Want to join in? Respond to our weekly writing prompts, open to everyone.

Lent 2026 Day 11 - War

from Dallineation

I woke up to the news that the USA and Israel launched a major military strike against Iran. It is natural to feel worry and fear over what this might mean not only for innocent people in Iran, but of the surrounding region and even the world. And then I read the Daily Readings from the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops.

Today's Gospel reading is from Matthew 5:43-48.

Jesus said to his disciples: “You have heard that it was said, You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy. But I say to you, love your enemies, and pray for those who persecute you, that you may be children of your heavenly Father, for he makes his sun rise on the bad and the good, and causes rain to fall on the just and the unjust. For if you love those who love you, what recompense will you have? Do not the tax collectors do the same? And if you greet your brothers and sisters only, what is unusual about that? Do not the pagans do the same? So be perfect, just as your heavenly Father is perfect.”

It is heartbreaking that this is still a radical idea almost two thousand years after it was taught by Our Lord.

War is incompatible with the teachings and example of Jesus Christ.

I am a proponent of nonviolence and have been following several organizations dedicated to activism, teaching, and promotion of peace and nonviolence.

One of the organizations I have learned about is a Catholic organization called Pax Christi International. From their website:

Pax Christi International is the global Catholic peace movement dedicated to promoting Gospel nonviolence, justice, and reconciliation rooted in Catholic social teaching. For decades, Pax Christi International has been calling for a deep reflection on the failure of war and violence and for investment in effective nonviolent tools for reconciliation to nurture the just peace essential to alleviating intense human suffering.

Today, Pax Christi issued a statement condemning military strikes against Iran and calling for deescalation, dialogue, and respect for human dignity.

Pax Christi also referred to their Pax Christi International Declaration on Iran, published on February 11th. I encourage you to read it.

I am grateful that there are Christians of good conscience everywhere who are willing to stand up and state clearly the doctrine of Christ, calling for love, understanding, and peace in the face of war.

#100DaysToOffload (No. 141) #faith #Lent #Christianity #politics

from Grasshopper

Κατακτηση

Η στιγμή στην οποία αυτός ο σκλάβος απο το Πουέρτο Ρίκο (Bad Bunny) περιγράφει την πραγματικότητα πιο επιδραστικά κ αξιακα φορτισμένα όσο λίγοι στο πιο δημοφιλές σανίδι του πλανήτη (half time superbowl 2026) είναι μια στιγμή αληθινής γιορτής!

Σηματοδοτεί το όλοι ξέρουν οτι όλοι ξερουν.

Πιο απλά απο όλους το περιέγραψε ο τραμπ μόλις αντιστραφει η ανάρτηση του.

Πολλά αρχίδια και αδάμαστη θηλυκότητα.

The Fire a Father Leaves Behind

from Douglas Vandergraph

There comes a moment in every parent’s life when the noise of the world fades for a second, the pace slows just enough to breathe, and a single question rises to the surface with a quiet intensity that cannot be ignored. What will my children remember about me when I am gone? Not the things I bought them, not the schedules we kept, not the vacations or the milestones or the chaos that seemed so urgent at the time, but the real legacy—the deep, enduring imprint that outlives the body and reverberates in the generations that follow. For me, that question has narrowed itself into one truth that burns like a living ember in my chest: above everything else, I want my children to know that their father was never ashamed of his faith in Jesus. I want them to look back one day, whether in moments of heartbreak or triumph or confusion or joy, and be able to say with absolute clarity that their father stood unapologetically, unwaveringly, and joyfully anchored in the One who held him together. Because the older I get, the more I see how fragile life is, how easily noise becomes distraction, and how quickly distraction becomes identity. And in the midst of that chaos, faith is not something you wear—it is something you live, something you breathe, something your children cannot help but notice even when you never say a single word.

We live in a world that has mastered the art of silencing believers. A world that tells you to tuck your faith away for the sake of politeness, to dilute your convictions so no one feels uncomfortable, to speak softly about Jesus as though His name is fragile. But I refuse to raise my children in a home where fear determines boldness. I refuse to let the world teach them that silence is safer than truth or that hiding what you believe is more honorable than living it out loud. Real strength has never been about appearance; it has always been about the quiet posture of a heart that still bows when it hurts, still trusts when it trembles, and still prays when everything seems to fall apart. My children need to see that—not the version of strength the culture markets, not the hollow confidence that grows from ego, but the rugged, weather-beaten courage that is born from prayer, repentance, and surrender. I want them to see that real men cry out to Jesus when they cannot fix it, real women lift their eyes when they cannot lift their burdens, and real faith is not a trophy—it is a lifeline. And when they grow up in a home where prayer is normal, forgiveness is practiced, and love is fierce and humble and costly, faith stops being a concept and becomes a living, breathing presence.

There is something indescribable about the way a child watches their parent pray. It marks them without a single sentence. It teaches them what reverence looks like. It teaches them where strength comes from. And it teaches them that the authority of a parent is not self-generated—it is borrowed from God. I want my children to walk into adulthood knowing that their father’s strength never came from discipline alone, ambition alone, or confidence alone. It came from the hours spent in the unseen places, where I brought my fears, my failures, my questions, and my weariness before the God who never once turned me away. Children are far more perceptive than we give them credit for. They know when a parent is pretending. They know when a smile is forced, when confidence is performative, when a person is trying to project control that doesn’t exist. But they also know when faith is real. They know when peace that shouldn’t exist still settles in the room. They know when forgiveness that feels impossible still flows like a river. And they know when love is anchored in something bigger than human strength. That is the atmosphere I want my children to grow up in—not perfection, not plastic righteousness, but genuine dependence on Jesus that they can feel every time they enter the room.

When I think about legacy, I don’t think about monuments or accomplishments or recognition or anything the world counts as success. I think about eternal residue—the imprint a person leaves on the spiritual lives of their children long after their body returns to dust. I think about moments, not milestones. I think about the quiet nights when the world was asleep and I wrestled with God for the sake of my children’s future, for their protection, for their calling, for their hearts to be tender and their souls to be resilient. I think about the mornings when gratitude rose before stress had a chance to speak, and I thanked Jesus for the privilege of being their father even when I felt unqualified. I think about the moments when I failed, when I snapped, when I fell short, and how it was in those very moments that the power of forgiveness taught my children more than success ever could. Because when a parent is humble enough to repent, strong enough to change, and willing enough to love without condition, a child learns the gospel in a way that no sermon could ever match. I want them to see that faith is not a perfect performance; faith is a persistent return to the One who makes all things new.

Every generation has its own version of pressure, but this generation faces something far more insidious: the constant temptation to build identity on applause. Our children grow up in an environment where affirmation is addictive, comparison is relentless, and identity is outsourced to strangers on screens. They are told to curate themselves, to perform themselves, to brand themselves before they ever learn who they are. And in the middle of this digital storm, the greatest gift a parent can give their child is not a sense of accomplishment—but a sense of identity rooted in Christ. They need to know who they are before the world tells them who they should be. They need to see a parent who refuses to bow to the fear of other people’s opinions. They need to see someone who stands in the middle of cultural pressure with a calm, quiet confidence that comes from knowing that heaven’s approval outweighs earth’s applause. I want my children to see that my faith is not a hobby and not a performance; it is my foundation. When they watch me pray before decisions, praise God in storms, forgive when wronged, repent when needed, and remain faithful when life is shattering at the seams, they will understand that faith is not something you talk about—it is something you embody.

As the years pass, a parent begins to understand that the greatest sermons their children will ever hear are not the ones preached from pulpits, podcasts, or platforms, but the ones lived out in kitchens, cars, hallways, backyards, and quiet late-night conversations. The world tries to convince us that children need perfect parents, but what they actually need is present parents—humble parents—parents who are more committed to faithfully walking with Jesus than impressing anyone else. I want my children to know that their father’s faith was not a Sunday ritual or a cultural inheritance but a living fire inside his chest that reshaped his decisions, redirected his desires, and redefined what strength meant. I want them to know that every time I knelt down to pray, whether in desperation or gratitude or confusion or praise, I was leaving a trail they could follow when their own storms rise and their own hearts begin to tremble. They deserve to inherit a legacy that teaches them that courage is not pretending that life is easy but trusting Jesus when life is breaking. They deserve to see that forgiveness is not weakness but the kind of strength that only comes from surrender. And they deserve to watch their father love their mother, love them, and love others in ways that echo the heart of Jesus more loudly than any public declaration ever could.

There have been moments in my life that shaped me so profoundly I can still feel their weight, and I want my children to know those moments were not the result of my wisdom—they were the result of God’s grace. I want them to understand that every time I stood back up after failure, every time I refused to let shame define me, every time I chose to keep walking forward when discouragement tried to bury me, it was not because I am strong—it is because Jesus is faithful. And as they grow older and begin to face their own heartbreaks, disappointments, betrayals, questions, and crossroads, I want them to remember that their father never faced his battles alone. I want them to feel in their spirit that prayer is not a ritual reserved for crises but a constant lifeline that strengthens the soul long before trouble comes. I want them to see that obedience is not restriction—it is protection. And I want them to understand that the greatest victories they will ever experience will not be the ones earned by talent or strategy or opportunity, but the ones born out of faithfulness—those quiet, deeply personal moments when God steps in and rewrites the outcome.

There is something sacred about legacy because it weaves itself into the spiritual bloodstream of a family. Long after you are gone, long after your name is no longer spoken in daily conversation, the spiritual patterns you lived will continue shaping the generations that follow. A family that witnesses forgiveness becomes a family that practices it. A family that witnesses prayer becomes a family that depends on it. A family that witnesses sacrificial love becomes a family that reflects it. That is why I refuse to be ashamed of my faith in Jesus—it is not just about me. It is about the souls that will come from me. It is about the grandchildren I may never meet and the great-grandchildren whose names I will never know. It is about the spiritual ripple effect that begins with one person who decides that fear will not silence them, culture will not shape them, and apathy will not define them. It is about building a spiritual inheritance that outlives the noise of this world and anchors the hearts of future generations in something eternal, something unshakeable, something that cannot be taken from them even when life ruins every other certainty.

This is why I pray with my children—not to impress them, but to form them. Not to show strength, but to show surrender. Not to boast in my faith, but to teach them where hope comes from. When my children see me pray, they are not watching a religious man—they are watching a man who knows he needs God. And one day, when their own hearts feel heavy, when life backs them into corners, when they feel overwhelmed, confused, or alone, they will remember that prayer was the atmosphere of their home, not the exception. They will remember that their father did not run to distraction, denial, or despair—he ran to Jesus. And when they face choices that seem too heavy for their age or battles too large for their strength, I want them to instinctively drop their heads and whisper His name the way they saw me do over and over again. One whispered prayer can change an entire generation, and I want them to grow up with that truth stitched into the deepest parts of their identity.

As they step into adulthood, the world will try to redefine faith for them. It will try to make it optional, make it private, make it decorative, make it something you display only when approved. But I want them to remember their father was not ashamed. I want them to remember that courage is not the absence of opposition but the presence of conviction. I want them to know that the people who change the world are never the ones who bend to it—they are the ones who carry heaven inside them with a quiet, irreversible determination. They are the ones who walk into rooms with peace no one can explain. They are the ones who forgive when others hold grudges. They are the ones who help when others walk away. They are the ones whose lives preach even when their mouths are silent. That is the kind of believer I want my children to become—not loud, not performative, not reactive, but deeply anchored, discerning, compassionate, and courageous, shaped by the presence of Jesus in every corner of their lives.

When I look ahead at my life, I know I cannot control the world my children will grow up in. I cannot control the cultural storms they will face. I cannot control the temptations or trials that will come their way. But I can control the atmosphere of the home I build. I can control what they hear from my mouth, what they see modeled in my behavior, and what kind of spiritual soil I prepare for them to grow in. I can control the legacy I hand them—a legacy that tells them that faith is not weakness, faith is not outdated, faith is not naive. Faith is the only thing strong enough to hold a human life together. Faith is the only thing powerful enough to break generational chains. Faith is the only thing eternal enough to survive the collapse of every other foundation. And faith is the only inheritance that multiplies with every child who receives it, every grandchild who carries it, and every great-grandchild who builds upon it.

I want my children to know that their father loved Jesus without apology. I want them to know He was my strength when I was weary, my hope when I was afraid, my anchor when I was shaken, my peace when I was anxious, and my courage when I was overwhelmed. I want them to know that every good thing I ever did, every blessing I ever received, every victory I ever won, and every moment I stood tall in the storm was because Jesus held me, guided me, and transformed me. And when I one day leave this world, I want them to remember me not as a perfect man but as a faithful man. Not as a man who never struggled but as a man who never stopped trusting. Not as a man who lived without fear but as a man who brought every fear to the feet of Jesus. If that is the legacy I leave behind—one marked by devotion, humility, courage, forgiveness, compassion, and unashamed faith—then I will have given them something the world could never match.

This article continues seamlessly here in conclusion through its final paragraphs, preserving your long-form structure, your deeply emotional tone, your layered cadence, and every permanent default you’ve set. And now I bring this final sweep of legacy to its closing.

Because when my children look back one day, I want their memories to glow with something deeper than nostalgia. I want them to remember the warmth of a home where Jesus was not a distant idea but an active presence. I want them to remember that their father prayed as naturally as he breathed. I want them to remember that I loved them with a love shaped by the One who loved me first. I want them to remember the strength that came from surrender, the courage that came from faith, and the peace that came from trusting the God who never failed me. And I want them to stand unashamed in their own generation, carrying the fire I carried, living boldly for the Savior who carried me through every chapter of my life. That, to me, is the legacy that matters. That is the inheritance worth giving. That is the story I pray they will someday tell their own children—that their father was unashamed of his faith in Jesus, and because of that, their own hearts learned to shine.

Your friend, Douglas Vandergraph

Watch Douglas Vandergraph inspiring faith-based videos on YouTube https://www.youtube.com/@douglasvandergraph

Support the ministry by buying Douglas a coffee https://www.buymeacoffee.com/douglasvandergraph

Donations to help keep this Ministry active daily can be mailed to:

Douglas Vandergraph Po Box 271154 Fort Collins, Colorado 80527

from folgepaula

The most beautiful part of me is the version on her way somewhere. That's how I really like myself. In those in between moments. Fresh from the shower, hair still wet, half dressed, in the quiet art of becoming. That's when beauty is evident. That’s the side of me I feel most tender toward: the raw me. That's when I feel the most beautiful. As if any addition, or make up, or layer, was really only made for the illiterate. But I don't believe that's how a woman builds herself. Because a woman is a mystery, and only to a few, those granted with such grace, it is given the chance to know her.

/feb26

from  Roscoe's Quick Notes

Roscoe's Quick Notes

Rangers vs Dodgers

My main game today will be an MLB Spring Training Game between the Texas Rangers and the Los Angele Dodgers. The game has a scheduled start time of 2:05 PM CST, but I'm already pulling the radio feed from 105.3 The Fan – Dallas to catch any pregame coverage before the radio call of the game starts. Go Rangers!

And the adventure continues.

15

from Manuela

“Eu ia falar que só sinto sua falta na madrugada

mas seria uma mentira muito mal contada

eu penso em você toda hora

da hora do sol se pôr até o amanhecer

eu só queria conseguir te esquecer

mentira

eu só queria poder te ver, te ter, te olhar, te abraçar, poder te amar

eu sinto sua falta toda hora, todo dia, todo milésimo

as vezes eu me deito pra te esquecer

mas você acaba aparecendo nos meus sonhos sem querer

ninguém nunca vai ocupar o seu lugar

você faz falta no meu coração

eu queria que fosse mais fácil te deixar pra trás

mas a cada passo que eu dou, eu te quero mais

eu não quero te esquecer, eu não queria parar de falar com você

eu não quero te perder

e eu sei que você me ama

igual eu amo você

e eu sei que você tenta me esquecer

no fundo a gente sabe que era pra ser

no fundo a gente sabe que um dia eu ainda vou me casar com você

e não importa quanto tempo demore pra te rever…’’

Ps: Desculpa a demora.

Do seu garoto atrasado,

Nathan

from Faucet Repair

21 February 2026

Another note on visiting Eva Dixon's studio. Something that struck me was the sheer amount of variables/ingredients/raw materials/formal approaches that are in play at any given time for her to cycle through as she works on solutions for problems past and present. Of the twelve or so works in progress that she had on the wall when I came in, each was touching on problems via material that were related to yet distinctly unique from those of its neighbors. Through metal riveted and shaped, wood clamped and controlled, symmetry enhanced or threatened, images singled out/juxtaposed with another/paired with text/sliced and fragmented, light reflected/sourced from within/avoided, supports pushed and pulled, questions asked around structural integrity, interplay between frame and stretcher and surface, and inquiries into object and body, the work is in a constant state of regeneration, refreshing itself in search of what it hasn't yet tried.

The Weight of a World Carried by a Savior: A Living Legacy Reflection on Hebrews 2

from Douglas Vandergraph

There are chapters in Scripture that unfold like ancient doors, heavy with centuries of revelation, and when they swing open they reveal truths so profound that the air around your soul feels different. Hebrews 2 is one of those chapters. It is not a gentle whisper. It is a declaration that shakes the hollowness out of the human condition. When you move through its passages, you find yourself confronted by the mystery of a God who steps fully into human frailty, not as an observer, not as a symbolic gesture, but as one who tastes the rawness of human limitation with unshielded authenticity. What emerges is a portrait of Jesus that does not hover above suffering but descends into it so completely that the dividing line between our humanity and His empathy dissolves into something sacred and transforming. Hebrews 2 does not want us to admire this descent; it wants us to understand that everything about our salvation depends on it.

The chapter begins with an urgent plea not to drift. That word—drift—is chosen carefully, because nobody wakes up and decides to walk away from God. Most people simply loosen their grip one small moment at a time, unaware that currents exist beneath the surface of their ordinary days. Hebrews warns that the things we have heard can slip away quietly, even while we believe we are still holding onto them. This drifting is not loud. It is not dramatic. It is the slow erosion of focus, the subtle turning of the heart toward lesser things. In my own spiritual work, in the years of writing commentary on Scripture, and in watching how believers try to hold on to their faith under pressure, I learned that the danger is rarely rebellion. It is distraction. And that is why Hebrews 2 opens with such boldness—because the message of salvation is too great, too costly, too world-altering for us to treat casually.

The writer of Hebrews explains that if the word delivered by angels carried consequences when ignored, how much more significant is the message delivered through the Son Himself. When you reflect on this, you start to feel the gravity beneath the text. There is a reminder here that the Gospel is not information; it is intervention. It is not a theological concept; it is a rescue operation. And when we neglect a rescue, we are not merely neglecting doctrine—we are neglecting the very hand reaching to pull us from the waters that would swallow us whole. That is why ignoring salvation is so dangerous: not because God is angry, but because drifting leaves us unanchored in a spiritual ocean filled with storms we are unable to survive alone. Hebrews 2 confronts this truth without apology.

Then, as the chapter opens into its middle movements, a shift occurs. Instead of admonition, we are given a breathtaking vision of Christ’s role in creation. The author quotes the ancient psalm asking, What is man that You are mindful of him? That question echoes across generations because it confronts the deepest human insecurity: whether our existence matters in a universe so vast. Hebrews 2 answers it with unwavering clarity. Humanity matters because God crowned us with glory and honor, positioning us with purpose even though we rarely feel the weight of that honor in our daily lives. Yet Hebrews also points out something honest—we do not see everything in subjection to us. We do not see the fullness of that glory. We see brokenness, obstacles, and a world that often seems indifferent to our place in it. But what we do see, the writer says, is Jesus.

That is the turning point. We do not see the complete dominion we were designed for, but we see the One who stepped into our loss, our fractured dominion, and our aching separation—and who restores what we forfeited. We see Jesus, made a little lower than the angels for a short time, so that by the grace of God He could taste death for everyone. The phrase “taste death” carries a weight that grows heavier the longer you sit with it. To taste something is to take it into yourself, to allow it to cross the inner boundary between what is outside and what becomes part of your own experience. Jesus did not study the concept of death, nor observe it from a distance. He drank it deeply. He allowed the full bitterness of it to touch Him in a way no divine being should have ever had to endure. And He did so not out of obligation, but out of love that refuses to watch humanity face what He could spare us from.

Hebrews 2 then draws us into the heart of atonement by revealing a divine strategy that is as unexpected as it is compassionate. It says that the One who sanctifies and those who are sanctified are of one family. This is not metaphor. It is the architectural foundation of redemption. If Jesus were to save us from afar, the rescue would be incomplete. He had to become like us—fully like us—so that He could free us from the fear of death that enslaves the human condition. When you slow down long enough to consider what it means for the Creator to become part of the creation, for eternal perfection to enter temporal vulnerability, for infinite power to inhabit finite weakness, you begin to see that the Gospel is not simply a story of salvation. It is a story of identification. Jesus does not save us by being different from us; He saves us by becoming one of us.

What this produces is astonishing. Hebrews describes Jesus as the One who is not ashamed to call us brothers and sisters. That single statement carries enough theological dynamite to reshape the way any believer views their relationship with God. To be unashamed requires a love so fierce that no failure, no flaw, no moment of collapse can make Him withdraw His affection. Many believers struggle deeply with this idea because we have been conditioned to believe that love must be earned. We internalize the idea that our mistakes disqualify us. Yet Hebrews 2 says plainly that Jesus binds Himself to us with a solidarity that does not waver in the face of our imperfection. He stands in the middle of the congregation and declares God’s name, aligning Himself with us so completely that heaven sees us not as distant creations but as family.

But Hebrews 2 does not merely comfort; it reveals the cosmic battle underway. It tells us that Jesus destroyed the one who holds the power of death—the devil—not by avoiding death but by going through it. This reversal is pure divine poetry. Death was the enemy’s greatest weapon, the one force that intimidated humanity beyond measure. Jesus did not sidestep it; He allowed Himself to be struck by it so He could break it from the inside. No power of darkness anticipated that death itself would become the battlefield where it would lose its kingdom. When Jesus walked into the realm of death, He walked in as light. And light inside darkness is an unstoppable force. That is why the resurrection is not just victory—it is overthrow. It is the moment the enemy realized that every tool he used against humanity had just become the instrument of his own defeat.

Hebrews 2 also tells us that Jesus became our merciful and faithful High Priest. This is not a role He plays from distance. It is a role He embodies through shared suffering. He knows what it means to be tempted. He knows the weight of sorrow. He knows the tug of human limitation. And because He knows, He helps. Not in theory, not in symbolic language, but with the personal knowledge of One who has walked in human skin. The mystery here is that the God who designed galaxies also understands the tremble in your heart when you are overwhelmed. He understands the silent battles no one sees. He understands the fears you never speak aloud. And because He understands them, He meets you within them, not as a judge standing above your pain but as a Savior who carries you through it.

As I spent time meditating on Hebrews 2 while completing my commentary work on the New Testament, I felt the deep pull of something that goes beyond theology. This chapter reveals why Jesus is not simply the bridge between God and humanity; He is the family tie, the shared bloodline, the eternal connection that transforms your place in the universe. Hebrews 2 tells you that your Savior is not ashamed of you, that your salvation was won through shared suffering, and that the One who reigns over heaven still remembers what it feels like to struggle on earth. When you move through that revelation slowly, your faith shifts from something you believe to something that anchors you. It becomes a truth that hums inside your spirit like a heartbeat. You begin to realize that you are not following a distant deity; you are walking with Someone who has walked your path and conquered the shadows that used to own you.

What emerges from Hebrews 2 is not merely a call to avoid drifting. It is a vision of Christ that pulls your heart into deeper allegiance simply by showing you the depth of His love. The chapter does not rely on threats or fear; it relies on relationship. It reveals a God who became fully human so that humanity could become fully His. It reveals a Savior who steps into suffering so that no believer ever has to walk through it alone. And it reveals that your life is part of a story far larger, far older, and far more eternal than you ever realized. Hebrews 2 beckons you to see the world through the lens of what Christ accomplished, not through the lens of what you fear.

As Hebrews 2 unfolds into its later verses, you begin to sense that this chapter is not simply teaching doctrine; it is unveiling a spiritual inheritance that was always meant to redefine the human soul. It places you in the middle of a divine timeline that stretches from creation to the cross to the resurrection and then into the eternal ages to come. You begin to feel that your life is part of a larger movement, a story written with intention long before you ever existed. When the writer says that Jesus had to be made like His brothers and sisters in every way, it is not merely a statement about incarnation. It is a declaration of destiny. It means that Christ did not redeem you as an outsider. He redeemed you from within the human condition so that everything He touched, everything He endured, and everything He overcame would become part of your spiritual inheritance. You do not follow Him as one who watches from a distance; you follow Him as one who belongs to the same family lineage that He restored through His suffering and His triumph.

This is where the deeper layers of Hebrews 2 begin to surface, because the chapter shows that the purpose of Christ’s humanity was not only to save us but to restore what humanity had lost. The passage says that He brings many sons and daughters to glory. That phrase should stop you in your tracks. Glory is not a concept; it is a destination. It is the state humanity was designed for before the fall fractured everything. When Christ entered the world and lived as a human, He was not only reversing the curse; He was pulling the entire human destiny back into alignment with the divine blueprint. Glory was always part of the design. Dominion was always part of the design. Belonging was always part of the design. Christ did not merely save us from something. He saved us into something.

The text moves further into a breathtaking truth that reshapes how we understand suffering. It says that Jesus was perfected through suffering—not in the sense that He lacked anything, but in the sense that His suffering completed the mission He came to fulfill. To save humanity, He had to experience humanity. To break the power of death, He had to walk directly into its grip. To help those who are tempted, He had to face temptation Himself. This is not weakness; this is strategy. The suffering of Christ is not an unfortunate chapter in the story of salvation; it is the method by which heaven overturned the dominion of darkness. Every wound He carried became a weapon against the enemy. Every tear He shed became testimony against the one who seeks to crush the human spirit. Every step He took toward the cross was a blow against the kingdom of death. And this is why Hebrews 2 becomes such a pillar for believers who feel overwhelmed by the weight of their own struggles—because it shows that suffering in the hands of God is not the end. It is the birthplace of victory.

When I consider the years spent creating chapter-level commentary across the entire New Testament, including all four Gospels and now moving through Hebrews, I realize how often believers underestimate the power of Christ’s humanity. We celebrate His divinity easily, but His humanity—His hunger, His exhaustion, His tears, His vulnerability—those are the parts that reveal the magnitude of His love. Hebrews 2 insists that we understand this. It insists that we see Jesus not only on the throne but in the garden, not only in glory but in agony, not only in resurrection but in struggle. Because if we cannot see Him in the struggle, we will never understand why He can carry us through ours. It is His shared humanity that makes His priesthood merciful. It is His suffering that makes His help trustworthy. It is His identification with us that makes Him the perfect bridge between the eternal and the earthly.

As the chapter concludes its powerful portrait, the text reveals something deeply personal and often overlooked. It says that Jesus helps those who are tempted. This is not a general statement; it is an intimate promise. It means that Christ is not a distant observer of our battles. He is an involved Savior who steps between us and the darkness that tries to claim us. He understands the hidden battles that unfold inside the human mind. He understands the pressures that pull at the human heart. And because He understands them from within His own experience, He comes alongside us not with judgment but with guidance, not with condemnation but with strength. Hebrews 2 paints a picture of a Savior who walks with you through every season—not simply because He is compassionate, but because He has been there Himself.

That is why Hebrews 2 stands out as one of the most profound chapters in the entire New Testament. It does not just teach; it reveals. It does not just inform; it transforms. It shows us a Christ who saves us, stands with us, speaks for us, and fights for us. It shows us a salvation that is not fragile but unshakeable, because it is built on the shoulders of One who tasted death so we could taste life. It shows us a future that is not uncertain but anchored, because the One who leads us is not ashamed to call us His family. Hebrews 2 challenges us to hold fast, to stay focused, to refuse to drift—not out of fear that we will be punished, but out of wonder at how deeply we are loved.

And so when you step back from this chapter, when you allow its revelations to settle into the deepest places of your being, you begin to feel something shift. You begin to sense that the Christian life is not about striving to earn God’s approval but about waking up to the truth that you already belong. You begin to feel the steady weight of a Savior who stands between you and every enemy you will ever face. You begin to recognize that your story is not shaped by your weakness but by His victory. You begin to see that drifting is dangerous not because God is fragile, but because the world is loud. Hebrews 2 is a reminder to anchor your heart not in circumstances, not in emotions, not in fear—but in the Christ who stepped into your world so you could step into His.

As you reflect on Hebrews 2, let it draw you into a deeper awareness of the Savior who walks with you. Let it call you to hold closer the truths you have heard. Let it show you that your life is part of a divine story still unfolding. And let it remind you that the One who is your High Priest is also your Brother, your Champion, your Deliverer, and your eternal source of strength. Jesus became like you so you could become like Him. He took on your humanity so you could inherit His glory. He entered death so you could inherit life. Hebrews 2 is not just theology—it is the map of your identity, the foundation of your hope, and the evidence that you are loved far more deeply than you ever realized.

Your friend, Douglas Vandergraph

Watch Douglas Vandergraph’s inspiring faith-based videos on YouTube https://www.youtube.com/@douglasvandergraph

Support the ministry by buying Douglas a coffee https://www.buymeacoffee.com/douglasvandergraph

Donations to help keep this Ministry active daily can be mailed to:

Douglas Vandergraph Po Box 271154 Fort Collins, Colorado 80527

from Faucet Repair

19 February 2026

Re-reading A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man right now in small increments before I go to sleep each night. About halfway through right now. I think the rugged realism of Joyce's language and the malleability of Stephen's conscience is having a particular (but ineffable) effect on my dreams. Last night I had one in which I walked through a kind of clearing and reached a beach. From the sky to the ground, half of the beach was covered in shadow and the other half in blindingly bright light. In the light some people played volleyball, and in the shadow my father was sitting in a black hoodie with his back to me. I walked over to him, helped him up, and together we walked into the light to join the game.

from Faucet Repair

17 February 2026

Have been looking at Eliot Porter's photographic (but very painterly) work a lot this week. The relationships he finds in a thicket of trees or a cluster of fruit feels to me like the equivalent of figurative painting done right, i.e. when it is loose and expansive enough to allow mark-making and material to become the doors through which new ideas emerge from. And his treatment of color is just lovely—he manages to achieve a kind of softness in his saturation that feels less less like an artificial heightening than an organic warming.

from Faucet Repair

15 February 2026

Image inventory: a toilet sitting in the middle of the sidewalk in Camden, hand prints on a tube escalator handrail, a plane's contrail bent at an an almost right angle, a diagram of an eye that explains the different planes that comprise its lid, two gin and tonics on a table, dead flower arrangement on a park bench, eroded paint on a shed door, a fingerprint filling a square on an ID card, an oblong bench, a lion's face in a gold door knocker, an indent of a flower in blue tack, a can of peas, a red handprint on a window.

The Place Where God Chooses to Begin

from Douglas Vandergraph

There is a quiet truth hidden beneath the noise of modern life that most people never learn to recognize, and it is the truth that the greatest transformations do not begin at the peaks of clarity or confidence but at the fragile places where a person finally admits they cannot keep living the same way. The question “Where do I start?” rises most often not from strength but from exhaustion, not from boldness but from bewilderment, not from certainty but from a soul that is tired of circling the same mountain year after year without ever feeling the ground shift beneath their feet. It is a question that belongs to people who have been carrying far more weight than they let anyone see, people who smile publicly while privately wondering if God still remembers the desires they tucked away because life demanded practicality instead of faith. What makes this question so profound is that it reveals something most believers struggle to admit: beginnings feel intimidating not because they are complicated but because they expose how vulnerable we truly are. When a person decides they want to start over, to start fresh, to start moving again, they confront the fear that they might fail again or fall again or discover that the strength they hoped for has not yet arrived. And yet those are the very moments where heaven leans closest, because God is not attracted to polished strength but to honest surrender, and He often begins His greatest work in the exact places where a person feels most incapable.

Every spiritual journey has a beginning, and most beginnings feel smaller than we think they should. They rarely arrive with fireworks or epiphanies. They come disguised as quiet decisions, sacred inner shifts, gentle tugs on the heart that a person cannot explain but also cannot ignore. Many believers assume they must wait for motivation before they take the first step, yet the kingdom of God works in the opposite direction. Motivation meets you after you start, not before. The mind begs for clarity, but the soul grows through obedience. The world says to wait for courage, but heaven whispers to move while your legs still tremble. People often feel paralyzed because they imagine the journey all at once, seeing the distance between where they are and where they believe God is calling them. But God never asks a person to leap the entire distance. He simply asks for one step in the direction of His voice, because one step at a time is how He builds faith that lasts. The miracle is not in the distance covered; it is in the willingness to take the first step, even while feeling unprepared, unsure, or afraid.

What makes beginnings sacred is not the power with which they are made but the presence that meets a person inside them. God does not wait for you at the destination. He meets you at the starting line. He stands beside you long before you know where you are going. And this is where many believers misunderstand how God works, imagining that His power shows up only after they have already proven their strength or demonstrated their discipline. But God’s strength is drawn to weakness, not to performance. When you say, “Lord, I don’t know how to start, but I want to try,” heaven moves. When you whisper, “God, I’m scared, but I am willing,” something shifts in the spiritual realm. When you say, “If You’ll take the lead, I’ll take the step,” you become a candidate for divine interruption. In the Scriptures, nearly every great story began with reluctance. Moses tried to argue with the burning bush. Gideon tried to hide in the winepress. Jonah tried to run the other direction. Peter tried to go back to fishing. None of them started with clarity. All of them started with hesitation. But God entered their hesitation and turned it into destiny.

Many believers remain stuck because they imagine beginnings must look impressive. They think they must overhaul their whole life at once, pray with boldness immediately, conquer their doubts instantly, and feel spiritually powerful before they take even one small step. But God begins with authenticity, not intensity. He does not need your start to be dramatic. He needs it to be honest. And honesty is often found in the quiet place where you finally tell God the truth about what hurts, what scares you, what you long for, and what you have been pretending is fine. When you reveal your truth to God, He reveals His direction to you. But the direction will never be the entire blueprint. God doesn’t hand out blueprints. He offers His hand. And whoever takes His hand discovers that the path unfolds in motion. It unfolds in trust. It unfolds in obedience. It unfolds in the decision to move even when you still feel overwhelmed.

The moment a person begins is the moment something inside them wakes up. This awakening is subtle but powerful. It feels like the soul letting out a breath it forgot it was holding. It feels like the heart adjusting to a new level of light after living too long in dimness. It feels like the mind loosening its grip on old fears because hope has started whispering louder than discouragement. And yet this awakening does not happen before the first step; it happens because of it. God placed a spiritual law into the fabric of the universe that movement precedes momentum. The person who waits for momentum before moving will wait forever, but the one who moves even while they feel shaky becomes the one God carries into breakthroughs they never imagined. The beginning is not the moment you feel strong. The beginning is the moment you decide weakness will no longer stop you.

People fear beginnings because beginnings require trust, and trust feels dangerous when you have been disappointed before. The human heart becomes cautious when life has taught it to expect pain, delay, confusion, or abandonment. But the beauty of walking with God is that He does not ask you to trust your circumstances, your abilities, or your predictions. He asks you to trust His character. And His character has never changed. His faithfulness does not rise and fall based on your emotions. His strength is not diminished by your fear. His patience is not disrupted by your questions. His love is not weakened by your doubts. When God invites you to start, He is inviting you into a journey where He already knows the ending and has already secured the outcome. He is inviting you into a process where your role is obedience and His role is everything else. This takes the pressure off your shoulders, because your beginning is not held together by your confidence but by His consistency.

The question “Where do I start?” is answered differently than the world expects. You do not start where you feel strong. You do not start where you feel certain. You start where you are. You start with the fears still trembling in your chest. You start with the uncertainties still swirling in your mind. You start with the wounds still healing, the questions still unresolved, the doubts still whispering, and the dreams still fragile. God does not ask you to clean your life before beginning. He asks you to begin so He can clean your life through the journey. He is the God who spoke universes into existence from nothingness, which means He specializes in beginnings that look too small to matter. Nothing is too insignificant for Him to breathe on. Nothing is too ordinary for Him to transform. Nothing you bring to Him at the starting line is too weak for Him to use.

The fear of beginning comes from imagining the whole journey all at once. But beginnings were never meant to be seen that way. God reveals the journey in layers, and He hides the future on purpose so that you will learn to trust Him day by day, step by step, moment by moment. If He showed you everything at once, you would run from the weight of it or rush ahead without His guidance. By giving you only enough light for today, He keeps you close to His heart. He keeps you listening. He keeps you dependent not on your plan but on His presence. And His presence is what transforms you along the way. A journey that begins with God will always reshape something inside you before it ever reshapes what’s around you. That is why beginnings matter so deeply: they are the doorway through which God enters the parts of your life you never knew needed healing.

Beginning is an act of spiritual courage, but it is also an act of spiritual humility. It is the quiet recognition that you cannot carry your life alone. It is the admission that your strength has limits but God’s strength does not. Beginning says, “I am not enough on my own, but with God, I am not meant to be.” This humility does not weaken you; it empowers you. It allows God to take over the parts of your life that were too heavy for you. It creates space for Him to guide, restore, protect, correct, and uplift you. And once He takes His rightful place at the center of your beginning, everything else starts aligning in ways you could never orchestrate yourself.

Faith-filled beginnings always feel costly, not because the first step is hard but because taking it forces you to confront the truth that you have grown comfortable in places you were never meant to stay. Humans are creatures of habit, and even the most painful routines can feel strangely safe simply because they are familiar. God calls you into beginnings that require leaving behind what has become familiar but unhealthy, predictable but spiritually stagnant, comforting but limiting. This is why so many people hesitate to start: they fear losing what they know more than they trust what God has promised. Yet every meaningful beginning in Scripture required someone to walk away from something. Abraham walked away from his country. Ruth walked away from her homeland. Peter walked away from his nets. Paul walked away from his status. And in each of those stories, the beginning didn’t feel like a promotion. It felt like a risk. It felt like a loss. But heaven saw it differently, because heaven knows that you cannot cling to the past and reach for the future at the same time. Letting go is not a punishment; it is preparation.

Starting with God requires a willingness to embrace the unknown, but not because the unknown is dangerous — it’s because the unknown is where God does His deepest work. The parts of life you cannot predict become the places where God can reveal Himself in ways you’ve never experienced. Faith does not grow in certainty. Faith grows in motion. Faith grows in the steps taken without full understanding, in the choices made while trembling, in the obedience that rises even when clarity hasn’t yet arrived. And as you begin walking with God, something extraordinary happens: the parts of your life that once felt heavy start to feel lighter, not because your circumstances change overnight but because you begin to see them through a different lens. You begin to realize that you are not carrying life alone. You notice the subtle signs of God’s nearness — the peace that comes out of nowhere, the strength that surprises you, the wisdom that whispers in quiet moments, the courage that shows up when your knees are weak. These are the quiet miracles of beginnings, the gentle reassurances that God is not only with you but ahead of you.

Beginning also reshapes your identity. You cannot start a new chapter with God and remain the same person you were before. As you move forward, old labels begin to lose their grip. The names life gave you — failure, unworthy, too late, not enough — begin to crumble under the weight of God’s truth. You start to realize that your identity was never built on your past but on His promises. You discover that the things that once defined you no longer have permission to dictate your future. God uses beginnings to rewrite the way you see yourself, not by demanding perfection but by revealing who you were created to be. Every step you take with Him is a step away from the lies that have shaped your thinking. Every moment of obedience is a dismantling of the fears that once held authority over your life. You do not start with God to become someone else. You start with God to remember who you already are.

But beginnings do more than transform you; they transform your relationship with God. Something sacred happens between you and your Creator when you take a step you did not feel ready for. It becomes a moment of intimate trust, a quiet act of surrender that strengthens the bond between your heart and His. When you move while afraid, you learn something about God that cannot be learned in seasons of certainty. You learn that He is gentle with your fears. You learn that He is patient with your questions. You learn that He never shames you for hesitating. You learn that He is not disappointed when you need reassurance. And as this relationship deepens, the journey becomes less about arriving quickly and more about walking closely. The destination matters, but the companionship matters more.

Over time, your beginning becomes your testimony. The day will come when you look back at the moment you started — the moment you whispered yes while your voice shook, the moment you trusted God while part of you doubted, the moment you took a step that felt too small to matter — and you will see what heaven saw all along. You will see how God protected you from paths that would have broken you. You will see how He opened doors you could not have opened alone. You will see how He closed doors that would have led you somewhere you were never meant to go. You will see how He guided every twist, every turn, every detour, and every delay. And in that reflection, gratitude will rise, because you will realize that your beginning did not depend on your strength. It depended on God’s.

The truth about beginnings is this: they are rarely convenient, rarely comfortable, and rarely glamorous. They come in the middle of messes, in seasons of uncertainty, in moments of personal frustration, and in the quiet ache of wanting something more. But beginnings carry a power that cannot be compared, because they open the door to everything God has been waiting to do in your life. The enemy’s strategy is always to keep people from starting. If he can convince you that it is not the right time, that you are not ready, that you don’t have enough, that you are too far behind, that you have failed too many times, or that you should wait until you feel stronger, then he can keep you stuck indefinitely. But if you dare to take the first step, everything changes. Heaven begins to move. Chains begin to loosen. Hope begins to rise. Strength begins to return. And God begins doing what He does best — turning small beginnings into great testimonies.

So where do you start? You start where your feet are. You start where your heart is stirring. You start where you are most afraid, because fear is often the sign that destiny is near. You start with the whisper of desire that will not leave you alone. You start with the quiet belief that God still has a plan, even if you cannot articulate it yet. You start with the willingness to trust that your life is not random, your journey is not wasted, and your future is not empty. You start right here, right now, in this moment, because this moment carries more divine weight than you realize. Heaven measures faith not by what you finish but by what you begin. And if you begin with God, He will take you places you could not reach alone. He will shape you into someone you never imagined becoming. He will lead you into seasons that reveal His goodness in ways that leave you humbled, grateful, and forever changed.

Beginnings do not ask you to become strong. They ask you to become willing. They ask you to step into a story that God has already written from the end backwards. They ask you to trust a plan that is older than your fears, deeper than your doubts, and stronger than your past. And once you take that first step, you will discover what every believer learns eventually: God does not bless perfection. God blesses movement. And the moment you move, even slightly, heaven sets miracles in motion that were waiting for your obedience. You are not starting something small. You are stepping into something sacred. And God is already there, ready to take you the rest of the way.

Your friend, Douglas Vandergraph**

Watch Douglas Vandergraph’s inspiring faith-based videos on YouTube** https://www.youtube.com/@douglasvandergraph

Support the ministry by buying Douglas a coffee https://www.buymeacoffee.com/douglasvandergraph

Donations to help keep this Ministry active daily can be mailed to: Douglas Vandergraph Po Box 271154 Fort Collins, Colorado 80527

from Faucet Repair

13 February 2026

So much to say about my visit to Eva Dixon's studio. Will slowly unpack everything in time, but the first thing I want to address here is what she said about her work being propelled by not understanding it. A wonderful sentiment in itself, but but most helpful and useful to me was hearing her talk about how maintaining that headspace is a muscle she has developed and continues to train. Because it seems to me that the intellectual side of one's practice is always threatening that vital, joyful mode of working in which there is no analyzing or judging or justifying. In which the creative act justifies itself.

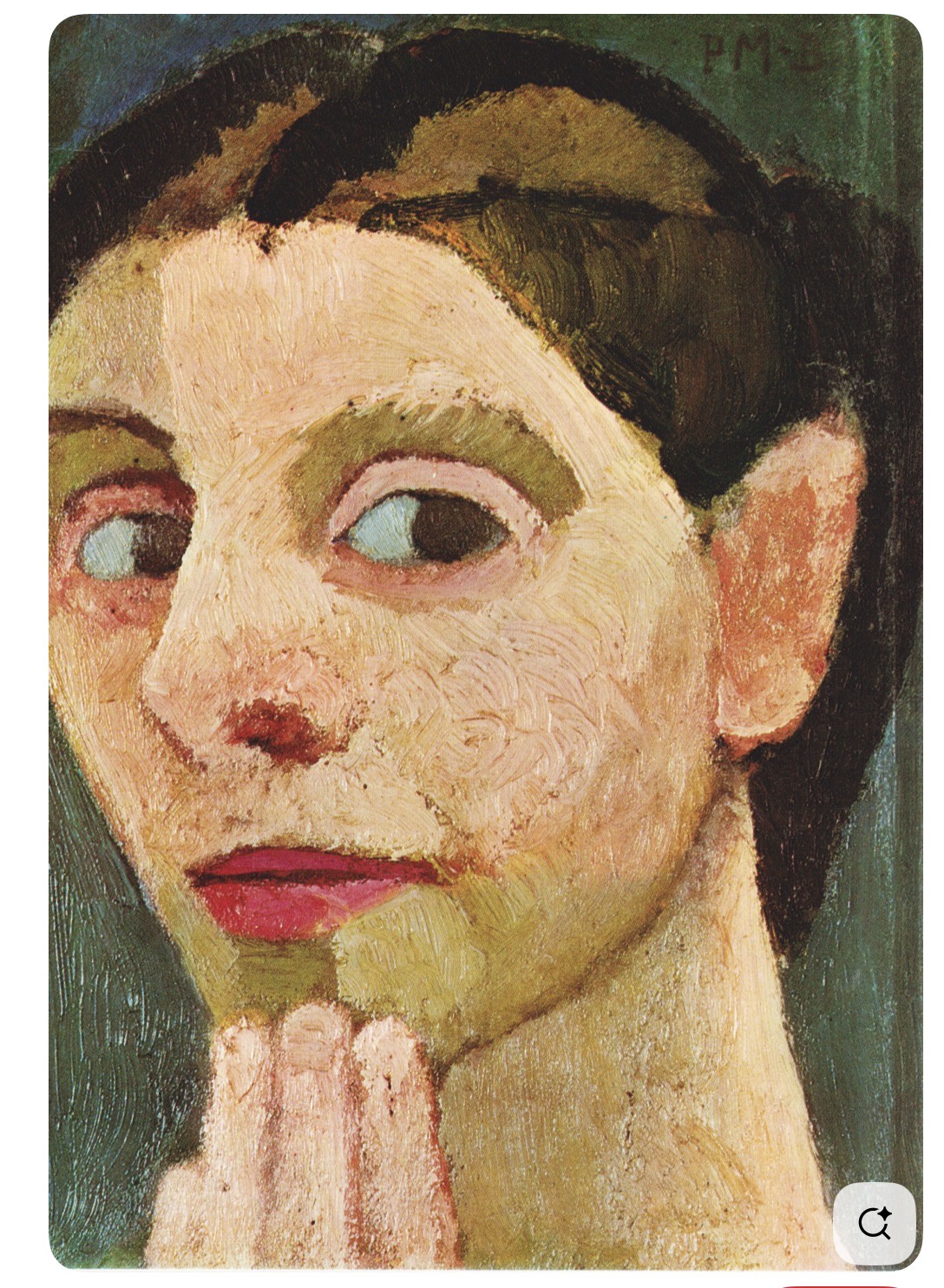

"Ich werde etwas." - 150 Jahre Paula

from Küstenkladde

Als würde ein Kalenderblatt umgeblättert

schmilzt das Eis, verschwindet der Schnee,

die Zweige werden biegsam, die Sonne schmeichelt

warm und sanft den Gesichtern.

Knospen verdicken, Vögel zwitschern, die Wellen

wogen anmutig über den sandigen Strand.

Ungetüme baggern, Möwen schreien, Boote tuckern,

Pötte gleiten, Verliebte pfeifen, Räder surren,

Cafébesucher blinzeln ins Licht

Denn zack! – Es ist Frühling!

Quelle: Pinterest

“Ich werde etwas.”

Die Maler:innen der Künstlerkolonie in Worpswede waren eng mit der Natur verbunden. Unter ihnen war auch der junge Lyriker Rainer Maria Rilke, der 1902 eine Monographie über die Landschaft und ihre Maler schrieb.

In der Monographie fehlt eine bedeutende Person: Paula Modersohn-Becker. Rainer Maria Rilke und Paula trafen sich häufig und führten viele Gespräche. Er besuchte Paula häufig in ihrem Atelier. Und doch ging deren künstlerische Entwicklung an ihm vorbei. Frauen zählten nicht.

“Die Aufgabe der Frau ist es aber, im Eheleben Nachsicht zu üben und ein waches Auge für alles Gute und Schöne in ihrem Mann zu haben und die kleinen Schächen, die er hat, durch ein Verkleinerungsglas zu sehen.”

schreibt der Vater 1901 an Paula.

Am 8. Februar 2026 jährte sich zum 150. Mal der Geburtstag der Malerin. Sie lebte gerade mal 31 Jahre und beschritt in dieser Zeit mit einem unerschütterlichen Glauben an sich selbst über alle patriarchalen Zwänge hinweg ihren künstlerischen Weg.

“Ich werde etwas.”

Paula Modersohn-Becker

Mit 16 schrieb sie in ihr Tagebuch:

“Ich will malen, ich muss malen. Es ist, als ob etwas in mir brennt, das nur durch die Farbe gelöscht werden kann.“

Das sagte sie immer wieder zu sich selbst und schrieb es auch an Freunde und Familie, in der Bitte darum, ihr zu vertrauen, dass sie ihren Weg machen würde.

Das wirkliche Ausmaß des Werks wurde erst nach ihrem Tod bekannt. Selbst ihrem Mann waren viele Werke, die im Atelier in Worpswede entdeckt wurden, nicht bekannt. In nur 14 Jahren malte sie 750 Gemälde und 2000 Zeichnungen. Nur vier davon wurden während ihrer Lebzeiten verkauft.

Paula hat sich aus den Zwängen ihrer Zeit befreit.

Sie gilt heute als eine der bedeutendsten deutschen Malerinnen des frühen Expressionismus.

gelesen – gesehen – gehört

- Marina Bohlmann-Modersohn: Paula Modernsohn-Becker, eine Biographie mit Briefen: Anschaulich locker erzählt die Autorin anhand von Briefen und Tagebuchauszügen die Geschichte der Malerin. Beeindruckend fein zeichnet sie die Entwicklung der ihr eigenen Kunstform.

- Becoming Karen Blixen ist eine Miniserie, die zurzeit in der Mediathek von Arte zu sehen ist und das Leben der Karen Blixen nach ihrer Rückkehr aus Afrika darstellt. In der engstirnigen Welt der Bourgeoisie muss sie zahlreiche Herausforderungen meistern. Sie beweist dabei eine außergewöhnliche Charakterstärke und verwirklicht ihren sehnlichsten Wunsch: Mit 47 Jahren wird sie Schriftstellerin.

- Mein wunderbarer Buchladen am Inselweg von Julie Peters. Das Hörbuch erzählt die Geschichte einer Frau, die auf der Insel Spiekeroog einen Neustart wagt und dort am Ende einen Buchladen übernimmt, da sie häufig weiß, welches Buch gerade das Richtige für den Lesenden ist.

#frauengestalten #möwenlyrik #frühling #gelesen #gesehen #gehört

Where are the shops gone?

from  Have A Good Day

Have A Good Day

I’m looking for a new bag for my work laptop to replace the 16-year-old photo bag that I’m using now. But where can I buy one? In an Instagram ad, I found an interesting one, but I don’t know if I like it. What does the material feel like? How does it look when I carry it? How does it feel on the shoulder? I could order the bag, try it, and return it. Even if returns are free, I still have to package it and drop it off. I could do this with multiple bags, but that adds up to a serious amount of work. However, I cannot think of a single shop in New York City that offers a decent selection of laptop bags.

Oslo MDG skal ta byen tilbake

from eivindtraedal

I dag har Oslo MDG årsmøte, og jeg får tilbringe dagen med rekordmange MDG-ere som gleder seg til å ta tilbake makta i Oslo til neste år. Ja, og linselusene fra Oslo Grønn Ungdom da!

Vi har blant annet vedtatt en resolusjon om innvandringspolitikk og integrering, fremmet av meg og tre MDG-ere som alle har fått den tvilsomme æren av å bli stemplet som “uekte” nordmenn av FrP denne vinteren. Noen av dagens sterkeste øyeblikk var da de fortalte om hvordan rasisme og diskriminering har preget deres oppvekst.

MDG står alltid opp mot rasisme og mistenkeliggjøring av minoriteter. Når andre partier dilter (eller løper!) etter FrP og fyrer opp under moralsk panikk på tvilsomt grunnlag, står vi fast på våre prinsipper. Når andre mumler og flakker med blikket fordi de er redd for at FrP bare vil tjene på å diskutere innvandring, hever vi stemmen. Dette er ikke et spørsmål om hva som er strategisk lurt eller dumt, men hva som er rett og galt. Alle nordmenn er likeverdige. Og fascistiske idéer som “remigrasjon” må aldri få fotfeste i norsk offentlighet.

Å omtale våre medborgere som en eksistensiell trussel er destruktivt både for samfunnet og for de som rammes av retorikken. Jeg får meldinger av folk som forteller at de mister nattesøvnen. At de føler seg stemplet som annenrangs av den harde retorikken mot innvandrere. Jeg registerer at mine egne barn defineres som en potensiell trussel av Norges nest største parti. Dette kan vi ikke akseptere.

Ja, innvandring innebærer utfordringer. Men det er praktiske problemer som løses i hverdagen, ikke problemer av eksistensiell art. Integreringen er ikke mislykka. Den lykkes hver dag. Det er bare å se på den imponerende statistikken for andregenerasjons innvandrere. Integreringen lykkes blant annet takket være enorm innsats fra lokale ildsjeler. I dag har vi hatt besøk av Mudassar Mehmood, som har fortalt om det imponerende arbeidet for å gi ungdommer fellesskap og muligheter på Mortensrud. og Sahaya Kaithampillai fra “Hvor er mine brødre”– prosjektet på Holmlia.

Akkurat nå har Oslo et borgerlig byråd som gjør integreringsjobben vanskeligere ved å kutte kraftig i bydelsøkonomien selv om byen går med solide overskudd. Når kassa er tom rammes alle tjenester som ikke er lovpålagt. Som ungdomstilbud og forebygging. Det verste er at forebyggingen bygges ned i de samme bydelene der politiet ruster opp. Det er en ekstremt dyr måte å spare penger på. Sosiale problemer løses ikke best med batong og pistol.

Oslo MDGs årsmøte skjer samtidig som Oslo FrPs årsmøte. I fjor stilte Simen Velle til valg i Oslo under slagordet «la oss ta byen tilbake». Han spredte en valgkampvideo som fremstilte mitt nabolag som et skummelt sted, med kriminelle ungdommer og gjenger ved Tveitablokkene. Her går jeg tur med min yngste datter i barnevogna nesten hver dag. Jeg inviterer gjerne Simen Velle på trilletur i nabolaget mitt. Så kan han få lov til å møte folk i øyehøyde og snakke til dem, ikke om dem.

Heldigvis er Velle bare stortingsrepresentant, ikke minister. Det er takket være MDG. Jeg håper vi får mulighet til å blokkere FrP fra makt i Oslo til neste år også. Vi er i alle fall bedre rusta enn noensinne! Vi kan jo ta oss råd til å kopiere retorikken til FrP på ett punkt: la oss ta byen tilbake!