. Abel’s death reveals that humanity’s relationship with God has already been disrupted by sin. Yet even in the presence of tragedy, the story does not stop. Life continues. Families continue. The human story moves forward. This persistence is not accidental. It reflects the determination of God to continue working through humanity even when humanity struggles with its own weaknesses.

That resilience within the biblical narrative carries an important message for anyone who feels discouraged by their own mistakes or by the brokenness they see in the world around them. The presence of failure does not end the story. God continues to work through imperfect people in imperfect circumstances. The unfolding of human history demonstrates that God’s purposes are not easily stopped by the setbacks that occur along the way. Even when individuals falter, the larger story continues to move toward the future that God is guiding.

When we think about the expansion of humanity from that first family, it becomes clear that time plays an essential role in God’s design. Growth takes time. Generations build upon the lives of those who came before them. The human story unfolds gradually rather than instantly. This rhythm appears throughout the Bible, reminding us that God often chooses to work through processes rather than shortcuts. Seeds grow into trees over seasons. Families grow into communities over generations. Movements grow into transformations over decades and centuries.

Understanding this rhythm can help people find peace during seasons when their own progress feels slow. The biblical narrative does not promise that meaningful growth will always be immediate. Instead, it shows that God is deeply committed to the long arc of history. What begins quietly today may produce consequences far beyond what anyone currently sees. The seeds planted in one generation may bear fruit in another. Faithfulness in small moments may eventually shape lives in ways that are impossible to measure at the time they occur.

When people ask where Cain found his wife, they are sometimes looking for a problem within the text. What they often discover instead is a reminder of how remarkably small the beginning of humanity truly was. From one family came the entire human race. From that small beginning came every relationship, every society, and every chapter of history that followed. The scale of that expansion reflects the creative power of the God who set the story in motion.

This understanding invites a different way of looking at our own lives. Instead of measuring significance only by what is visible today, we can recognize that the beginnings we are living through may hold possibilities that extend far beyond the present moment. The God who began humanity with two people in a garden is still capable of working through the quiet beginnings that exist in ordinary lives. What appears small from a human perspective may be the starting point of something far more meaningful than anyone can currently imagine.

The biblical story encourages us to approach honest questions without fear. Questions do not weaken faith when they are asked sincerely. Instead, they often lead to deeper understanding. The question about Cain’s wife reminds us that the Bible invites thoughtful reading and honest reflection. When we engage with Scripture in that way, we discover that its message is not fragile. It is strong enough to withstand curiosity, examination, and careful thought.

In the end, the early chapters of Genesis are not merely explaining how humanity began. They are revealing the character of the God who began it. He is a Creator who works patiently through time. He is a God who sees potential in beginnings that appear small. He is a God who continues to guide the unfolding of the human story even when that story includes moments of confusion or struggle.

The human race began as one family and expanded into the vast tapestry of lives that fill the earth today. That expansion reminds us that beginnings do not need to be large in order to matter. What matters is the presence of the Creator who breathes life into the beginning and allows it to grow.

If the story of humanity could grow from a single family into the entire world we see today, then the beginnings unfolding in our own lives may also carry possibilities that reach further than we currently understand. The God who started the human story has not stopped writing it. Every life is part of that ongoing narrative, and each new chapter continues to reveal the quiet, patient creativity of the One who began it all.

Your friend, Douglas Vandergraph

Watch Douglas Vandergraph’s inspiring faith-based videos on YouTube https://www.youtube.com/@douglasvandergraph

Support the ministry by buying Douglas a coffee https://www.buymeacoffee.com/douglasvandergraph

Financial support to help keep this Ministry active daily can be mailed to:

Vandergraph Po Box 271154 Fort Collins, Colorado 80527

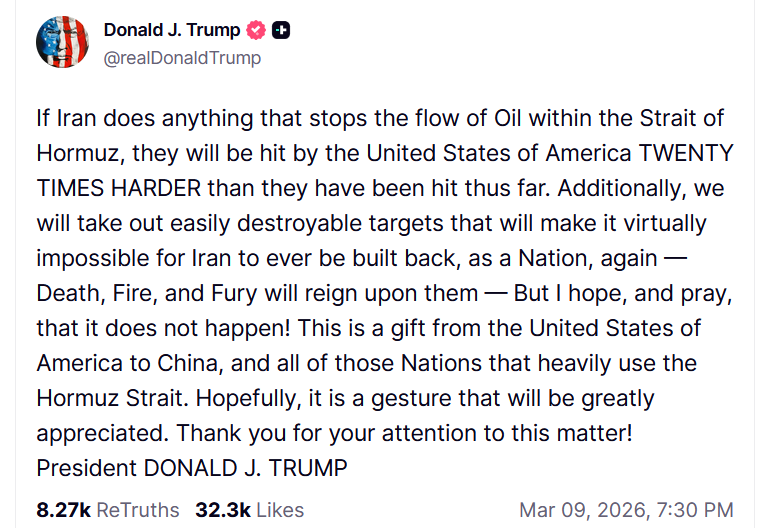

This is NOT Just War in Practice

“We will take out easily destroyable targets that will make it virtually impossible for Iran to ever be built back, as a Nation, again — Death, Fire, and Fury will reign [sic] upon them.”

This is NOT the Just War Tradition in practice. This is NOT how this works. It's simply not.

At best, this most certainly would violate the jus in bello tenets of distinction, proportionality, and military necessity. At worst, the United States would abdicate any claim to moral authority among the nation.

Clearly the regime in Iran is demonic and horrid, one of the worst in the world; however, from a Christian perspective all is NOT fair in love and war. It never has been. These are not the tactics of the United States of America. These are not the tactics of a nation behaving with honor. These are the tactics of treachery. These are the tactics of the ungodly.

You cannot rationalize this approach under any historic Christian understanding of the Just War Tradition. It is inexcusable. God, save us.

#history #politics #theology

Street Scene

from Tuesdays in Autumn

Until yesterday, it had been over twenty years since the means and opportunity last aligned such that I bought a painting. I'd been in Chepstow on Saturday morning, doing my usual rounds of the town's 'thrifting' locations, when, at the Red Cross charity shop I saw the walls lined with a dozen or more paintings and drawings. One in particular caught my eye — a street scene (Fig. 15) with a French look about it. The price was £100: high for a charity shop; not so high for a unique work of art. Unwilling to act on an immediate impulse, I decided to think it over.

Yesterday was a day off work. I'd been meaning to gather together a batch of records and CDs that had become surplus to requirements, and donate them somewhere. That somewhere, I realised, could be the Red Cross shop with the paintings. I dropped off the music and paid £103: for the painting plus a shirt I’d noticed while I was waiting for it to be taken down from the wall. The shop manager told me that the artworks had all come from the collection of a local ceramicist, who had been downsizing in advance of a move.

The painting is in oils or some other thickly-applied paint on a tatty old piece of board: there's some damage at its edges and at least one hole right through it. The frame is a somewhat distressed wooden one painted an unappealing shade of grey. The picture is signed and dated at the bottom right, though not altogether legibly. The artist's name was Peter S[omething] and the painting was made in (I think) '52. I've hung it at the top of the stairs, where a framed collage had previously been. I very much like how it looks there.

Elsewhere in Chepstow on Saturday I bought three '80s LPs for a tenner. These, I realised later, were linked by the letter 'L': the self-titled debut album by The Lounge Lizards; Will the Wolf Survive by Los Lobos; and Lyle Lovett & his Large Band. I was unfamiliar with all three but was happy to take a chance on them given their inexpensiveness. This was a trio that proved to be a decidedly mixed bag.

I'd seen or heard any number of mentions of the Lounge Lizards over the years without ever knowingly hearing a note of their music. On first acquaintance I really enjoyed the album: '50s jazz flavours served up with post-punk avant-garde attitude. An accomplished effort though it was, the Los Lobos record wasn't well-aligned with my current tastes and I didn't take a shine to it. As for the Lyle Lovett disc, it was a frustrating case inasmuch as I loved about half of it and disliked the rest: I may get a CD copy so I can more readily skip the tracks I don't care for.

I greatly admired Maria Stepanova's non-fiction opus In Memory of Memory when I read it a few years ago. Seeing a novel of hers (The Disappearing Act) has been newly published in English I thought I'd get a copy of it, and also try some of her poetry, in the shape of the 2021 collection War of the Beasts and the Animals. I read the latter (translated, like the other books, by Sasha Dugdale) on Wednesday and Thursday.

Inspired here & there by high modernism and dense with allusion, some of it felt opaque to the point of obscurity. Elsewhere were less forbidding poems based on ballads & songs, though some of those too came across like puzzles I couldn't necessarily solve. In short, although there were moments I could grasp and savour, I felt like its demands often exceeded my limited abilities as a reader.

Mike Elgan Nails It

from Mitchell Report

https://elgan.com/why-you-should-love-blogs-now-more-than-ever

Why you should love blogs now more than ever

, Mike Elgan (@MikeElgan@mastodon.social) on sharkey (source)

I saw Mike's post in my timeline, and it's referenced above. While I know some people hate AI with a passion, I agree that AI content has, for the most part, made the internet harder to enjoy. I agree with his post wholeheartedly, and maybe it will bring blogs – and hearing from people on blogs – back into the spotlight.

There was a time when most blogs looked quaint and personal, reflecting the owner's personality not only in their words but in the site's visuals. I also agree with Dave Winer's views on blogs, though not the idea of leaving everything completely unedited. If by “unedited” he means honest, uncensored feelings, I'm fine with that. But I do think having an AI or another human proofread your work is usually a good idea.

When I read some of my earlier posts from my youth – about 25 years ago when I was in my mid-twenties – I often think, what did I even mean there? It may make no sense now, and when I see something like that I cringe and immediately do some blog gardening and fix it. I don't want an AI to turn everything into perfect polish, but I do want my writing to make sense. Sometimes I ramble and chase rabbits the way I do in conversation, and that can lose readers' attention. I hate walking away from someone and thinking, what were we even talking about? That was all over the place.

So yes blogs look like the are coming back and that is good thing in my opinion and Google if you listening Blogger will be 30 years old in a few years. How about doing some updates too it but keep it conservative and non AI related and keep the spirit of it alive and just bring it forward into the modern age.

#blogging #opinion

John Belushi and Frank Zappa, SNL 1978

John Belushi and Frank Zappa, SNL 1978

Control of one’s output determines artistic longevity. Is career a long arc or a series of brilliant explosions?

from  Jall Barret

Jall Barret

Tidying up

Recently, I've been struggling to figure out what I'm working on in terms of writing. February was a kick ass month where I released video projects and did nearly 60K words.

I ended up going through my entire list of open projects and discovered I had about 15 fiction projects on my plate. I also found I had writing folders I didn't recognize by code name. That and some other things made me realize I might have too much going on.

When I was making appointments with clients regularly as part of my IT job, I came to a truth that has helped me ever since. If you give someone the open ended question “when would you like to meet,” you're probably not going to get an answer any time. You've got SLAs, and they've got a hypothetical infinity to choose from.

If you instead suggest two specific times, they may accept one of them or they may propose their own. The effective range of possibility is still the same but now it doesn't look nearly as intimidating.

I've used random number generators for myself since I was a child. Assign each possibility its own number and run the RNG. Even if it picks one I decide I definitely don't want to do, running the RNG helped make that possibility real enough to turn it down.

On the other hand, it also helps to clear out the clutter.

So I made a list of all my active projects and moved the others to a folder I use for projects that are on hold.

The number is still fifteen (or fourteen depending on how you count) but now I can see it a little better.

And maybe I can make myself an RNG project picker in Python that will read project names from my fancy new table.

At the moment, the big thing is to get enough of my mental desk clean so that I can think and do a bit of writing.

#PersonalEssay

Van Voorbijgaande Aard houdt zich staande aan de toog

from Lastige Gevallen in de Rede

Vijf keer iets zwaars op de maag, graag!

Och wat zou ik graag zitten met iets zwaars op de maag ook wacht ik nog op een gulle gever zodat ik iets heb voor op mijn lever mijn dieet is zelfs zo arm dat ik geen grip meer heb op mijn twaalfvingerige darm ik zou bij god niet weten wat er nog in me zit om op te vreten de laatste keer dat ik iets te bikken kon halen was vorige week toen ik er op bed over lag te malen kon ik de vrijheid van meningsuiting maar verliezen dan kreeg ik weer iets voor mijn kiezen ik kan er heel slecht tegen dat er niks op de schaal ligt voor wikken en wegen voor de lege keukenkastjes denk ik elk etmaal weer had ik bij die gehaalde gram maar een onsje meer het enigste waar ik nog een beetje van geniet is dat mijn ongebruikte keuken er iedere dag onberispelijk uitziet door deze vorm van buitensporige verschraling val ik van lieverlee steeds vaker in herhaling

Och wat zou ik graag zitten met iets zwaars op de maag ook wacht ik nog op een gulle gever zodat ik iets heb voor op mijn lever mijn dieet is zelfs zo arm dat ik geen grip meer heb op mijn twaalfvingerige darm ik zou bij god niet weten wat er nog in me zit om op te vreten de laatste keer dat ik iets te bikken kon halen was vorige week toen ik er op bed over lag te malen kon ik de vrijheid van meningsuiting maar verliezen dan kreeg ik weer iets voor mijn kiezen ik kan er heel slecht tegen dat er weer niks op de schaal ligt voor afwegen voor de lege keukenkastjes denk ik elk etmaal weer had ik bij de gehaalde gram maar een onsje meer het enigste waar ik nog een beetje van geniet is dat mijn ongebruikte keuken er iedere dag onberispelijk uitziet door deze vorm van buitensporige verschraling val ik van lieverlee steeds vaker in herhaling

Och wat zou ik graag zitten met iets zwaars op de maag ook wacht ik nog op een gulle gever zodat ik iets heb voor op mijn lever mijn dieet is zelfs zo arm dat ik geen grip meer heb op mijn twaalfvingerige darm ik zou bij god niet weten wat er nog in me zit om op te vreten de laatste keer dat ik iets te bikken kon halen was vorige week toen ik er op bed over lag te malen kon ik de vrijheid van meningsuiting maar verliezen dan kreeg ik weer iets voor mijn kiezen ik kan er heel slecht tegen dat er weer niks op de schaal ligt voor afwegen voor de lege keukenkastjes denk ik elk etmaal weer had ik bij de gehaalde gram maar een onsje meer het enigste waar ik nog een beetje van geniet is dat mijn ongebruikte keuken er iedere dag onberispelijk uitziet door deze vorm van buitensporige verschraling val ik van lieverlee steeds vaker in herhaling

Och wat zou ik graag zitten met iets zwaars op de maag ook wacht ik nog op een gulle gever zodat ik iets heb voor op mijn lever mijn dieet is zelfs zo arm dat ik geen grip meer heb op mijn twaalfvingerige darm ik zou bij god niet weten wat er nog in me zit om op te vreten de laatste keer dat ik iets te bikken kon halen was vorige week toen ik er op bed over lag te malen kon ik de vrijheid van meningsuiting maar verliezen dan kreeg ik weer iets voor mijn kiezen ik kan er heel slecht tegen dat er weer niks op de schaal ligt voor afwegen voor de lege keukenkastjes denk ik elk etmaal weer had ik bij de gehaalde gram maar een onsje meer het enigste waar ik nog een beetje van geniet is dat mijn ongebruikte keuken er iedere dag onberispelijk uitziet door deze vorm van buitensporige verschraling val ik van lieverlee steeds vaker in herhaling

Och wat zou ik graag zitten met iets zwaars op de maag ook wacht ik nog op een gulle gever zodat ik iets heb voor op mijn lever mijn dieet is zelfs zo arm dat ik geen grip meer heb op mijn twaalfvingerige darm ik zou bij god niet weten wat er nog in me zit om op te vreten de laatste keer dat ik iets te bikken kon halen was vorige week toen ik er op bed over lag te malen kon ik de vrijheid van meningsuiting maar verliezen dan kreeg ik weer iets voor mijn kiezen ik kan er heel slecht tegen dat er weer niks op de schaal ligt voor afwegen voor de lege keukenkastjes denk ik elk etmaal weer had ik bij de gehaalde gram maar een onsje meer het enigste waar ik nog een beetje van geniet is dat mijn ongebruikte keuken er iedere dag onberispelijk uitziet door deze vorm van buitensporige verschraling val ik van lieverlee steeds vaker in herhaling

Zeg Bar en Boosman heb ik dit stukje nou al eerder gepub- liceerd of niet?

from  Kroeber

Kroeber

#002308 – 23 de Setembro de 2025

Em Portugal fica-se muito impressionado com a fúria com que a equipa nacional de rugby canta o hino, como se fossem personagens do 300, em emocionados berros de quem se prepara para a guerra. Eu, neste futuro próximo em que o Irão continua a ser bombardeado e a ripostar espalhando a guerra em volta, fiquei impressionado com uma atitude oposta, bem mais corajosa: a equipa feminina de futebol do Irão, durante a Taça Asiática, protestou contra o regime iraniano com silêncio, recusando-se a cantar o hino. Fala-se agora de que repercussões podem sofrer ao regressar ao Irão, algumas jogadoras pediram asilo político.

What’s On My Kobo Reader?

It’s nice to know that some of my readers have Kobo devices. In addition to my Kindle Paperwhite Gen 7, I also have a Kobo Clara HD. I love my Clara because it’s so easy to upload EPUBs on it.

I’m currently reading The Last Coyote by Michael Connelly. After watching the entire seasons of Bosch, Bosch Legacy, and Ballard, I started reading the books from the beginning. I know Connelly also has the Lincoln Lawyer series and some standalone stories, maybe I’ll read them.

But I do want to read all the Bosch and Ballard ones. I’m quite surprised how different the books are compared to the TV shows. Still, I’m entertained and I can’t stop reading them.

So, what books are you reading right now? Let me know and I might check them out.

#books #Ballard #Bosch #Kindle #Kobo #reading

from  Roscoe's Quick Notes

Roscoe's Quick Notes

Spurs vs. Celtics.

My game of choice tonight comes from the NBA, it will feature the Boston Celtics vs. my San Antonio Spurs. With its scheduled start time of 7:00 PM Central Time, this is as late a game as I dare watch during the work week. (No, I don't work anymore, but the wife does. And I need to be up early to fix her coffee and help her leave on time.) So it'll be necessary to have my night prayers caught up by game's end so I can turn in right away.

And the adventure continues.

Joakim

from Holmliafolk

Jeg har to tatoveringer. Den ene er på leggen. Det hender jeg glemmer den litt, for jeg ser den sjelden, men jeg vet den er der. Den dukket opp på en heisatur til Rhodos for tre år siden. I LOVE BEERSKIS, står det. Jeg elsker ølski. Det hender folk tror det skal være whiskey, men nei, det er ølski, stå på ski og drikke øl.

Den andre fikk jeg på min første guttetur ever, til Ayia Napa. En kompis tok og tatoverte inn bursdagen sin på håndleddet, og da måtte jeg gjøre det og. 02.03.1993 på det venstre håndleddet, på innsiden, rett over pulsåra.

Det var for femten år siden. Jeg var 18 år. I dag fyller jeg 33.

Daily Reminders

from  The Poet Sky

The Poet Sky

🩵 Take your meds 🩵 You are enough 🩵 You are a good in this world 🩵 You are worth it 🩵 Treat yourself 🩵 You matter 🩵 It's gonna be okay 🩵 Your feelings are valid 🩵 There is so much to love about you 🩵 Get some rest

Ray Bradbury, prophet

Ray Bradbury's 1957 book Dandelion Wine is a tale of small town Midwestern America through the eyes of a 12-year old boy. I picked it up after re-reading the more well-known Something Wicked This Way Comes, which comes after Dandelion Wine in the trilogy.

Yesterday, I read through the chapter on the 'Happiness Machine' that Leo Auffmann sets out to make. The idea hits him like a bolt of lightning, and he becomes obsessed on creating a machine that will bring people happiness. Interestingly, his wife (and others) don't see the need for such a device. After a frightening encounter with one of their children and the machine, Leo's wife Lena wants to try it out. Leo and the children hear her crying from outside the machine. Puzzled by the experience, here is Leo and Lena's conversation when she comes out:

“Oh, it's the saddest thing in the world!” she wailed. “I feel awful, terrible.” She climbed out through the door “First, there was Paris...” “What's wrong with Paris?” “I never even thought of being in Paris in my life. But now you got me thinking: Paris! So suddenly I want to be in Paris and I know I'm not!” “It's almost as good, this machine.” “No. Sitting in there, I knew. I thought, it's not real!” “Stop crying, Mama.” She looked at him with great dark wet eyes. “You had me dancing. We haven't danced in twenty years.” “I'll take you dancing tomorrow night!” “No, no! It's not important, it shouldn't be important. But your machine says it's important! So I believe! It'll be all right, Leo, after I cry some more.” “What else?” “What else? The machine says,'You're young.' I'm not. It lies, that Sadness Machine!” “Sad in what way?” His wife was quieter now. “Leo, the mistake you made is you forgot some hour, some day, we all got to climb out of that thing and go back to dirty dishes and the beds not made. While you're in that thing, sure, a sunset lasts forever almost, the air smells good, the temperature is fine. All the things you want to last, last. But outside, the children wait on lunch, the clothes need buttons. And then let's be frank, Leo, how long can you look at a sunset? Who wants a sunset to last? Who wants perfect temperature? Who wants air smelling good always? So after awhile, who would notice? Better, for a minute or two, a sunset. After that, let's have something else. People are like that, Leo. How could you forget?” “Did I?” “Sunsets we always liked because they only happen once and go away.” “But Lena, that's sad.” “No, if the sunset stayed and we got bored, that would be a real sadness. So two things you did you should never have. You made quick things go slow and stay around. You brought things faraway to our backyard where they don't belong, where they just tell you, 'No, you'll never travel, Lena Auffmann, Paris you'll never see! Rome you'll never visit.' But I always knew that, so why tell me?”

While reading this, I couldn't help but think, 'Bradbury prophesied smart phones and social media perfectly!' Lena's experience is the same as legions of others who report dissatisfaction and sadness with their own lives after being drawn in to the fake world of social media. The most poignant observation is, “It's not important, it shouldn't be important. But your machine says it's important! So I believe!”

Online (we don't see the term 'virtual reality' used often any longer) the relationships there aren't real. The experiences aren't real. The only thing seemingly real is the disappointment people face when they look at the reality of their lives against the false creations of Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and the like. While not as dystopian as Fahrenheit 451, Bradbury saw the bleak future that awaited humanity as we traded the real for the imaginary. He was a genius.

In the remainder of the chapter, the Happiness Machine bursts into flame, destroying itself and the Auffmann's garage. In the aftermath, Leo sits on his front porch looking in to his family going out their ordinary, day-to-day lives and has the epiphany, “There it is...the Happiness Machine.”

Brilliant. Thank you, Mr. Bradbury.

#Bradbury #culture #life #reading

Coding Is Dead, Long Live Programming

from Ian Cooper - Staccato Signals

Summary

In this post, we argue that the role of a coder now belongs to a coding agent, but that the distinct role of a programmer defines the software engineer's role in interacting with the agent to produce computer programs. At the heart of this are, I think, answers to questions we have about software maintenance and the education of junior engineers.

Coding is Dead

Commentators in the tech industry have recently declared that “coding is dead.” The triggers for this statement are:

- LLMs, whose transformer architecture excels at pattern recognition and translation, have achieved a high success rate on key coding tasks, particularly since the December 2025 model releases.

- The improvements in coding agents have pushed the success rate for the code that an LLM generates above the 80% threshold, where agents can begin the journey toward independently doing work without human review for short tasks and increasingly lengthening.

- A wider understanding of good practices in context engineering—using the file system as memory and aggressively managing context by creating fresh agents—has helped prevent the quality drop that comes from context rot.

- The improvement of techniques to capitalize on agents' relentlessness to get them to iterate toward high-quality outputs via clear acceptance criteria for “done-done,” avoiding low-quality output caused by reward hacking. See How To Ralph.

Of course, all statements like “coding is dead” are hyperbolic, but it would be foolish to refute that in 2026 and beyond: agents will write the majority of code.

If coding is dead or will be dead by the early 2030s, what will software engineers do?

Programming is not Coding

The terms programming and coding can seem interchangeable, but historically, they are not the same. They refer to different activities, but for many years we have performed them together, making the distinction unclear.

Following Yourdon and Constantine in Structured Design, we assert that software engineering has the following roles:

- Analyst: talks to the customer to elicit the requirements for what we want to automate.

- Designer: determines how to meet the requirements and required quality attributes of the software, for example, how we split into modules, how those interoperate, scale, provide transactional integrity, etc.

- Programmer: decides on the design of programs: algorithms, data structures, and design patterns – writes coding specifications. QA of the program.

- Coder: implements the program design and has knowledge of syntax.

In the latter two roles, the original distinction between programmer and coder stems from an era when code was often punched out on cards rather than encoded in a high-level language. A programmer handed the coder a coding specification that defined the program to be written:

“Each component subprogram is coded using the coding specifications. Ideally, this phase would be a simple mechanical translation; actually, detailed coding uncovers inconsistencies that require revisions in the coding specifications (and occasionally in the operational specifications).” Bennington, Herbert; Production of Large Computer Programs.

Once, in larger organizations, different people performed the roles of programmer and coder. The programmer specified what code was needed and handed the resulting coding specification to the coder, who then authored the code that was to be loaded into the computer.

With the introduction of high-level languages, it became easier for developers to perform both the programming and coding roles simultaneously. The compiler did much of the work that the coder had done before, so the program specification could be completed simultaneously with coding. Later, the RAD/agile movements leveraged the ease with which programs could be specified as code was written, speeding up software development by collapsing many steps into a single process and shifting quality left via Test-Driven Development.

It is because of high-level languages and RAD/agile practices that many people use “programming” and “coding” interchangeably. But they are not the same.

Coding or Programming: What is the Difference?

You can reason about this difference easily. Once you learn multiple programming languages, you come to appreciate that all of them have variations of the same concepts: control structures, variables, etc., that only differ by their syntax. By contrast, data structures and algorithms don't depend on specific language syntax. Object-Oriented models of your domain can be developed using CRC cards or UML, without writing code. We think of these concepts as existing outside the syntax and the code, at the level of the program. You can reason about a program in a conversation, or on a whiteboard, without needing to use a specific syntax.

When writing code, you probably used to look up what you needed in documentation or examples and translate it to your domain. These statements were code and reusable as such, once fitted to the logic of your program.

We often overestimate the importance of coding in this merger of roles. It is likely that you spend more of your time as a programmer debating which frameworks and libraries you want to use, and what classes and interfaces form part of your model, than you do over whether you should use a for or while loop.

Knowing what syntax to use in a particular language is the role of a Coder; knowing what the code should do is the role of the Programmer.

Alex Booker has a good description of the difference between coding and programming in his video Coding or Programming: What Is the Difference?

XP: Elaboration, CRC Cards, Programming & Coding

Armed with this understanding, it may be helpful to identify when a developer is in a programmer or coder role. Consider the roles we took in an XP-like software development life cycle (SDLC).

- A team takes a story from the backlog and discusses it with the product owner. They develop acceptance criteria. Engineers perform the analyst role.

- The team makes architecturally significant decisions; these may bubble outside the team. Engineers perform the role of the designer.

- Skills like Attribute-Driven Design and Large Scale Domain Driven Design are applied here.

- The team may write an ADR to record architectural decisions.

- The team discusses how to implement the story. They discuss key parts of the domain model, including finding actors, assigning responsibilities to roles, and mapping roles to classes. They talk about the suitability of data structures and algorithms. They perform the role of the programmer.

- As part of this process, the engineers may explore the space with tools like CRC cards.

- The team may write an ADR to record architectural decisions.

- Once the team has a design, they break it into tasks. They perform the role of the programmer.

- They take tasks one by one and pair or mob on them.

- One of the pair uses the keyboard to type code. They are in the coder role.

- One of the pair, or the rest of the mob, specifies what should be written, watches for errors, correlates with the design, and reviews. They are in the programmer role.

The developer roles are: analyst, designer, programmer, coder.

Notice how the coder role is a relatively small part once we break out programmer from it. Because any team member may switch in and out of roles, we overlook how often we are in the programmer role rather than the coder role (or the analyst or designerrole). This tallies with the observation that coding is a small part of what software engineers do and aligns with the reason: many activities are, in fact, programming rather than coding. Your perception of how little of your job is coding is not incorrect, but you perhaps don't appreciate that analysis, design, and programming are engineering activities.

The Middle Loop

In their book Vibe Coding, Steven Yegge and Gene Kim discuss the Middle Loop, the construction of the context the agent uses when carrying out tasks. We often call this specification-driven development, but it bears less resemblance to older document-heavy approaches to software development, and more to the activities of the classic XP loop, with agents in the coding role.

Whilst this is an evolving practice, we can think about a common loop for working with agents like this:

The Middle Loop

- A developer takes a story from the backlog and discusses it with the product owner. They develop acceptance criteria. Engineers perform the analyst role.

- The team may use a PRD to record the requirements.

- The agent may act in a researcher role. The developer may need to make architecturally significant decisions; these may bubble outside the team. The engineer performs the role of the designer.

- Skills like Attribute-Driven Design and Large Scale Domain Driven Design are applied here.

- The agent may act in a researcher role.

- The developer may write an ADR to record architectural decisions.

- The developer decides how to implement the story.

- As part of this process, the engineer and agent explore the space.

- The agent may act in a researcher role.

- The developer performs the programmer role, making decisions with discretion and taste.

They look at key parts of the domain model, finding actors and responsibilities, assigning responsibilities to roles, and roles to classes.

- They talk about the suitability of data structures and algorithms.

- They might use tools like Responsibility Driven Design (RDD).

- As part of this process, the engineer and agent explore the space.

- Once the developer has a design, the agent breaks it into tasks. The developer reviews the tasks, performing the role of the programmer.

The Inner Loop

- The agent takes tasks one by one.

- The agent writes the code. They are in the coder role. The developer watches for errors, correlates them with the design, and reviews. They are in the programmer role.

The Inner Loop The Middle Loop

The developer roles are: analyst, designer, programmer. The agent roles: researcher, coder

The loop is fundamentally the same as XP, but the developer no longer performs the coder role and may be assisted by a researcher role:

The researcher role helps us utilize existing knowledge and patterns more efficiently because the programmer can delegate research that they used to do to the agent.

We didn't previously break out this role; it was part of being a programmer, and it is what we were doing when we visited Stack Overflow, documentation, or pulled candidate objects from the requirements based on their responsibilities.

We might still need to do some of this by reading, but the agent can help with heavy lifting, so we add a new role for that. However, decision-making, based on discernment and taste, lies with the programmer role.

The key, though, is that much is familiar from our first loop. Even with an agent's help, many roles still fall to the human-in-the-loop.

High-Level Direction Judgement and Taste

“It’s not perfect, it needs high-level direction, judgement, taste, oversight, iteration and hints and ideas. It works a lot better in some scenarios than others (e.g. especially for tasks that are well-specified and where you can verify/test functionality). The key is to build intuition to decompose the task just right to hand off the parts that work and help out around the edges.” Andrej Karpathy, x.com

Judgement, taste, etc., are the programmer's responsibilities. The agent is good at coding, but it needs help deciding what to write. That is why we still need the programmer role and don't simply delegate that to the agent. Maybe one day it will do that role too, but that day is not today.

Watch the Loop

Why suggest that the programmer/coder split is like pair/mob programming, where one partner watches the other? Because the agent needs to be observed.

“It's important to watch the loop as that is where your personal development and learning will come from. When you see a failure domain, put on your engineering hat and resolve the problem so it never happens again.

In practice this means doing the loop manually via prompting or via automation with a pause that involves having to press CTRL+C to progress onto the next task. This is still ralphing as ralph is about getting the most out how the underlying models work through context engineering and that pattern is GENERIC and can be used for ALL TASKS.” Geoffrey Huntley, Everything is a Ralph Loop

Now, some argue that it is inefficient. Do you need to review the agent's output? It's just coding. Just use a linter and check that it passes the tests.

Watching the loop confirms the theory behind what you are doing. What is the theory? That's the bit you must come away from the development loop with. It is how you will be able to reason about and maintain the software.

Programming as Theory Building

Peter Naur's essay, “Programming as Theory Building” states that the most important part of programming is theory building: “ On the Theory Building View of programming the theory built by the programmers has primacy over such other products as program texts, user documentation, and additional documentation such as specifications.” The theory, the knowledge built up by the programmer in crafting the program, is important for three reasons:

- The programmer can explain how the program maps to the problem domain: “the programmer must be able to explain, for each part of the program text and for each of its overall structural characteristics, what aspect or activity of the world is matched by it.”

- The programmer can explain the decisions that led to the choices expressed in the program text and documentation.

- The programmer is able to understand how to modify the program to support change: “Designing how a modification is best incorporated into an established program depends on the perception of the similarity of the new demand with the operational facilities already built into the program.”

It is the latter point that is key. In large codebases, our ability to maintain a program depends on our possessing the theory of the program. The theory lets you modify the program successfully because you understand how the program's theory should be adjusted to meet the new requirement.

“The point is that the kind of similarity that has to be recognized is accessible to the human beings who possess the theory of the program, although entirely outside the reach of what can be determined by rules, since even the criteria on which to judge it cannot be formulated.”

The risk is that modifications made to a program, without understanding the theory, lead to decay. Most of us have experienced decay when modifications accrete as new additions that don't fit the theory of the remainder of the program. Eventually, the program becomes incoherent, and we are forced to rewrite.

“The death of a program happens when the programmer team possessing its theory is dissolved. A dead program may continue to be used for execution in a computer and to produce useful results. The actual state of death becomes visible when demands for modifications of the program cannot be intelligently answered. Revival of a program is the rebuilding of its theory by a new programmer team.”

Theory is the key to maintenance. If you don't have the theory, then you will struggle to maintain the software, because you will struggle with the programmer role.

“A very important consequence of the Theory Building View is that program revival, that is, reestablishing the theory of a program merely from the documentation, is strictly impossible.”

Code Reviews and Theory Building

In teams that don't use pair programming, a common compensation is to do code reviews. The purpose of both pair programming and code review extends beyond quality review; it is about sharing the theory of the program.

Often, teams struggle with reviews as flashpoints or have arguments in pairing because they fail to do enough theory-building when they pull the story from the backlog, a process we call elaboration or alignment. A simple way for many teams to improve code reviews is to avoid doing design there but to shift it left into elaboration when the story is pulled from the backlog. This shifts the theory building to an earlier step. The review then just confirms that the code matches the theory. Conflict arises when the theory is unclear during pairing or review.

Pair programming and code reviews spread the theory through the team. Junior developers often don't have the same facility with theory-building that senior developers do. Pairing, or code reviews, allow developers to exchange the theory through conversation and reach alignment.

These exchanges work best when they don't focus on the code but on the theory of the program.

The danger is that a new developer on the team, who has yet to build the theory for the program, in conversation with other developers, correctly specifies the program without the theory. Without the theory, their programming specification is likely to be wrong, and the resulting code will be wrong.

InnerSource, OpenSource, and Theory Building

OpenSource, or InnerSource projects, encounter this need to help contributors acquire theory all the time. Often, Open-source projects identify tasks that require less theory to help new contributors get started. Once contributors establish a track record of contributions, maintainers begin to invest the time in helping them understand the theory.

LLMs and Theory Building

The LLM cannot be used in the analyst, designer, or programmer roles, only as a researcher to support, because it cannot capture the theory of the program as expressed by Naur.

- The LLM does not have the context that lives outside the code, docs, and ADRs.

- The theory cannot be reconstructed only from the artifacts in the git repository [Naur].

- The LLM struggles with large programs. They remain too large for it to hold it all in the conversation and avoid context rot.

As such, an agent struggles to know the theory of the program and fulfill the programmer role. This is why the design is a conversation with the agent. This is why the loop must be observed. Acting as the programmer, you are building the theory of the program.

This, then, is the danger of handing the programmer role to the agent, rather than using it as a researcher. You no longer have the theory of the program, which will lead to the software decaying under modification.

This is why, when working with an agent, it is important to observe the loop, because we need to build the theory of the program. We may choose to work either as a pair programmer, reviewing the test and implementation as they are developed, or as a code reviewer, looking at the PR from the agent. Again, both will be easier if we shift left and put more effort into the design of our program, building a clear theory.