Want to join in? Respond to our weekly writing prompts, open to everyone.

Tuesday

from  Roscoe's Story

Roscoe's Story

In Summary: * Happy that my Texas Rangers won their game against the Chicago Cubs this afternoon. Somewhat apprehensive about the storms that are supposed to hit us later tonight then continuing through tomorrow morning. Lord knows we need the rain, but we can do without the hail and high winds. I do take some consolation in the weather maps showing the heaviest weather hitting counties to the West and North of us, then sliding away from us to the North and East.

Prayers, etc.: * I have a daily prayer regimen I try to follow throughout the day from early morning, as soon as I roll out of bed, until head hits pillow at night. Details of that regimen are linked to my link tree, which is linked to my profile page here.

Starting Ash Wednesday, 2026, I've added this daily prayer as part of the Prayer Crusade Preceding the 2026 SSPX Episcopal Consecrations.

Health Metrics: * bw= 230.49 lbs. * bp= 150/88 (66)

Exercise: * morning stretches, balance exercises, kegel pelvic floor exercises, half squats, calf raises, wall push-ups

Diet: * 06:15 – 1 ham & cheese sandwich * 07:15 – 2 crispy oatmeal cookies * 09:50 – air-popped popcorn * 12:15 – biscuit & jam, hash browns, sausage, scrambled eggs, pancakes * 14:50 – home made meat & vegetable soup, fresh mango

Activities, Chores, etc.: * 05:00 – listen to local news talk radio * 05:45 – bank accounts activity monitored * 06:00 – read, write, pray, follow news reports from various sources, surf the socials, and nap * 13:20 – watching MLB Spring Training Game on MLB+, Toronto Blue Jays, vs. Atlanta Braves * 15:05 – now following two MLB Spring Training Games: 1.) Diamond Backs and Dodgers, live video and audio on MLB TV, and 2.) Cubs and Rangers, live scores and stats on MLB Gameday screen * 17:17 – and the Rangers beat the Cubs 8 to 3. Go Rangers! (Don't know what happened to the D'Backs and Dodgers. I lost their feed in early innings and never got it back.) * 18:00 – tuned into 1200 WOAI, the flagship station for the San Antonio Spurs, for pregame coverage then the call of tonight's game vs. the Boston Celtics.

Chess: * 14:00 – moved in all pending CC games

A direita portuguesa vem buscar os nossos corpos

from  Kuir - cultura e inspiração Cuir

Kuir - cultura e inspiração Cuir

A repatologização como projecto político: quando a direita se une contra a autodeterminação.

No dia 19 de março, a Assembleia da República vai decidir se Portugal continua a reconhecer que as pessoas trans existem sem pedir licença à medicina.

No próximo dia 19 de março, três partidos da direita portuguesa — Chega, PSD e CDS-PP — vão levar à Assembleia da República projectos de lei cujo objectivo é um só: desmantelar a Lei n.º 38/2018, que consagra o direito à autodeterminação da identidade de género. Não são três iniciativas independentes. É uma ofensiva coordenada contra a existência jurídica das pessoas trans em Portugal. E é preciso chamá-la pelo nome.

Bandeira Trans – Identidade e Direito. A luta pela autodeterminação de género em Portugal enfrenta uma nova ofensiva parlamentar. | Fotografia de Lena Balk (2020) – Uso gratuito sob a Licença da Unsplash

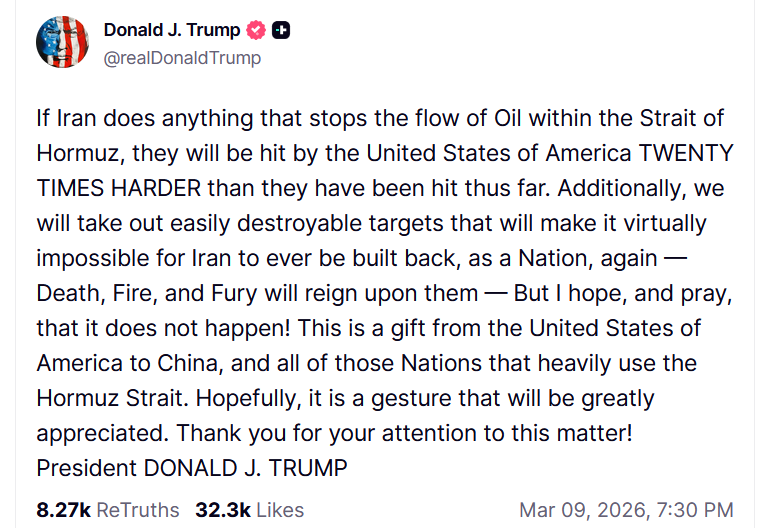

O Chega quer a revogação pura e simples da lei e o regresso a um modelo de diagnóstico clínico obrigatório. O PSD, pela mão de Hugo Soares — o mesmo que em 2015 propôs um referendo sobre a adopção por casais homossexuais e que, dias antes deste debate, não hesitou em invocar cinicamente os direitos das minorias e das mulheres para justificar o apoio cobarde de Portugal ao ataque dos EUA ao Irão —, apresenta um projecto que restaura o regime da Lei n.º 7/2011, devolvendo a profissionais de saúde o poder de decidir quem pode ou não alterar a menção do sexo no registo civil.

Entre as Lajes e a Lei 38: A Hipocrisia Homonacionalista de Hugo Soares

Um exemplo claro de retórica homonacionalista, onde Hugo Soares (PSD) invoca a proteção de mulheres e minorias no Irão para legitimar o apoio militar aos EUA , contrastando com a ofensiva contra a autodeterminação de género em Portugal agendada para 19 de março.

Extrato da Reunião Plenária de 4 de março de 2026. Intervenção: Hugo Soares (PSD) sobre o apoio logístico aos EUA e a condenação do regime iraniano em nome das mulheres e minorias. | Duração do corte: 23 segundos (De 00:27:24 — 00:27:47). | Fonte Original: Canal Parlamento – Reunião Plenária de 04/03/2026

A hipocrisia é cirúrgica: os direitos das minorias servem para justificar uma guerra, mas não para proteger pessoas trans em Portugal. O CDS-PP, por sua vez, quer proibir a prescrição de bloqueadores hormonais a menores de 18 anos em contexto de incongruência de género. Três projectos, um só gesto: retirar às pessoas trans o direito de se nomearem a si mesmas.

Sejamos precisos. A alteração da menção do sexo no registo civil é um acto administrativo. Não implica cirurgias. Não implica tratamentos hormonais. Não implica qualquer procedimento médico. É papel. É reconhecimento jurídico. E é exactamente isso que a direita quer condicionar. A confusão deliberada entre reconhecimento legal e intervenção clínica é a grande mentira desta ofensiva. Quem a repete sabe o que está a fazer.

Reintroduzir a exigência de diagnóstico clínico significa, na prática, obrigar pessoas trans a provar perante um painel de especialistas que a sua identidade é real. Significa devolver ao poder médico a capacidade de validar ou recusar a existência jurídica de alguém. Paul B. Preciado chamou a isto farmacopolítica: o Estado como regulador dos corpos dissidentes, distribuindo ou negando o acesso à identidade conforme critérios que não são científicos — são disciplinares. Judith Butler, há mais de três décadas, demonstrou que o género não é uma essência que a medicina possa certificar — é uma construção performativa que o poder reitera ou pune. Exigir um diagnóstico é precisamente reiterar a ficção de um género verdadeiro, acessível apenas por validação institucional.

A ciência fala contra a direita. E fala em português. A Sociedade Portuguesa de Sexologia Clínica emitiu um parecer técnico-científico sobre o projecto do Chega que não deixa margem para dúvidas: a iniciativa assenta em premissas que contradizem o consenso clínico internacional. Chamar ideologia à disforia de género, como faz o Chega, é negacionismo científico. A Organização Mundial de Saúde retirou a incongruência de género da categoria de perturbações mentais na CID-11. O parecer da SPSC vai mais longe e recorda que as dificuldades de saúde mental observadas em pessoas trans estão associadas ao estigma social e ao minority stress — não à identidade de género em si. Traduzindo: o problema não é ser trans. O problema é o que a sociedade faz a quem é trans. Legislar para aumentar o estigma é legislar para aumentar o sofrimento. Quem apresenta estes projectos de lei sabe-o — e fá-lo na mesma, porque o sofrimento das pessoas trans é rentável eleitoralmente.

Há um silêncio na proposta do PSD que merece ser nomeado. O projecto não faz qualquer referência às protecções relativas a pessoas intersexo menores de idade previstas na lei actual. A Lei n.º 38/2018 estabelece que, salvo risco comprovado para a saúde, intervenções cirúrgicas ou farmacológicas que modifiquem as características sexuais de menores intersexo não devem ser realizadas até que a pessoa possa manifestar a sua identidade de género. O PSD apaga esta disposição. O silêncio institucional sobre os corpos intersexo é sempre cúmplice da violência cirúrgica exercida sobre crianças cujos corpos não cabem na norma binária. Omitir não é esquecer. É autorizar.

Nada disto acontece no vazio. O relatório anual da ILGA-Europe de 2026 é categórico: a Europa entrou numa nova fase de regressão democrática. O que antes eram ataques pontuais contra pessoas LGBTI+ é agora política estruturada — limitação de direitos, criminalização, silenciamento. A Geórgia equipara relações homossexuais ao incesto. A Rússia classifica o movimento LGBTI+ como extremista. O Reino Unido redefine legalmente o conceito de mulher com base no sexo biológico. A administração Trump revoga protecções contra a discriminação de pessoas trans. É nesta companhia que a direita portuguesa quer colocar o país.

Mas há uma contra-corrente — e a direita portuguesa está do lado errado dela. Em fevereiro de 2026, o Parlamento Europeu aprovou uma resolução que recomenda o reconhecimento pleno das mulheres trans como mulheres, considerando a sua inclusão essencial para a eficácia das políticas de igualdade de género: 340 votos a favor, 141 contra, 68 abstenções. A extrema-direita e os conservadores ficaram em minoria. A resolução abrange ainda a protecção mais ampla de todas as pessoas LGBTIQ+, exigindo que a UE assuma a liderança na luta contra os movimentos antigénero. A Comissão Europeia lançou uma nova estratégia de igualdade LGBTIQ+ para 2026-2030 que nomeia explicitamente mulheres e homens trans. Enquanto a Europa institucional reconhece, a direita portuguesa quer revogar. Enquanto o Parlamento Europeu vota pela dignidade, o parlamento português agenda o retrocesso.

Do lado esquerdo do hemiciclo, o Bloco de Esquerda apresentou, pela mão de Fabian Figueiredo, um projecto que visa reforçar a aplicação da Lei n.º 38/2018 — orientações para escolas, formação para profissionais, mecanismos de apoio a estudantes trans. É necessário. Mas não basta. Dean Spade tem argumentado que os sistemas administrativos de classificação de género são, por natureza, mecanismos de controlo — e que a luta pela autodeterminação não se ganha apenas nos parlamentos. Ganha-se nas ruas, nas escolas, nos locais de trabalho, em cada espaço onde um corpo dissidente é forçado a justificar a sua existência.

O debate de 19 de março não é sobre procedimentos administrativos. É sobre quem tem o poder de definir quem somos. A direita portuguesa, colada numa ofensiva que vai de Budapeste a Washington, quer devolver esse poder ao Estado, à medicina e à norma. A nossa resposta é a mesma de sempre: os nossos corpos, a nossa palavra e a recusa absoluta de pedir licença para existir.

Projeto de Lei do Chega (CH): Objetivo: Revogação total da lei atual e regresso ao modelo de diagnóstico clínico obrigatório. Link/Referência: Projeto de Lei n.º 391/XVI/1.ª – Revogação da Lei n.º 38/2018.2.

Projeto de Lei do PSDObjetivo: Restaurar o regime da Lei n.º 7/2011, exigindo que profissionais de saúde validem a alteração do sexo no registo civil. O artigo nota ainda que este projeto omite as proteções para pessoas intersexo.Link/Referência: Projeto de lei n.º 486/XVII/1ª – Alteração ao regime jurídico da identidade de género.

Projeto de Lei do CDS-PPObjetivo: Proibir a prescrição de bloqueadores hormonais a menores de 18 anos em contexto de incongruência de género.Link/Referência: Projeto de Lei n.º 479/XVI/1.ª – Proteção de menores em cuidados de saúde de género.

#cuir #kuir #trans #autodeterminação #lei38 #direitostrans #portugal #assembleia #repatologização #SPSC #intersexo #LGBTI #feminismo #descolonial

the quiet mercy of unanswered prayers

from Douglas Vandergraph

There is a kind of prayer that only emerges after time has softened the sharp edges of memory. It is not the prayer we pray when we are desperate for something to happen, when our hands are clenched and our hearts are racing and our words come out hurried and breathless because we believe that if God would just give us this one thing, everything would finally fall into place. Those prayers are honest and sincere, but they are still shaped by the limited vision of a human heart that can only see the next few steps of the road ahead. The prayer I find myself praying now is different. It is slower. It is quieter. It carries the weight of years and the humility that comes from realizing how many times I was absolutely convinced I knew what I needed, only to discover later that what I wanted would have led me somewhere far less beautiful than where God ultimately guided me. So this prayer begins with gratitude, not for the things that came easily, but for the things that never arrived at all. Thank you, God, for protecting me from what I thought I wanted.

When we are young in faith, and sometimes even when we have walked with God for decades, we tend to interpret silence as absence and closed doors as rejection. We bring our requests before heaven with the quiet assumption that the best possible outcome is the one that matches our plans. We imagine the job that would make everything better, the relationship that would complete our lives, the opportunity that would finally place us on the path we believe we were meant to walk. And when those things do not come, the human heart often moves through a season of confusion. We wonder if we prayed incorrectly, if we were overlooked, if somehow the door remained closed because we were not worthy enough to step through it. Yet time has a way of revealing something far more profound than the immediate answer we were seeking. Time slowly teaches us that God's no is not rejection. It is protection.

I look back now at moments that once felt like disappointment and realize they were quiet acts of mercy. There were relationships I begged for that would have anchored my heart to people who were not meant to walk beside me for the long journey. At the time, those losses felt devastating because the human heart does not easily release something it has already imagined building a life around. But now, with distance and perspective, I see what God could see all along. I see the conflicts that would have grown, the misaligned values that would have slowly worn down the soul, the compromises that would have quietly pulled me away from the person I was meant to become. The door closed not because love was denied, but because a deeper kind of love was protecting me from a future that would have slowly eroded the peace God intended for my life.

There were also opportunities I chased with everything I had. I remember praying for certain paths to open with a level of certainty that felt almost unshakable. In those moments I was convinced that if God allowed that one opportunity to unfold, it would validate every effort I had poured into reaching it. Yet the opportunity never came, and for a while the absence of that breakthrough felt like failure. It is humbling to admit how long it sometimes takes to recognize the wisdom of divine restraint. Only later did I begin to notice the unseen redirections that followed those disappointments. Because the path that closed forced me to explore a different road, and that road slowly became the place where my voice, my purpose, and my calling began to take shape in ways I could never have predicted when I first asked for something else entirely.

One of the quiet truths of faith is that God's guidance often appears in the form of absence rather than presence. We tend to celebrate the doors that open, the breakthroughs that arrive, and the moments when our prayers seem to unfold exactly as we hoped. Those are beautiful moments and they deserve gratitude. But there is another category of divine work that rarely receives the same recognition. It is the silent intervention that prevents us from stepping into situations that would have drained our spirit, confused our direction, or slowly led us away from the life God designed for us. Those interventions rarely announce themselves with thunder. Instead they appear as delays, detours, unanswered emails, unexpected changes, and circumstances that shift just enough to redirect our steps.

In the middle of those experiences it is easy to feel frustrated. The human mind is wired to search for control and clarity, and when life refuses to follow the outline we carefully constructed, the uncertainty can feel unsettling. Yet faith invites us to consider the possibility that the unseen wisdom of God is operating far beyond the horizon of our immediate understanding. What appears to us as a delay may actually be a timing adjustment designed to align our lives with people and opportunities that have not yet arrived. What appears to us as a closed door may actually be the gentle hand of God steering us away from something that would have entangled us in unnecessary hardship.

I think about the prayers I prayed years ago, and I sometimes smile at the confidence I carried into those conversations with God. I truly believed I knew what would make my life complete. I imagined that if certain relationships had survived, if certain plans had succeeded, if certain dreams had unfolded exactly as I envisioned them, everything would have aligned perfectly. Yet standing where I am now, I can see how fragile those imagined futures really were. They were built on partial understanding, incomplete information, and emotional impulses that had not yet been refined by experience. God, in His patience, allowed me to feel the sincerity of those prayers without granting the outcomes that would have trapped me inside them.

There is a moment in every believer's life when gratitude begins to expand beyond answered prayers and into a deeper appreciation for the prayers that never materialized. That shift does not happen overnight. It grows slowly as we observe the way our lives unfold over time. We begin to notice the people who eventually entered our story, the opportunities that emerged from unexpected directions, and the ways our character matured through seasons that initially felt like loss. With enough distance, those once painful disappointments begin to reveal themselves as quiet turning points that protected our future.

The truth is that God sees connections we cannot see. He understands the ripple effects of decisions that have not yet happened and the unseen consequences of paths we are eager to walk. When we pray for something, we are often focusing on the immediate benefit we imagine it will bring. God, however, is considering the full arc of our life. He is thinking about who we are becoming, the influence we will carry, the people we will impact, and the spiritual depth that will shape the way we move through the world. When a request conflicts with that larger vision, the most loving answer God can give is no.

That kind of love can be difficult to recognize in the moment because it does not always feel comforting at first. It feels like confusion. It feels like waiting. It feels like watching something slip through your fingers that you were certain belonged in your future. But over time the wisdom of divine restraint begins to emerge. The very thing we once believed would complete our happiness reveals itself as something that would have limited our growth or redirected our lives away from the deeper purpose God was preparing.

Faith matures when we begin to trust not only the yes of God but also the no. We learn to believe that every response from heaven carries intention, even when that intention is not immediately clear. The story of Scripture reminds us repeatedly that God's plans unfold across timelines far longer than our own expectations. Abraham waited decades for promises to materialize. Joseph endured years of hardship before the purpose of his journey became visible. The disciples themselves often misunderstood the path Jesus was walking until the resurrection revealed what had been unfolding all along.

These stories remind us that God's perspective stretches across generations while ours often focuses on the next few months or years. The no we receive today may be protecting us from something we would only understand years later. The door that closes today may be guiding us toward a different environment where our gifts will flourish in ways we never anticipated. When we begin to see life through that lens, our prayers shift from demands into conversations filled with trust.

As the years move forward, something remarkable begins to happen inside the human heart that has walked with God through both answered and unanswered prayers. The heart begins to recognize patterns that were invisible before. What once looked like random disappointment begins to reveal itself as careful direction. Moments that seemed confusing begin to line up like quiet markers along a path that was being shaped long before we understood where it was leading. When I look back across my life now, I no longer see a collection of things that did not work out. I see a series of divine interventions that protected my future long before I had the wisdom to recognize what I was being protected from.

There were seasons when I prayed with absolute conviction that something needed to happen. I believed certain relationships were meant to continue. I believed certain doors needed to open. I believed certain answers needed to arrive quickly because the urgency in my heart felt overwhelming. In those moments, the silence of heaven felt almost confusing because my request felt sincere and heartfelt. Yet the passage of time revealed something that could never have been understood in the moment of asking. Those requests, if granted, would have altered the direction of my life in ways that would have quietly led me away from the deeper calling God had prepared.

It is humbling to admit how often we measure blessing by immediate satisfaction rather than long-term alignment with God's purpose. The human heart tends to interpret fulfillment through the lens of comfort, validation, and emotional relief. We imagine that the right relationship will finally quiet our loneliness, that the right opportunity will finally prove our worth, and that the right answer will finally remove the uncertainty that makes life feel unpredictable. But God measures fulfillment differently. He measures it through the lens of transformation, growth, character, and the quiet shaping of a soul that is learning how to trust Him beyond what can be immediately understood.

When I reflect on the doors that never opened, I realize that many of them would have placed me in environments that looked promising on the surface but carried hidden tensions beneath them. Some would have surrounded me with influences that slowly diluted the voice God was shaping inside my life. Others would have tied my future to circumstances that were never meant to sustain the kind of purpose God had written into my heart. At the time, I could not see those things. I could only see what I thought I wanted. Yet God's wisdom was already working beyond the horizon of my understanding.

There is something profoundly comforting about realizing that God's protection does not always arrive in dramatic form. Sometimes it comes through the quiet closing of a door that we tried desperately to open. Sometimes it appears in the form of a delay that forces us to grow into the person we will eventually need to be. Sometimes it arrives through the gradual dissolving of plans that once seemed perfect but were never meant to carry the full weight of our future. In each of those moments, what looks like disappointment is actually divine guidance gently redirecting our steps.

One of the most beautiful transformations in the life of faith occurs when gratitude expands to include the things that never happened. That kind of gratitude does not emerge from denial or forced optimism. It grows naturally from the realization that God's vision for our lives is broader and wiser than our immediate desires. When we begin to recognize how many unseen dangers we were quietly steered away from, our perspective begins to shift. The unanswered prayers that once felt painful become reminders that we were never navigating life alone.

There is a deep peace that settles into the soul when we understand that God's no is not the end of the story. It is simply the redirection of the path. What we thought we were losing was often the doorway to something far greater than we could have imagined at the time. That greater path does not always reveal itself immediately. Sometimes it unfolds slowly, step by step, as God shapes our character and prepares our hearts for the opportunities that will eventually appear.

Looking back now, I can see how many moments of protection were woven quietly into the story of my life. There were relationships that ended before they could turn into lifelong entanglements that would have drained the joy from my spirit. There were opportunities that slipped away just before they could pull my focus away from the calling that was slowly emerging inside me. There were delays that forced me to develop patience, humility, and resilience that I would later rely on when the path became more demanding.

At the time, none of those moments felt like protection. They felt like confusion, uncertainty, and sometimes even heartbreak. Yet the wisdom of time reveals what emotion could not see. Each of those moments was a quiet act of mercy. Each closed door was a hand gently guiding my life away from something that would have led me somewhere far less fulfilling than where God ultimately brought me.

Faith deepens when we begin to trust not only what God gives but also what God withholds. We start to realize that divine love operates with a level of foresight that we simply do not possess. While we are asking for what we think will make us happy today, God is shaping a life that will sustain meaning, purpose, and spiritual depth for decades to come. The things we thought we needed immediately were often distractions from the path that would eventually lead us toward something much more meaningful.

The prayer of gratitude that rises from this realization carries a different tone than the urgent prayers we once prayed. It is quieter and more reflective. It acknowledges that the journey has been guided even when we did not recognize the guidance at the time. It thanks God not only for the blessings that arrived but also for the dangers that were quietly avoided. It recognizes that protection often looks like loss in the moment but reveals itself as mercy when seen through the lens of time.

So this prayer becomes deeply personal. Thank you, God, for the relationships that did not last because they were never meant to shape the rest of my life. Thank you for the opportunities that slipped away because they would have pulled me away from the work you were preparing inside me. Thank you for the plans that collapsed because they were built on assumptions that could not carry the weight of the future you were designing. Thank you for the delays that forced me to slow down, reflect, and grow into the person who would one day recognize the wisdom of your timing.

There is a quiet confidence that grows in the heart when we begin to see life this way. It does not mean that disappointment disappears entirely. It simply means that disappointment no longer has the power to shake our trust in God's guidance. We begin to understand that every season carries purpose, even when that purpose is not immediately visible. The delays, the detours, the unexpected turns in the road all become part of a larger story that God is unfolding with patience and care.

When someone asks why something did not work out the way they hoped, I often think about how many times that same question lived inside my own heart. I remember the moments when I wished certain outcomes had been different. But standing where I am now, I realize that many of those outcomes would have quietly led me away from the life God intended for me to live. The things I thought I lost were actually the things that cleared the path for something better to appear later.

This understanding changes the way we pray. Instead of approaching God with the assumption that we already know the best possible outcome, we begin to pray with a deeper openness. We bring our hopes honestly before Him, but we also acknowledge that His vision extends far beyond our own. We trust that every response carries wisdom, even when that wisdom takes time to reveal itself.

The longer I walk through life with that perspective, the more I realize that the greatest blessings are often the ones that arrive after we release our insistence on controlling the outcome. When we loosen our grip on the specific form we believe our future must take, we create space for God to reveal possibilities we never considered. Those possibilities often lead to experiences, relationships, and opportunities that are far richer than the ones we once believed we needed.

So this message, this reflection, this prayer between a human heart and the God who has guided it through years of both clarity and confusion, ends with gratitude that is deeper than it once was. Not because life unfolded exactly the way I expected, but because it did not. The very things I once believed would define my happiness were quietly removed from my path so that something better could take their place.

Thank you, God, for protecting me from what I thought I wanted. Thank you for every closed door that kept me from stepping into a future that would have limited the person you were shaping me to become. Thank you for every delay that forced me to grow in patience, humility, and trust. Thank you for every unanswered prayer that quietly redirected my steps toward something more meaningful than I could have imagined at the time.

And if there is someone reading these words right now who is wondering why something in their life did not work out the way they hoped, I want them to understand something that took me years to fully grasp. God's silence is not abandonment. His no is not rejection. His delays are not indifference. They are often the quiet movements of a loving Father guiding your life away from something that would have limited your future and toward something that will one day make perfect sense.

The story you are living is still unfolding. The doors that closed behind you may have been protecting a path you have not yet discovered. And one day, when enough time has passed for the larger picture to come into focus, you may find yourself praying the same prayer I am praying now.

Your friend, Douglas Vandergraph

Thank you, God, for the things that never happened.

Watch Douglas Vandergraph’s inspiring faith-based videos on YouTube https://www.youtube.com/@douglasvandergraph

Support the ministry by buying Douglas a coffee https://www.buymeacoffee.com/douglasvandergraph

Financial support to help keep this Ministry active daily can be mailed to:

Vandergraph Po Box 271154 Fort Collins, Colorado 80527

Wearing a mask

from  Reflections

Reflections

from folgepaula

06:30 alarm rings, time to wake up, I should take a shower, Livi it's all good baby, sleep a bit longer, towel, shower, why is it not heating up? fuck I turned off the flat heating and the water heating all together oh no check the control, test one. Nothing. Test two. Damn whatever, today is nordic cold shower day, let me check it after work. Damn its cold, its cold and my throat is hurting, you can do this Paula, you can do this, hold your breath, ok enough, where's the blowdryer, oh here it is, it's 7h00, let me dry just the scalp, ok. Good. The rest can dry by itself. Sun protector. Brush my teeth. Vitamin B12. Vitamin D. A glass of water. Cooome Livi! Let's go gassi, Livi! Slowly. Schau, Livi! Our friend crow! Hi, crow! How are you doing? Livi nonono, don't scare the crow, it's our friend, schatzi. Da, komm her! Nice, a pee, maybe another one? Great and potty? Super, Livi! Yaaay! Let's go back to have breakfast! Press D. Let's wash these paws? Hop Hop, bathtube. Bravo. Livi, Friss schön, Schatzi! Hmmm nhami. Super. Now let's wash the bowl, and change the clothes where's my beanie? Here it is. Livi, mom will go to work but she will be back soon ok? We will go out again. Go to bed. Bye, love you. Press E. The bike padlock. the key, thekeythekey here it is, nice. Helmet, Youtube > Leif Vollebekk in Kate Bush cover? wow, nice. What a beautiful day. Why are people bringing their 5 yo kids to the city bike lane? Are they crazy? Up to Maria Hilfe, nice, Kirchengasse, bring the bike up, office key, park the bike, laptop laptop, connect, display, two screens, nice. Email 1, email 2, email 3, teams chat, city light posters from Germany are missing the Spring campaign signature, no, it's not according to the guideline, could we change it please? ok, you focus on production with graphic designer, we'll contact the printer to check for reprint. Hi, good morning! Yes, fine, let's grab a coffee. Email 4, email 5, yes, to ingest it in the platform you need to save it as csv., no, this is an excel, fine, send it over, there you go, you can ingest it now, email 6, email 7, hey everyone, kind reminder could you please update the strategy function slides, our preview is today at 3PM, yes leadership is invited, yes, I'll present it, here's the last year campaign from 2025 review for comparison, slides 8, 11 and 13 please. thanks, great, merch check, ecommerce check, content check, paid media, owned media, PR, performance media check, email 8, email 9, email 10, brief for Spotify, radio spot, ok. Good, folks, I am going home, yeah tomorrow I am here. Okay, byeee. Take the bike, press E, cycle cycle cycle, press D. Hi Liiiivi, hi cutie, I missed you. Just one more call and we go out together ok? Done. Let's go, livi? GASSI? Who wants to go gassi? Yaaaaay! Hi, danke, yes, she's very sweet, no, it's not an afghani, yes, she's 4 years old now, Mädchen, ja, danke, Du bist auch schön, danke, rerere, Tschüss!! Let's go back, Livi, it's dinner time, yaaay, there you go, wash the paws again, super, now insect food nhami, ok, I will go back soon, Livi. Mom needs to buy something to eat. Billa or Spar Billa or Spar? Fuck it, Billa. Avocado. Rice cookies. Tofu. Barista oat milk. Banana. Hmmm, what else, ah whatever. Next time. Mit karte bitte, paaaast, danke, Tschüss! walk walk. press D. FUCK IT THIS LIFT IS STUCK AGAIN ARE YOU KIDDING ME. Ring the alarm. Hi. Yes. I'm stuck in the lift. Could you please send the assistance? Please be fast, please, thank you. I will wait. I mean, I can only wait. HAHAHAHA THAT'S FUCKING UNBELIEVABLE. Let's watch a video, 5 minutes, 10 minutes, 15 minutes, 20 minutes, HI, yes, I'm here, ok, yes, I can hear you. The control is on the first floor, ok, I'll wait, Hi, oh, thanks, this lift is always a struggle, thanks so much, saved my day. Hi Livi, I'm back, let me take a shower, will cuddle you soon. AH no, the heating. ok, Valliant manual, pump check all good, Gebläse check, hmm still on 0, maybe it's the hot water reservoir hmm Warmwasserspeicher, let's wait one minute, two minutes, 5 minutes. Nothing, ok I need a screwdriver. Found the screwdriver. Test one, test two, nothing. Ok, tomorrow I try again. Whatsapp, hi mom, all good, no don't worry, I'm fine. Heeey hi, yes it's been a while, hahaha, If I like Pedro Pascal? Of course I like him, who doesn't? What? Communist? Well, you had a dictatorship in Chile I kind of understand how it hits. Hm. Right, well, I tend to the left spectrum so it's hard to say something. Oh it's fine, you can write in Spanish if you prefer, I'll understand. Hm. Well, I'd still understand him being progressive? Oh the Apple ads, he did, well, yes, entiendo todo lo que dijiste, es contradictorio. Quizás él estaría dispuesto a apoyar temas progressistas, o ligeras intervenciones del Estado en servicios básicos. Hahaha, gotcha, yes, ok, well, I guess I need a shower, have a good evening! the 5th on Sunday then. Okay, cool. Oh wow, it's 21:00, I should be sleeping, I'll try to sleep. Where's my book? Livi, come here, lay down on your bed, Schatzi. Yes, super. I love you, you're the cutest. Tomorrow we take a longer walk ok? Sleep tight, love. I promise you from tomorrow on life will be today.

CONTENT Warning: This post talks about suicide while actually using the word suicide. (More specifically, it discusses heavy feelings of suicidal ideation, my own suicide attempts, research on deaths by suicide with efforts to reduce stigma, and strong opinions you may not agree with).

Last year today, after languishingly slip p ing through another day at a job I loved, I coached my dispirited body towards the bus stop, an apparition. For months I had been contending with gravity, like dial-up during my mom’s endless phone call, I was sprinting, and somehow stagnant. A variant of one vow propelled me through each day: You can kill yourself tonight. You can kill yourself tomorrow. You can kill yourself this weekend. Fueled by the promise of relief, I got off the bus near the Secretary of State, a not-so-subtle SOS. It was my 35th birthday. My challenge: To buy 35 items from the dollar store I could end my life with.

Creativity and determination have always been my strong suits. When pushed to full VOLUME, they drown out all attempts at logic, any willingness to see another perspective. “This is my decision, my choice. It has nothing to do with them. People who don't support it, just don't understand. I've exhausted all options, I've exhausted exhaustion. There is no alternative.” Today I know, I was unable to see A L L the other options. I couldn’t see how distorted my thinking was. I couldn’t access a faith that I would ever feel differently. I couldn’t remember a time I wasn't consumed with immobilizing heaviness. I was wrong.

The thing about suicidal ideation, in silence it swells, leaving little room for any other thoughts. It feeds off whispers around corn ers, off unspoken I love yous. It fills the spaces where words do not form: theydon’tunderstandyou;there’ssomethingwrongwithyou,youwillneverbelonghere,youarenotlikeeveryoneelse;earthwasnevermeantforyou. The only fertilizer worse than silence: words that validate, voices of others who do not challenge, but affirm. Last year, for over six months, I could only see one option. For someone who is non-binary, it is baffling how often I only see two paths in front of me, live or die. Fortunately, the nature of existence is things will change.

Last week someone I knew died by suicide. This person has lived on my top ten list of leaders I aspire to be for years, and will likely remain in that spot. I wasn’t close with this person. I wont pretend to know the complexity of their circumstances or their choice to choose suicide. I would be lying to say I’m not alarmed and concerned at the public narrative around their suicide in the last week, and the tone of celebration, specifically from community leaders. All I know is a faint sliver of light, in the vast shadows of all I don’t. I have been wrong often. I don’t know if the outcome could have been changed. I don’t know that this person’s experience is even remotely related to mine. Something I do know, Something I believe deeply: No human should have the power to play God. No amount of public influence or closeness of relationship should make someone eligible to decide whether another’s life is worth ending. No human can honestly discern whether someone is having a serious mental health crisis or a spiritual awakening.

I have attempted suicide 9 times. I have stayed in more psych hospitals than I would like to admit. During these stays, I can confidently estimate that around 60% of the people I met on those hospital floors would tell me they were having a spiritual rebirth, that their eyes were open to what others just couldn’t see. Maybe they really were. As a human with a history of addiction and trauma, I’ve witnessed misinformation, ignorance, victim blaming, sexism, and transphobia from doctors, nurses, and even social workers. Still, at the end of the day, I would defer to a team of health professionals in deciding the health and wellbeing of someone else. Even if I’m a mental health professional, even if I had a deep knowing a person I loved was having a spiritual reckoning. As a Trans human, I dance daily between wishing I didn’t have to be here or fearing that I will die at the hands of someone else. This fear of being murdered is something Black folx have had to live with for generations. I may know the struggle of being too soft, too sensitive for this world, of having addiction and mental illness. I know nothing of the pain and unkindness that comes with living in a Black body. No human should have to carry that weight.

The fact is, when someone dies by suicide, there will always be unanswered questions. It will never make sense, even to those with a shared experience of SI.

My number of suicide attempts is even with my ACE score. The CDC says that individuals with an ACE score of 4 or higher are 12 times more likely to die by suicide (CDC, 2026). Perhaps, my attempt was inevitable. Over 40% of Trans adults in the US have attempted suicide. Maybe it my turn? Maybe it was genetics? Maybe it was mental illness? Maybe I just clearly saw the darkness of the world in a way that other people couldn't? Maybe it’s a combination of a hundred other reasons?

At the end of the day I cannot dwell on the why because the reason doesn’t matter. I can only share the facts: </3 The World Health Organization names suicide as the 10th leading cause of death in the country, with it officially displacing COVID 19 in 2024. WHO also names stigma as the largest barrier.

</3 Silence feeds stigma. Avoiding the conversation feeds stigma. Refusing to clearly state that someone died by suicide and use that opportunity to dispel myths or share risks, research and resources further feeds stigma. This is the Papagano Effect.

We know that people who know someone who died by suicide are three times more likely to die by suicide (NLM, 2022).

We know that talking about it decreases the likelihood that others will die by suicide, and still we choose not to talk about it or use the opportunity to shatter the stigma.

I am many things, none of which define me. I have debilitating depression that, at times, makes it impossible to see anything objectively, a fog so lightless it makes it impossible to see any exit sign that doesn’t read: DEATH.

When I repeatedly told my friends my own version of “I cracked the code”, that I had no other options but to end my life. They didn’t respect my wishes. They didn’t choose to empower me or my autonomy. They called social workers. If they had not I wouldn’t be here.

Today I ask myself, was it ever really my choice? More often than not people who die by suicide are under the impression of mental and emotional anguish? Can they objectively make that decision? Or did they have died from the last symptom of a terminal biological health condition that causes major deficits in decision-making and information processing?

I am by no means claiming that everyone who dies by suicide has mental illness. Diagnoses aside, We know that mental suffering is part of the human condition. We know as humans our brains evolve to help us survive, and if someone's brain is convincing them to die, likely something is wrong.

There is an tone of glamorization when we describe suicide through common platitudes or try to justify it “they wanted to be free” “they were tired” “we can offer our unconditional love and acceptance.”

Without labeling their mental state, why not be truthful about their cause of death? Someone dies by suicide every 11 minutes (John Moe, 2026). If sharing this reality can help even one person, why not have an honest conversation?Why not dissolve the power that silence gives the word?

They died by suicide.

Here are a few common narratives about suicide that are false and need to be publicly disproved (Mayo Clinic, 2024).

MYTH: Once someone decides to end their life, nothing can stop them. FACT: Effective intervention and reducing access to lethal means can save lives.Most people struggling with suicide are ambivalent. Those who survive a suicide attempt often express relief. 90% of suicide attempts do not going on to die by suicide (Harvard.edu).

MYTH: Asking someone about suicide will “plant the seed” or encourage them to act. Talking about suicide increases the chance a person will act on it. FACT: Talking about suicide may reduce, rather than increase, suicidal ideation. It improves mental health-related outcomes and the likelihood that the person will seek treatment. Opening this conversation helps people find an alternative view of their existing circumstances. If someone is in crisis or depressed, asking if they are thinking about suicide can help, so don't hesitate to start the conversation.

MYTH: Suicide is a choice. People who die by suicide are selfish, cowardly or weak. Fact: People don't die of suicide by choice. Often, people who die of suicide experience significant emotional pain and find it difficult to consider different views or see a way out of their situation. Even though the reasons behind suicide are complex, suicide is commonly associated with illnesses, including depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, substance use, chronic pain or respiratory issues, neurological disorders, and cancer.

References:

https://hsph.harvard.edu/research/means-matter/means-matter-basics/attempters-longterm-survival/

Surfing And Humility

Surfing saved my life.

That’s an over-dramatic way of putting it. Perhaps the more accurate thing to say is that surfing has played an integral role in the working out of my salvation, a grace from God that helps me better understand His grace overall. But saying “surfing saved my life” grabs one’s attention a little bit better.

I’d grown up a skateboarder, starting in the summer of 1996, which put me adjacent to surfing. Over the next four years or so, I’d be in surfing’s orbit in some form or another—either by being in stores that sold clothing and accessories related to both or because my youth pastor, who taught me a lot about skateboarding, was also a surfer and was trying to get me and my best friend to join him some Saturday.

My mom was not a beach person. So I seldom saw the ocean growing up. We lived in Orlando, which meant a trip to the beach would have been an event (at least an hour’s worth of driving each way). But I was very much into things like snorkeling and SCUBA. My first ever job was at a pet store that specialized in fish and I became borderline obsessed with the little critters to the point that I briefly considered ichthyology as a career. Which is all to say that I had a sort of hunger for the sea.

***

I’ve written about it before, but I was a kind of misfit kid. I didn’t really fit in with a lot of people, except my best friend and his little brother (who were practically family to me). I was too “Christian” for a lot of the cool kids at my school (even though it was a Baptist school), but also too alternative and grungy for the youth group set at the time. I fought with school administrators almost every day and openly rebelled against much of the fundamentalist elements in our church. I got really good at “code-switching” when around certain groups, only really feeling like myself when I was with friends or alone at home.

During my junior year of high school (second-to-last year before graduation, for those readers who might have a different school system) I got kinda tired of fighting with everyone. I watched Office Space for the first time and it opened my mind to a completely different way of thinking: not giving a shit. I decided to just do what I wanted to do. And I decided, after winter break, that I wanted to play baseball.

I worked hard. I carried a baseball with me everywhere like I was Pistol Pete and his basketball. I was throwing and catching after school, going to batting cages. I was hitting solid line drives off the 90 MPH pitching machine. But, I did not make the cut. I have my suspicions about this (my mom worked for the church of which my school was parochial and there had been long-simmering tensions between the two institutions; none of the church staff kids were picked that year). Regardless, this turned out to be a God-send because one day I was skating at the church and my best friend shows up and tells me that he and Eddy (our youth pastor) had gone surfing together and that it was awesome. He told me “my dad is going to take us to the beach tomorrow, you should come.”

That day would have been the date of my first baseball game had I made the team.

We drove to New Smyrna Beach, rented long boards, and waded out into the freezing cold water. I was in a wetsuit (I was taking SCUBA lessons as part of a Marine Biology class, so had acquired one as part of this, thankfully). I don’t remember much about the conditions. All I remember was taking the board to the white water and trying to catch whatever was breaking. New Smyrna, at high tide, has a long flat section of shallow water (which makes it ideal for kids playing at the beach and why it’s a popular family spot) and so I was pushing off the sand and into white water.

I’ll never forget standing up for the first time. The wave was maybe shin-high, and I was basically going straight toward the beach. But the speed and the simple fact that I was being moved by a small amount of water shifted something deep in my mind. I wound up getting hit by my board later that day, which also left an impression (both literally and figuratively):

there was something much bigger than me out there.

***

I was an angry kid. Apparently this is not uncommon for young men who grow up without fathers. My dad left my mom as soon as he found out she was pregnant with me and I never met the man (he died in July of last year). I don’t consider myself someone with “daddy issues” or whatever. But I do agree with something Donald Miller writes about in his book for guys who grow up without dads, entitled To Own A Dragon, where he notes that fathers (or father-figures) are key in helping young men learn to channel their aggressions and frustrations. We have a lot of testosterone, which is necessary for our development, and it begins to mess with us in our teenage to young adult years. Someone who’s been through it can help us navigate the path. I did not have that person.

I had a bunch of anger pent up and I took it out on authority figures, or on people that I felt were hypocritical. It often felt like the world was out to get me somehow. Plus, I was smart in a way that didn’t quite fit with my Baptist school environment (I excelled in creative pursuits; I was also quite good in history and Bible, which did afford me some accolades, but I hated doing homework and so my grades did not reflect, to the school’s eyes, my abilities). I was a self-centered little snot who thought he was smarter and better than everyone else around him. I did not realize it at the time, but I needed to get my ass kicked around a bit, on a kind of spiritual level.

***

One of my favorite surfing stories, one that has woven itself into the fabric of our shared mythology, is the story of Greg Noll’s last wave. The short version of the story is this: during an immense swell that hit the Hawaiian islands during the winter of 1969, Noll paddled out at Makaha (in defiance of law enforcement) and caught what people have said was the largest wave surfed at the time. Noll, known for his bombastic nature, allowed the size of the wave to get bigger in the retelling: first 50 feet, then 70, and so on. Regardless of the size, what’s true is that Greg Noll caught this wave, came in, loaded his board onto the roof of his car, and never surfed again. He continued to shape surfboards and be part of the industry. But he never paddled out again.

There are numerous interviews about this. The reason Noll gives for quitting surfing was that he had reached a point in life where, in his own words, he was begging God to send him a wave that he could not ride. He challenged God and God answered. He said that that wave humbled him and made him realize that he could not continue down this path anymore. Surfing was going to kill him because he did not know how or when to stop. Until that wave made that decision for him.

I love this story because it feels true to my situation. For Greg Noll, it took an eternally-growing wave to put him in his place. For me, it took an ankle-high roller.

I learned from that tiny wave that I was not the center of the universe. I would come to learn that I am a recipient of God’s grace, surfing the waves He sends.

***

That day of surfing set me on my path. I caught a wave that I’m still riding. If not for surfing, I would not be who and where I am today. Surfing would teach me about humility and God’s grace. It would also become a deciding factor in where I went to college, which would put me right in front of the Episcopal parish that would reignite my Christian faith after a few years of faltering. This would, of course, lead to my call to the ordained priesthood. It would also predispose me toward Hawai’i, the birthplace of surfing.

It was in March of 2000 that I first surfed. And it was in March of 2020 that I would begin my life in Hawai’i. There is a fairly straight line between those two points.

Had I remained an angry young man, I might’ve gone down a similar path as my dad. But God had other plans in mind.

So, yeah, surfing saved my life.

***

The Rev. Charles Browning II is the rector of Saint Mary’s Episcopal Church in Honolulu, Hawai’i. He is a husband, father, surfer, and frequent over-thinker. Follow him on Mastodon and Pixelfed.

NOTE: The header photo is the only known close-up photo I have of myself surfing. It was taken by my friend Kurt probably in the summer of 2004 when I lived in Fort Pierce Florida. I’m surfing a kinda busted Yater Spoon that I bought on the cheap from Spunky’s Surfshop, a board that would also play an important role in my spiritual life, which I’ll write about some other time.

#Surfing #Spirituality #Christianity #Jesus #Theology

The Long Road of Sons and Daughters: Learning to Run the Race Set Before Us

from Douglas Vandergraph

There is a moment that comes to nearly every human life when the soul begins to realize that faith is not merely something we talk about, but something we must live through with endurance. Hebrews 12 opens with imagery that feels almost cinematic when you slow down enough to truly see it. The writer invites us to imagine ourselves running a race, but not a quiet solitary jog through empty countryside. Instead we are running inside a vast stadium surrounded by what Scripture calls a great cloud of witnesses. These witnesses are the faithful who came before us, the men and women whose lives were marked by courage, perseverance, and trust in God even when their circumstances seemed impossible. Their presence is not meant to intimidate us, but to remind us that we are part of something larger than our own short lifetime. Faith is not a private hobby practiced in isolation; it is a living story stretching across centuries, carried forward by one generation after another. Every believer who has ever trusted God through hardship becomes part of that cloud. And when we begin to understand this picture deeply, we start to realize that our own lives are not random or unnoticed but connected to a sacred unfolding story that continues to move forward through us.

The race described in Hebrews 12 is not about speed, and it is certainly not about comparison. One of the subtle mistakes many people make in their spiritual lives is assuming that faith should look impressive to others. We sometimes imagine that the strongest believers are the ones who appear to move effortlessly through life, never stumbling and never struggling. But the language of endurance tells a different story entirely. Endurance assumes difficulty, resistance, and moments where continuing forward requires deep inner resolve. The race of faith is not won by those who sprint early and collapse later, but by those who continue placing one step in front of the other when their legs feel heavy and their breath feels short. In other words, Hebrews 12 speaks to the long obedience of the soul. It acknowledges that the journey with God often unfolds across years of quiet perseverance rather than dramatic moments of triumph. When people hear the phrase “run with endurance the race set before us,” they sometimes overlook the deeply personal part of that sentence. The race set before us is not identical for every person. Each life carries its own terrain, its own hills, its own unexpected storms, and its own moments where the path feels lonely. Yet God remains present in every one of those landscapes, guiding the runner who continues forward in trust.

The writer of Hebrews also introduces one of the most liberating ideas in the entire passage when he tells us to lay aside every weight and the sin that clings so closely. The difference between those two categories is worth careful reflection. Sin is the obvious burden that pulls us away from God’s design for our lives. But weights can be more subtle. A weight might not be inherently sinful, yet it still slows our progress. Sometimes weights appear in the form of distractions that consume our time and attention. Other times they appear as fears we have carried for so long that they begin to feel normal. Many people unknowingly run their race while dragging emotional baggage that God never intended them to carry. The invitation of Hebrews 12 is not simply to try harder, but to travel lighter. When we release the unnecessary burdens that entangle our hearts, the journey with God begins to feel different. Faith becomes less about grinding effort and more about clear direction. It becomes possible to see the path ahead because our vision is no longer clouded by everything we have been dragging behind us. This idea alone has the power to transform how we think about spiritual growth. The goal is not to prove our strength by carrying every burden imaginable, but to trust God enough to release what no longer belongs in our hands.

At the center of the entire passage stands a single phrase that anchors everything else: looking to Jesus, the author and finisher of our faith. This statement contains a depth that cannot be exhausted by a quick reading. To call Jesus the author of faith means that faith itself begins with Him. Our relationship with God is not something we invent through our own spiritual creativity. It begins because God first reached toward us. Long before we ever took our first uncertain steps toward faith, Christ had already stepped into human history to make reconciliation possible. But the passage goes even further by calling Him the finisher of our faith. This means that the story does not end with our fragile beginnings. Jesus does not merely start the work and then leave us alone to complete it. He remains present throughout the entire process, guiding, shaping, correcting, and strengthening the believer as life unfolds. When people feel overwhelmed by the weight of their own imperfections, this truth becomes profoundly comforting. Faith is not sustained by our perfection but by Christ’s faithfulness. Our role is not to manufacture spiritual power but to keep our eyes oriented toward the One who carries the story forward.

The writer then reminds us that Jesus endured the cross for the joy set before Him. This phrase has puzzled many readers over the centuries because the cross represents unimaginable suffering. Yet Hebrews insists that joy existed on the horizon beyond that suffering. The joy was not the pain itself but the redemption that would flow from it. Jesus saw what would be accomplished through His sacrifice. He saw the restoration of humanity’s relationship with God. He saw the possibility of millions of lives being transformed through grace. He saw people who had been trapped in despair discovering hope again. When Christ looked toward the cross, He was looking through the pain toward the restoration it would bring. This perspective carries enormous implications for our own struggles. When believers face seasons of hardship, we often interpret those moments as meaningless suffering. But Hebrews invites us to consider that God may be working toward outcomes we cannot yet see clearly. Faith allows the soul to hold onto hope even when the present moment feels heavy. It does not deny the difficulty of the road, but it refuses to believe that the road ends in darkness.

Another powerful dimension of Hebrews 12 emerges when the writer begins to speak about discipline. In modern culture the word discipline often carries negative associations. Many people hear the term and immediately imagine punishment or rejection. But the passage frames discipline in an entirely different light by connecting it to the identity of being God’s children. Discipline, according to Hebrews, is evidence of belonging. Just as a loving parent guides and corrects a child in order to help them grow into maturity, God shapes the lives of those He loves. This process is rarely comfortable in the moment. Growth seldom is. Yet the writer insists that discipline ultimately produces a harvest of righteousness and peace for those who have been trained by it. The language here is agricultural and patient. Harvests do not appear overnight. Seeds are planted, seasons pass, storms come and go, and only after time does the fruit begin to appear. Spiritual maturity follows a similar rhythm. God’s work in our lives unfolds gradually through experiences that stretch our character and deepen our trust. The discipline we experience today often becomes the strength we depend upon tomorrow.

This understanding of discipline helps believers reinterpret many of life’s difficulties. Instead of seeing hardship as evidence that God has abandoned us, Hebrews suggests that some challenges may actually be part of God’s refining work. This does not mean that every painful experience is directly orchestrated by God, but it does mean that God is capable of bringing growth out of circumstances that initially appear discouraging. The soul that learns to trust God through these seasons becomes resilient in a way that cannot be manufactured through comfort alone. Over time the believer begins to recognize that faith is not fragile after all. It can withstand storms because it is rooted in something deeper than temporary circumstances. The Christian life therefore becomes less about avoiding difficulty and more about discovering God’s presence within it. When we begin to view our struggles through this lens, even the hardest seasons can take on new meaning. The road may still be difficult, but it is no longer empty of purpose.

Hebrews 12 continues by encouraging believers to strengthen their weak hands and steady their trembling knees. The imagery here suggests a community that supports one another through the race of faith. Christianity was never intended to be lived entirely alone. The early believers understood that encouragement, accountability, and shared wisdom were essential for spiritual growth. When one person grows weary, another can remind them why the journey matters. When someone begins to lose heart, another voice can gently guide them back toward hope. This communal dimension of faith reflects the heart of the gospel itself. God did not design humanity for isolation. We flourish when we walk together toward the same source of life. The call to strengthen one another therefore becomes part of the race itself. Every act of encouragement becomes a way of helping someone else continue forward.

The writer then urges believers to pursue peace with everyone and to pursue holiness without which no one will see the Lord. These two pursuits belong together more closely than many people realize. Peace reflects how we relate to others, while holiness reflects how we orient our hearts toward God. Both are necessary because faith expresses itself in both directions. A person cannot claim deep spiritual devotion while consistently creating division and hostility around them. At the same time, peace that ignores the call to holiness becomes shallow and temporary. Hebrews invites believers into a life where inner transformation and outward relationships move in harmony. The more a person grows in closeness with God, the more their character begins to reflect the patience, compassion, and integrity that Jesus displayed. Holiness therefore becomes less about rigid rule-keeping and more about allowing God’s presence to reshape the entire landscape of the soul.

The passage also contains a sober warning about bitterness. The writer describes bitterness as a root that can grow quietly beneath the surface and eventually cause trouble for many people. This imagery is remarkably accurate to real human experience. Bitterness rarely appears suddenly in full form. Instead it begins as a small wound that remains unresolved. If that wound is continually revisited without healing, it begins to deepen. Over time the bitterness spreads outward, influencing how a person interprets other relationships and circumstances. What started as a single hurt eventually colors the entire emotional landscape of a life. Hebrews calls believers to remain vigilant against this process because bitterness can slowly erode joy, gratitude, and trust. The antidote is not pretending that pain never occurred, but bringing those wounds honestly before God so that healing can begin. Forgiveness does not erase the past, but it prevents the past from imprisoning the future.

One of the quiet turning points in Hebrews 12 arrives when the writer contrasts two mountains that represent two entirely different spiritual realities. The first mountain is Sinai, the place where the law was given amid thunder, fire, darkness, and trembling. The imagery is intense and overwhelming because Sinai represented a moment when humanity encountered the holiness of God in a way that revealed how distant and unapproachable that holiness seemed. The people who stood at the base of that mountain were terrified, not because God desired to frighten them, but because the raw power of divine holiness exposed the limitations of human righteousness. Even Moses, who stood closer to God than almost anyone in that moment, described himself as trembling with fear. Sinai revealed something profoundly true about the human condition: left to our own efforts, we cannot climb high enough to reach God. The law was never meant to serve as a ladder by which humanity could earn its way into heaven. Instead it revealed the depth of our need for grace.

But Hebrews does something remarkable after describing Sinai. It tells believers that they have not come to that mountain. Instead they have come to Mount Zion, the city of the living God, the heavenly Jerusalem. The atmosphere shifts completely when the writer begins describing this second mountain. Instead of thunder and terror, there is celebration. Instead of distance, there is welcome. Instead of trembling fear, there is joyful assembly. Zion represents the fulfillment of what Sinai pointed toward. Through Christ, believers are invited into a relationship with God that is no longer defined by separation but by reconciliation. The writer describes an innumerable gathering of angels, the assembly of the firstborn who are enrolled in heaven, and God Himself standing at the center of it all. It is an image of belonging that stretches beyond anything the human imagination normally conceives. Faith, according to Hebrews, is not merely about moral improvement or spiritual discipline. It is about being welcomed into a living community that spans heaven and earth.

At the center of this gathering stands Jesus, described as the mediator of a new covenant. The word mediator carries immense weight because it captures the bridge that Christ forms between God and humanity. Under the old covenant, the people relied on priests and sacrifices that had to be repeated continually. Each sacrifice pointed toward the seriousness of sin but could never permanently remove its power. The blood of animals symbolized atonement, yet it remained only a shadow of something greater that was still to come. When Hebrews speaks of the sprinkled blood of Jesus that speaks a better word than the blood of Abel, it is drawing on a story from the earliest pages of Scripture. Abel’s blood cried out from the ground as a testimony to injustice and violence. The blood of Christ, however, speaks a different message entirely. It speaks forgiveness rather than accusation. It speaks reconciliation rather than judgment. It speaks restoration rather than exile. Through Christ, the relationship between God and humanity is not merely patched together but transformed into something entirely new.

The writer then delivers a warning that carries both urgency and compassion. He urges readers not to refuse the One who is speaking. Throughout the history of faith, God has spoken in many ways. Sometimes His voice came through prophets, sometimes through Scripture, sometimes through quiet conviction within the human heart. But Hebrews insists that the clearest and most decisive expression of God’s voice came through Jesus Christ. To ignore that voice is not simply to miss a helpful piece of advice; it is to turn away from the very source of life. Yet the warning is not meant to produce fear alone. It is meant to awaken awareness. God continues to speak because He desires relationship. The call to listen is therefore an invitation to remain open to the transformation that God is continually offering.

The passage concludes with a powerful image of God shaking the heavens and the earth. This idea may initially sound unsettling, but its deeper meaning becomes clearer as the writer explains it. The shaking represents the removal of what cannot last so that what is truly permanent can remain. Much of what humans build throughout life feels solid and secure in the moment, yet history repeatedly reminds us how fragile those structures can be. Wealth, status, cultural trends, and political systems all rise and fall across generations. Hebrews invites believers to anchor their lives in something that cannot be shaken. The kingdom of God stands beyond the instability of human systems because it is rooted in God’s eternal character. When believers place their hope in that kingdom, they begin to experience a stability that circumstances alone cannot provide.

Receiving this unshakable kingdom leads naturally to gratitude. The writer calls believers to respond with reverence and awe, recognizing the holiness of the God who welcomes them into His presence. Reverence does not mean shrinking away in fear. Instead it reflects a deep awareness of the sacredness of the relationship we have been invited into. When someone truly understands the grace they have received, gratitude becomes the natural posture of the heart. Worship stops being a weekly ritual performed out of obligation and becomes a sincere response to the beauty of God’s character. The more deeply we recognize what Christ has done, the more naturally reverence flows from within us.

One of the quiet miracles of Hebrews 12 is how it reshapes the way believers think about their own lives. Instead of viewing life as a random series of disconnected events, the passage reveals a larger narrative unfolding beneath the surface. Every challenge becomes part of a race being run. Every moment of discipline becomes part of a training process shaping the soul. Every act of encouragement becomes part of a community journeying together toward the same destination. And every step of faith becomes part of a story that stretches from the earliest witnesses of Scripture all the way into eternity. When people begin to see their lives through this lens, the ordinary moments of daily existence take on deeper meaning. The quiet decisions we make, the kindness we offer, the patience we practice, and the trust we extend toward God all become threads woven into a much larger tapestry.

There is also something profoundly comforting about the realization that the race of faith does not depend on flawless performance. Hebrews never asks believers to run perfectly. Instead it asks them to run faithfully. The difference between those two ideas is enormous. Perfection focuses on avoiding every possible mistake. Faithfulness focuses on continuing forward even after mistakes occur. The writer of Hebrews understood that human beings stumble. That is precisely why he continually directs attention back toward Jesus. When our eyes remain fixed on Christ, failure no longer becomes the final word. Grace remains larger than our missteps, and the path forward remains open.

As believers move through life, they eventually begin to notice that the race described in Hebrews 12 contains seasons of both intensity and quiet endurance. Some moments feel dramatic and decisive, like crossing a mountain pass where the view suddenly expands. Other moments feel ordinary, like walking mile after mile through terrain that looks almost unchanged. Yet both types of seasons play essential roles in the formation of faith. The dramatic moments remind us of God’s power and presence in unmistakable ways. The quiet stretches teach us perseverance and trust. Over time the believer begins to recognize that God is present in both kinds of seasons. The mountaintop and the valley both become places where the soul learns to depend on Him.

The imagery of the great cloud of witnesses also begins to feel more personal as life unfolds. When we read about the faithful figures described earlier in Hebrews, they may initially seem distant and almost mythical. But as the years pass, we begin to encounter people in our own lives who embody similar courage and devotion. Perhaps it is a mentor who quietly lived with integrity for decades. Perhaps it is a parent who endured hardship without losing faith. Perhaps it is a friend who continued to trust God through circumstances that would have broken someone else. These individuals become part of our own cloud of witnesses, reminding us that the race can indeed be finished well. Their stories encourage us to keep running when our own strength feels thin.

The invitation of Hebrews 12 ultimately leads believers toward a life of profound hope. The passage acknowledges suffering, struggle, and discipline without minimizing their difficulty. Yet it refuses to allow those realities to define the entire story. The race has a destination. The training has a purpose. The shaking has an outcome. The kingdom that awaits believers cannot be shaken because it is built upon the unchanging character of God Himself. When the soul truly absorbs this truth, anxiety about temporary circumstances begins to lose its grip. The future no longer appears as an unpredictable threat but as a continuation of the story God is already guiding.

And so the believer continues forward, sometimes running with strength, sometimes walking slowly, sometimes leaning on others for encouragement, but always moving toward the One who began the journey in the first place. The path may twist and rise in ways we did not expect, but the destination remains secure. Jesus, the author and finisher of our faith, remains ahead of us, beside us, and within us all at once. The race is not solitary, the road is not meaningless, and the finish line is not uncertain. It is held firmly within the promise of the God who calls His sons and daughters home.

Your friend, Douglas Vandergraph

Watch Douglas Vandergraph’s inspiring faith-based videos on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/@douglasvandergraph

Support the ministry by buying Douglas a coffee: https://www.buymeacoffee.com/douglasvandergraph

Financial support to help keep this Ministry active daily can be mailed to:

Vandergraph Po Box 271154 Fort Collins, Colorado 80527

The First Family and the Courage to Face Honest Questions

from Douglas Vandergraph

There are moments in every sincere spiritual journey when a person encounters a question in Scripture that feels too direct to ignore. These questions are not signs of weak faith. They are often the doorway into a deeper, more mature relationship with truth. One of those questions has circulated for generations, quietly passing between curious minds who are reading the earliest pages of the Bible and trying to understand the world they describe. The question is simple enough that a child might ask it, yet profound enough that many adults hesitate before answering it out loud. If God created Adam and Eve, and Adam and Eve had sons named Cain and Abel, then where did their wives come from? The question is not hostile toward faith. It is the natural result of reading the story carefully and wanting the details to make sense. When people finally give themselves permission to ask it openly, something important happens. Instead of weakening faith, the honest pursuit of the answer often strengthens it because it reveals the depth and realism of the biblical narrative.

The opening chapters of Genesis introduce us to the beginning of the human story. They describe a moment when humanity did not yet exist and then suddenly did. According to the biblical account, God formed Adam from the dust of the ground and breathed life into him. Shortly afterward, Eve was created as Adam’s companion, completing the first human relationship. From that point forward the story begins to move, not through abstract ideas, but through family. The Bible does not present the beginning of humanity as a mass creation of millions of people scattered across the earth. Instead, the entire human race begins with one couple. This design immediately tells us something about the way God intended human life to unfold. Humanity was meant to grow, multiply, and expand through generations of family relationships. The first two humans were not simply individuals placed on the earth. They were the starting point of a lineage that would eventually become every nation, culture, and language that exists today.

When we reach the story of Cain and Abel, the narrative focuses on two sons whose lives take very different directions. Abel becomes known for offering a sacrifice that pleases God, while Cain becomes remembered for committing the first act of murder in human history. The tragedy of that moment echoes throughout the entire biblical storyline because it shows how quickly human freedom can drift away from God’s design. After Cain kills Abel, the story continues, and that is where the question naturally arises. Cain eventually leaves and builds a life for himself, and Scripture tells us that he had a wife. For readers who are thinking carefully, the question becomes unavoidable. If Adam and Eve only had two sons, where did this wife come from?