Want to join in? Respond to our weekly writing prompts, open to everyone.

from Typical girl not so typical life

This is my story about dealing with chronic pain. I did not expect to suddenly have a massive pain in my backside, literally. I found out about 2 years ago that I have a “rare” condition called Bertolotti's syndrome. Bertolottis or BS for short, which seems appropriate now, is a a congenital condition that causes chronic lower back pain due to an abnormal connection or extra bone between the sacrum and the last lumbar vertebra.

At first I thought my back pain was due to an incident in secondary school (Ireland) where a student knocked into me during a game of indoor rounders. I was positioned with my knee bent forward and collided body first. After falling back flat on the floor and not moving for at least 5 minutes I started to feel a pain in my neck. This went on to develop into lower back pain where I went to see a physiotherapist and was told my hip joint was out of place. I continued to receive treatment three times a week then two times a week to twice a month or so. This continued for a while, I tried pirates, exercises, all the usual recommendations. I still don't know if my current situation relates to this incident but its part of the story.

Fast forward to 2 years ago, about 10 years later. I'm living in Scotland and consult my GP about ongoing lower back pain. I'm given anti inflammatories and sent on my way. After the first round I'm given another. I get a referral to physiotherapy where the physiotherapist prods my back to the point where tears are flowing into the pillow. Then I'm told to do a specific set of exercises. I do what I'm told, trusting a professional to no resolve. I continue to pester the GP, given different pain relief and being told by one doctor that the pain is in my head, described as phantom pain. I actually believed them, who wouldn't right, you're told by someone who has gone through the works of training and has a degree in the profession, why would you feel you could question it. Until it all becomes to much and your personal and professional life starts to suffer.

Finally I get scans done and think yes this is going somewhere but no, nothing looks abnormal. They prescribed stronger pain killers, tramadol, you take it and suffer side effects such as naseau, dizziness, and headaches but you endure. You finally get a referral to pain management but guess what, the waiting list is over a year. In the meantime, you get prescribed gabapentin. Gabapentin was explained to me as a drug that used to treat depression and is now used for nerve pain. When googled how it can feel to be on this drug this is what you get, reminiscent of alcohol intoxication or opioid-induced euphoria. Trust me, it does not feel like this, after several months I start to think I'm going insane, I start losing short term memory, have brain fog, and become confused.

Eventually, I get my appointment with the pain specialist. Within 5 minutes the doctor points out an abnormality on my spinal xray and explains I have what's called Bertolotti's Syndrome. The next steps are steroid injections and they explain i must go through 3 procedures before even considering a surgical option.

Don't get me wrong I haven't done extensive research into this condition and don't know all the facts, but from what I have learned, the reason Bertolotti's is so “rare” is that it is so undiagnosed. It is passed off as many other reasons, conditions, or you're told it's in your head.

The reality of all of this is your first, second, even third procedure may not work and in the meantime you're on 15mg Butec patches and you're being scrutinised at work after putting in several years of high standard work and continual progression and now have to look at more suitable options for career choices after spending a third of your life working towards something you thought could be your future.

The point of this blog is not to gain sympathy, it's not to be apologised to by those who don't understand or have the capacity to sympathise with you but to share the struggle of living with a condition that can't always be seen on the outside. You show up, you try your best, you don't justify your pain and yet you're let down, by professionals, by friends, colleagues, managers. You're expected to find a way to continue. To stand up. To fight your own battle.

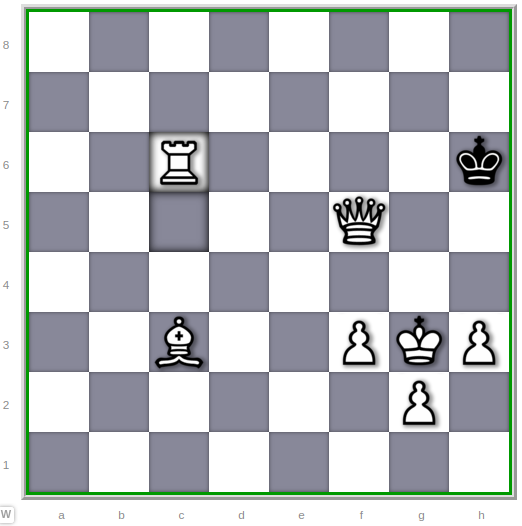

Rook-Queen-Bishop Combination Checkmate

from  Roscoe's Quick Notes

Roscoe's Quick Notes

I won this club-based correspondence chess tournament game a few days ago with the Rook, Queen, Bishop Combination Checkmate seen above. The full move record of this game: 1. d4 d5 2. h3 Nf6 3. e3 e6 4. a3 a6 5. Nd2 c6 6. c4 g6 7. Ngf3 h6 8. cxd5 Nxd5 9. Bd3 Bg7 10. Ne5 Bxe5 11. O-O Nd7 12. dxe5 Nxe5 13. Nc4 Nxc4 14. Bxc4 Nxe3 15. Bxe3 Qxd1 16. Rfxd1 O-O 17. Bxh6 Re8 18. Bf4 b5 19. Bb3 Bb7 20. Rd7 Rab8 21. Rad1 Rbd8 22. Bc7 Rxd7 23. Rxd7 c5 24. Be5 Bc6 25. Rd6 Bd5 26. Bxd5 exd5 27. Rxd5 f6 28. Bxf6 Re1+ 29. Kh2 c4 30. Bc3 Re2 31. f3 Kh7 32. Rd7+ Kh6 33. Rd6 Kh5 34. Rxa6 g5 35. Rb6 b4 36. Rxb4 Kh4 37. Rxc4+ Kh5 38. Kg3 Re3 39. a4 Re8 40. Kh2 Re2 41. Rc5 Kh4 42. Bf6 Rxb2 43. Bxg5+ Kh5 44. Kg3 Rb4 45. Bd2+ Kg6 46. Bxb4 Kf6 47. a5 Ke6 48. a6 Kd6 49. a7 Kd7 50. a8=Q Kd6 51. Qd8+ Ke6 52. Bc3 Kf7 53. Qd7+ Kg6 54. Qf5+ Kh6 55. Rc6# 1-0

And the adventure continues.

Duality of life itself 🇫🇷⚜️🇫🇷⚜️

from  The happy place

The happy place

Hello I wanted so badly to write about the soup I had for dinner today!

Soup is a category of food which I typically don’t eat, but I have changed a lot lately, and I savour the opportunity to familiarise myself with myself again, and in so doing I have discovered and renewed my appreciation for soup.

There’s a bakery nearby. A French one 🇫🇷⚜️🇫🇷⚜️

I understand why many people love France and the iconic Count of Monte Christo, and the also iconic Eiffel tower, and that even though some fools have built higher towers elsewhere, they are mere copies.

They make levain beads in there, in the bakery: real French bread and baguette. Levian baguette which I can buy on my way home for lunch, and then I can just heat up some soup and eat like a king.

If you picture this, it’s easy to understand what a privilege it is to have what is a small portal to France just next block, where you could even get a croissant.

So back to the soup, I had one today which was very funny, because it was a type of Mexican soup which looked just like vomit.

Just like vomit.

With this rich thought in my head I went out into the evening darkness. There wasn’t one single star visible, and the cold autumn rain felt cold on my skin.

For whatever reason, a smell of sewage filled the crisp air, an overflowing septic tank somewhere? As I walked along the streetlights, past the bakery and onwards into the night I had a strong feeling of thankfulness for this beautiful world with soup and France, and a lump in my throat, a feeling of maybe having opened an old wound.

A feeling, maybe of sewage, or of vomit?

A release which stings the eyes. A strange duality of life.

flowers || 8 oct

from Notes I Won’t Reread

I’ve always hated flowers.

Not the small, polite kind of hate, No i mean the kind that sits deep in your chest and makes your skin crawl just looking at them. I hate their smell, their look, their softness, their lies. I hate the way people smile at them like they’re something pure. They’re not. Thy’re parasites dressed in color, pretty corpses, dying slowly and pretending its beautiful.

People always say flowers make things better. “they bring life”. They say, they dont, they never do, They’re dying the second you cut them, You tear them from the ground, stick them in water, and call that love? , its not love, its decoration, you might as well hang a noose and call it a necklace.

When my mother died, the house was drowned in flowers. Every table, every chair, every corner was covered in bouquets, sympathy cards, fake comfort. The air was thick, too sweet too warm like it was choking me, You couldn’t take a breath without tasting perfume and death mixed together. I didn’t really see most of it. I spent half my time in the basement, hiding from my father’s fists and words. But I could smell it. Oh, I could smell it. That sweet, suffocating perfume curling up through the cracks of the floorboards. The flowers were everywhere, and I was down there, smelling them, thinking about how they had the audacity to exist while I was invisible, while my life was being bruised and beaten and ignored. And as thir petals started to fall, I remember thinking “good. Let them die too” .

But my hate didnt start there. No, it started much earlier, when i was a kid She had this one flower, a white rose. Her favorite. She kept it by the kitchen window, where the sun hit it perfectly every morning. She’d talk to it, touch it gently, smile at it like it was a child. Like it was me. I remember watching her, waiting for her to notice me standing there. She never did. Her whole world was that flower. So one day, I broke it. I just.. snapped the stem i was jealous i wont bother to lie at that point, And she turned around like I’d killed someone. Her face, I’ll never forget it. That sadness, that disbelief. She cried. Over a flower. Not me. Not the bruises I had, not the nights I sat quiet just to keep the peace, no, she cried for a flower. That’s when it started. That’s when I knew I could bleed and she’d still water that damn plant before she’d look at me.

Before she died, she told me something. “If you ever feel sad,” she said, “pick a flower and count the petals. By the time you reach the last one, your sadness will go away.” Sweet, isn’t it? The kind of motherly nonsense people write on sympathy cards. I tried it once. After the funeral. Picked one of her flowers from the pile of pity the neighbors left. I sat there and counted, one petal, two, three, four.. By the time I reached the last one, my fingers were shaking, my palms were full of pieces, and nothing had changed. The sadness was still there. That flower didn’t take anything away it just gave me another reason to hate them.

Now, every time I see one, I feel it again that twist in my chest. I hate how they look at you, how they stand there pretending to be gentle. They’re useless. Pointless. They die for attention. They exist to make people feel better about pain they’ll never fix. People give them when they don’t know what else to say, when they’re guilty. When they’re lying. Flowers are like apologies that wilt before you can believe them. I’ve seen people cry over flowers. Smile over them. Hold them like they matter. But to me, they’ll always smell like the day I learned I wasn’t enough. That’s all they are beautiful reminders of things that die, no matter how much you water them.

So yes, I hate flowers. I hate how soft they are. I hate how easily they break. I hate that everyone forgives them for it. Because if I broke as easily as they do, no one would call it beautiful.

Ahmed

Book Review - Ghost Station by S.A. Barnes

from John Watson's Haunted Clubhouse

The first 100 pages or so set up the main character, Ophelia Bray, and the strained relationship with her wealthy family. She leaves it all behind to embark on a mission to investigate an alien planet. Her goal is to study an ailment known as ERS, while she continues her work as a therapist to the small crew on the ship.

Things bog down rather quickly, as Bray comes off as someone ill-equipped for her profession, as her head is filled with self-doubt and self-loathing, both of which are repeated ad nauseum, to the point that you end up not caring for the woman who is central to the entire story.

The whole ERS detail, which could have been interesting, fizzles away as we begin to find out that not all is as it seems on the abandoned planet with mysterious towering structures. By the time I reached this point, I was rooting for all the the people involved in the mission to perish.

I will say that Barnes is a very good writer, and I will almost certainly give her another shot. For me, Ghost Station was too slowly paced for my tastes, and did not deliver much in the way of horror or redeeming characters. Save for a few tense set pieces, this book fell flat for me.

3 Stars Out Of 5

生活リズムを立て直すはずが…・2025

from  Telmina's notes

Telmina's notes

10月5日~6日の超小旅行も終わり、昨日・7日(火)からはいよいよ生産的な行動をするはずだったのですが、気がついたら惰眠をむさぼっていた上に、PC(Mac含む)をいじったりゲームをしたりAIお絵描きをしたりしているうちに、一日が終わってしまいました。

自分は昨年8月も仕事が無く無収入の期間でした。そのときにも生活リズムの立て直しをしなければならないと述べておりましたが、そのときの反省、ぜんっぜん活かされていません。

しかも今回は昨年8月にしようとしていた引越(結局未遂に終わったが…)の計画もなく、何もせずに月末まで過ごそうとすればできてしまいます。

仕事探しについても、営業会社任せにせずにある程度能動的に探さなければならないのですが、昨日はそんな気力もありませんでした。

しかしこんなことばかり言っていると、また昨年みたいに無収入期間が想定外に延びることになってしまいます。今回は奴隷労働から解放されたことを受けての休養期間という位置づけのため、無収入期間は今月限りで終わらせたいです。

改めて、己を律せなければならないことを痛感しております。そのためにも、生活のリズムを立て直さなければなりません。それもできるだけ軽快に。

This image is created by Stable Diffusion web UI.

改めて今月やることを整理したい。

月初に述べていた「今月やろうとしていること」を、改めて見返してみます。

月初に述べていたこととその消化状況について。

- 必須

- 部屋掃除 【いちおう済】

- 青色申告ソフトへのデータ投入 【済】

- 私自身が運営するMastodonサーバーのメンテナンス

- その他

- 営業会社へのスキルシート提出 【済】

- 敢えて「何もしない日」を設ける (2日間実施)

- 無理にやる必要があるわけではないが、できれば手を出しておきたいこと

- 積みゲーの消化

- 小旅行 【済】

- ゲーム制作趣味への復帰 (たぶんやらない)

まだ実施していないものに限りピックアップすると、こうなります。

- 必須

- 私自身が運営するMastodonサーバーのメンテナンス

- 無理にやる必要があるわけではないが、できれば手を出しておきたいこと

- 積みゲーの消化

- ゲーム制作趣味への復帰 (たぶんやらない)

私自身が運営するMastodonサーバーのメンテナンス

私は分散型SNSプラットフォーム「Mastodon」を用いていくつかサーバーを運営しております。

そのひとつに、「LIBERA TOKYO」という、リベラル(自由主義者)向けコミュニティがあります。

こちらについては、やや古い基盤の上で無理矢理動かしているため、リプレイスが必要となります。

それについては、本日中に、「LIBERA TOKYO」および「info.LIBERA.tokyo」にて告知することにしますが、事前に述べておきますと、10月11日(土)の夕方頃に実施しようと思います。

積みゲーの消化

前々から、数年間積みっぱなしの「Wizardry外伝 五つの試練」をいい加減に始めたいと述べております。

しかし、こちらについての実現可能性が少し下がりました。

といいますのも、「モンスターハンターワイルズ」で特定のモンスターをなかなか倒すことができず、武具を作るための素材を入手できていないためです。そちらを優先させたいと考えているため、「Wizardry外伝 五つの試練」着手はさらに後ろ倒しになりそうです。

もっとも、そのモンスターを討伐するクエストは常設配信らしいので、別に無理に今月中に倒さなくてもいいかもしれません。むしろキャラクターメイキングが面倒なWizardryのほうを今月中にやってしまうべきか。

ゲーム制作趣味への復帰 (たぶんやらない)

一応リストアップしましたが、自作ゲーム制作趣味の復帰は恐らくしません。上記の積みゲー消化で限界だと思います。

できるだけ早めに11月からの仕事を決めたいところだが…

昨年8月の時は、なかなか9月スタートの仕事が見つからず、結局無収入期間を1ヶ月延ばしてしまい、あちこちに迷惑を掛けることになってしまいました。特に引越を断念したことで、お世話になるはずだった業者には無駄働きをさせてしまい、本当に申し訳なく思います。

とはいえ、焦って条件の良くない仕事を請けてしまうとまた同じことの繰り返しになってしまうため、仕事を請けるときはちゃんと条件面に注意したいです。

#2025年 #2025年10月 #2025年10月7日 #ひとりごと #雑談 #生活習慣 #仕事 #青色申告 #確定申告 #ゲーム #SNS #分散型SNS #Fediverse #Mastodon #マストドン #LiberaTokyo #自由主義 #リベラル #旅行

The Ninth

I forgot it was your birthday. For years, this day would ruin me. But this time-

I forgot it was your birthday.

I forgot to remember.

I stopped keeping count.

Dotdrop for dotfiles

from  in ♥️ with linux

in ♥️ with linux

I use two computers: a desktop and a laptop.

Both computers should always be synchronized. Syncthing takes care of my files (music, images, documents), but the configurations should also always be the same.

Many Linux programs store their settings in the hidden .config directory. However, I don't want this folder to be completely synchronized, just individual files ... so called dotfiles.

This is where dotdrop comes in.

Dotdrop is a dotfiles manager that provides efficient ways to manage your dotfiles. It is especially powerful when it comes to managing those across different hosts. The idea of dotdrop is to have the abilit``y to store each dotfile only once and deploy them with different content on different hosts/setups.

Put simply, dotdrop makes a copy of the file in a specified directory and also takes care the permissions. This directory can then be synchronized between two computers using git (or any other tool).

It uses the hostname as the profile. This means that the configuration can also be used to specify which computer the file should be installed on.

Add a file to dropdrop

dotdrop import FILENAME

This adds to the profile of the current computer. However, a different profile (usually the host name of the other computer) can also be specified during import.

dotdrop import --profile=HOSTNAME FILENAME

The config file can be put in ~/.config/dotdrop/, among other places. However, since I also push other things to git (Codeberg) via this directory, I decided to use ~/.dotdrop.

I also use two configuration files: one for user files and one for system files.

dotdrop import --cfg=~/.dotdrop/config-user.yaml FILENAME

or

dotdrop import --cfg=~/.dotdrop/config-root.yaml FILENAME

Remove a file to dropdrop:

Also very simple. Just go to the correct folder and

dotdrop remove FILENAME

Installing a file

Once the file has been assigned to the corresponding profile in the configuration file, it is installed on the computer using the following command. Before doing so, it is of course advisable to execute a git pull to ensure that the current file has been loaded into the dotdrop folder.

dotdrop --cfg=~/.dotdrop/config-user.yaml install

Or for systemfiles:

sudo dotdrop --cfg=~/.dotdrop/config-root.yaml install

Customisation

The great thing about dotdrop is that it is very easy to integrate into your own scripts. For example, I did not find that the file is always automatically added to all profiles during import. Perhaps this is possible by default, but I did not find anything about it in the documentation.

So I simply execute the command twice with this script:

#!/bin/bash

CONF="~/.dotdrop/config-user.yaml"

PROFILES=(

"hostname1"

"hostname2"

)

for prof in "${PROFILES[@]}"; do

dotdrop import --cfg=$CONF --profile=$prof $1

done

dotdrop --cfg=$CONF profiles

Conclusion

There are similar tools to dotdrop. The best example is chezmoi, which I really enjoyed using on openSUSE. However, this is not included with Debian. It was a bit of a shame at first, but now I like the simplicity of dotdrop.

from Dzudzuana/Satsurblia/Iranic Pride

Narzissmus und die Leere der Herkunft

In einer Welt, in der sich alles um Darstellung dreht, scheint Ehrlichkeit fast wie ein Anachronismus.

Man begegnet Menschen, die ihre Herkunft verschleiern, weil sie lieber in vielen Spiegeln gleichzeitig schimmern wollen, statt sich in einem einzigen klar zu erkennen.

Der Narzissmus unserer Zeit liegt nicht mehr nur in der Selbstliebe, sondern in der Angst vor Tiefe – der Angst, etwas zuzugeben, das sich nicht beliebig ändern oder verbessern lässt.

Wenn Identität zur Bühne wird, verlieren Herkunft, Sprache und Geschichte ihren Wert.

Die Zugehörigkeit, die früher Halt gab, wird ersetzt durch Rollen, Masken, wechselnde Profile.

In dieser Atmosphäre wirkt jeder Versuch, etwas Authentisches über sich selbst zu sagen, fast naiv – oder gefährlich.

Denn wer sich bekennt, macht sich verwundbar; wer sich maskiert, bleibt unangreifbar.

Doch wer die Wahrheit sucht, tut das nicht aus Eitelkeit.

Er sucht, weil er spürt, dass hinter all den Spiegeln etwas fehlt – etwas, das man nicht inszenieren kann.

Vielleicht ist genau das der Gegenpol zum Narzissmus:

nicht Selbstliebe, sondern Selbstaufrichtigkeit.

Nicht Bewunderung, sondern Verwurzelung.

Denn echte Identität glänzt nicht. Sie hält.

Living in a Catholic Monarchy

from  CSF Quarterly

CSF Quarterly

We are called to be leaven in our more local democratic republic

We live in a Catholic monarchy. Jesus our Christ is our King, our Blessed Virgin Mother our Queen. True, in the United States, our local government is, of the moment, if we can keep it, a democratic republic, with regions devolving into anarchy courtesy of modernism's progressivism. Yet, we all, each and every one, regardless of belief, live in a Catholic monarchy. This realization likely leaves us with a lot to (re)examine, including history, monarchy, some of our cherished human rights, and how we Catholics answer Christ's call to be in the world but not of it.

An overarching Catholic monarchy lived by Catholics threatens and terrifies tyrants and anarchists, other despots, and those whose delusions depend on God's non-existence. Interestingly enough, this terror of the Truth (Love, Justice, and Mercy) is part of the proof of the Truth. Catholics, therefore, appear to “hate” much in the modern world, when we love one another as Christ has loved us (Jn 13:34). Pride has those deluded by the various poisons of the fallen world needing to rule at the top; be it a kingdom of many or, in the case of nihilists and anarchists, an ever dwindling kingdom of one.

Monarchy is the governance model God gives us, and He freely shares His authority. He appoint husbands as head of house to love their wives as Christ loves His Church (Eph 5), priests, bishops, and our pope, all as ruling shepherds over the sheep entrusted to them by Christ.

A brief history may help, for modern history ignores the Catholic Golden Age, claiming it was part of the Dark Ages. For 1,200 years, from Charlemagne in 600 to the last vestiges ended unjustly after World War 1 due to the fear and hatred described above, the Holy Roman Empire served her people in various forms and imperfections. Yet, by the grace of God working through His authority on earth, she ushered in a Catholic Golden Age, out of the Dark Ages following the fall of the Roman Empire. Agriculture and trade developed and flourished, universities and hospitals formed, various sciences emerged—advances that occurred nowhere else.

Out of the Dark Age, the Church upheld and recognized and aided the rising authority of Catholic monarchs. Pope Leo XIII, pope from 1878 to 1903, explains: “...when Christian rulers were at the head of States, the Church insisted much more on testifying and preaching how much sanctity was inherent in the authority of rulers” (Diuturum Illud, No. 21) So much so that “Obedience to authority is obedience to God” (Ibid. No. 27).

As Pope Leo XIII explains: “...from the time when the civil society of men raised from the ruins of the Roman Empire, gave hope of its future Christian greatness, the Roman Pontiffs, by the institution of the Holy Roman Empire, consecrated to political power in a wonderful manner. Greatly, indeed, was the authority of rulers ennobled; and it is not to be doubted that what was then instituted would always have been a very great gain, both to ecclesiastical and civil society, if princes and peoples had ever looked to the same object as the Church. And, indeed, tranquility and a sufficient prosperity lasted so long as there was a friendly agreement between the two powers” (Diuturum Illud, No. 22).

Pope Leo XIII goes on to explain the checks and balances on the State, as well as the people: “If the people were turbulent, the Church was at once the mediator for peace. Recalling all to their duty, she subdued the more lawless passions partly by kindness and partly by authority. So, if, in ruling, princes erred in their government, she went to them and, putting before them the rights, needs, and lawful wants of their people, urged them to equity, mercy, and kindness. Whence, it was often brought about that the dangers of civil wars and popular tumults were stayed” (Ibid.)

Arguably, we have fallen into a new Dark Age, under the weight of Martin Luther's attack on God's authority on earth, in the form of the Sola Heresies (I refer to them this way as each of his heresies' first word is “sola”: scriptura, fide, gratia). Pope Leo XIII again explains: “...the doctrines on political power invented by late writers (of the so called Enlightenment and Rationalists) have already produced great ills among men, and it is to be feared that they will cause the very greatest disasters to posterity. For an unwillingness to attribute the right of ruling to God, as its Author, is no less than a willingness to blot out the greatest splendor of political power and to destroy its force. And they who say that this power depends on the will of the people err in opinion first of all; then they place authority on too weak and unstable a foundation...From this heresy (the Sola Heresies of Martin Luther) there arose in the last century a false philosophy—a new right as it is called, and a popular authority, together with an unbridled license which many regard as the only true liberty. Hence we have reached the limit of horrors, to wit, Communism, Socialism, Nihilism, hideous deformities of the civil society of men and almost its ruin” (Ibid. No. 23).

This shocks the modern mind: A Catholic monarchy has more immediate and effective checks and balances on it than are built into the Constitution of the United States. A Catholic monarch strives to have bold, humble obedience to God, including His Church, the royal family, and the people of God. Read the writings of the Reigning Prince of Liechtenstein Hans-Adam II in The State in the Third Millennium and The Habsburg Way by Eduard Habsburg, Archduke of Austria and they also describe the workings of these checks and balances of a Catholic monarchy by God's authority on earth.

To understand history, and the rise and eventual neutering of Protestant monarchies, we need only understand that Martin Luther's Sola Heresies evaporated these checks and balances, leaving Protestant monarchs deluded into believing they alone were the highest authority to interpret God's revelation, something no good Catholic would do (keeping in mind Christ Himself defers to the will of the Father).

Is a Catholic monarchy perfect? Not this side of death's veil; it is, however, the best governance model there is, divinely instituted. As near as I can see, based on the nurturing and defense of obedience to God's authority on earth in each: Catholic monarchy > democratic republic >> Protestant monarchy >>>> all others.

As with any shifting and developing relationship, the emergence of a Catholic emperor caused challenges as the papacy and monarchy sorted out how and where authority flowed. Much the same long term learning is occurring in these recent centuries between emerging democratic republics and the papacy and society at large, especially with the added shift of the disenlightenment and rise of irrationalism that now infuses society. Time and experience improved the relationship with the Holy Roman Empire through the centuries, as both chose bold, humble obedience to Christ and thus learned and improved how each filled their divinely appointed office.

Jump forward to the current challenge between the papacy and modernist society: Is similar improvement possible when one of the parties rejects the existence of God? Improvement depends on bold, humble obedience to Christ; thus, the question becomes one of how to shepherd a wayward child who has turned away from Truth, Love, Justice, and Mercy. How did this happen? Since 1517, society has been in decline, not ascent. Authority—which is only granted by God—on earth, the Church, Catholic monarchies, and in individuals, was attacked by Martin Luther's Sola Heresies. The Church has reeled since with how to shepherd. How does one shepherd amidst the confusion of modernism? Naming and lamenting the errors, including that only the individual can discern Truth and the authority to rule derives from the people, not from God, is a start, yet how do we answer Christ's call of the spiritual act of mercy to “admonish the sinner”? Shepherding people out of modernism's many errors is akin to parenting a wayward teen running with the wrong crowd, relishing sex, drugs, and violence.

In theory, in a democratic republic, a well formed, faithful people have a collective authority of sensus fidelium, sense of the faithful, in discerning how they vote (the same authority that is a check and balance against a wayward Catholic monarch); yet when society erodes the “fidelium”, the authority decreases; so to, as leaders have less or no fidelium, what authority they had also erodes, for they have no Christ compass to recognize Truth, Love, Justice and Mercy.

Pope Leo XIII explains part of the root of this shepherding challenge with the many flavors of modernism—including liberalism, progressivism, communism, socialism, nihilism, and anarchy—“For fear, as Saint Thomas (Aquinas) admirably teaches 'is a weak foundation: for those who are subdued by fear would, should the occasion arise in which they might hope for immunity, rise more eagerly against their rulers, in proportion to the previous extent of their restraint through fear'” (Diuturum Illud, No. 24). With diminished authority, fear of punishment is the remaining motivation to obey to the law and there is no motivation to obey what is just.

This explains the chaos of our time. How, then, are we to be Catholic in a local democratic republic? Firstly, we ought always remember we are within the rule of Christ our King. Secondly, much as early Christians were faithful leaven as citizens of the Roman Empire, which persecuted them, we called to be leaven.

Saint Alphonsus De Liguori described Saint Sebastian's martyrdom: “Sebastian answered that he considered he was rendering the greatest possible service to the emperor (as a soldier), since the state benefited by having Christian subjects, whose fidelity to their sovereign is proportionate to their devotedness to Jesus Christ. The emperor, enraged at this reply, ordered that the saint should be instantly tied to a post and that a body of archers should discharge their arrows upon him” (Victories of the Martyrs, Ch. LXII).

In more modern times, Pope Leo explains: “The Church of Christ indeed cannot be an object of suspicion to rulers, nor of hatred to the people; for it urges rulers to follow justice, and in nothing to decline from their duty; while at the same time it strengthens and in many ways supports their authority” (Diuturum Illud, No. 26).

As faithful Catholics, our challenge is to be formed by the Church. We are called to turn to the shepherds Christ entrusts us to so Christ, through them, may shepherd us. As we become more formed, we become leaven throughout society. No matter the local government, or the state of society, Christ within us rises, elevating society. This is how the Church can shepherd manfully amidst these modern errors, and how we faithful can be manfully shepherded. Who but Christ through His Church can name error of our modern ways? For we hold as cherished rights these errors, so turned around by Satan are we: the supposed even plane of ideas, the individual as the highest authority of Truth, and the people, not God, as the source of authority to rulers, among others.

We Catholics are called to elevate public discourse, both with how we live our lives and how we converse with others who do not yet understand. We ought never entertain the voice and temptation and lies of Satan in modernism's many flavors. To modernist eyes, any just voice elevating discourse spouts authoritarian hate. To anarchists, everything looks like fascism.

We Catholics are called to be leaven. Let us turn to our shepherds to form us, that by living our Faith we elevate the city of man, in which we live but are not of, toward becoming the City of God, by being the light of Christ on the hill.

Now, how do I get this bushel off my head?

May Christ startle you with joy!

#BlessedVirginMary #CurrentEventsTimelessTruth #HumanEndeavor #Catholic #Monarchy #Shepherding #CSFSymposium #Communism #PopeLeoXIII #Nihilism #Modernism #Progressivism #MartinLuther #Habsburg #Lichtenstein #DarkAge #GoldenAge

from Dzudzuana/Satsurblia/Iranic Pride

Yaşar Kemal: Language, Region, and the Politics of Recognition

Yaşar Kemal (1923–2015) is one of the most influential novelists of modern Turkish literature. Born in the village of Hemite (now Gökçedam) in the province of Adana, his family had migrated there from Van in eastern Anatolia after the First World War. This biographical detail—roots in Van and life in Adana—has led to long-standing discussions about his ethnic background and the regional mix of influences that shaped his imagination.

1. Van and Adana: Two symbolic geographies

Van, near the Caucasus, is a crossroads where Kurdish, Armenian, Azeri, and Turkish communities have historically lived side by side. Adana, on the other hand, lies in Çukurova, the fertile plain of southern Turkey, where migrants from eastern Anatolia, Turkmen tribes, Arabs, and Kurds settled during the Ottoman period and the early Republic. Kemal’s movement from Van’s frontier culture to Adana’s agrarian plain mirrors a wider demographic pattern of the 20th century. It also created the dual sense of belonging and displacement that pervades his novels.

2. Ethnic origin: what is known and what is conjecture

Most scholars agree that Kemal was born into a Kurdish-speaking family that later adopted Turkish in daily life. He himself described his family as Kurdish in several interviews, though he also emphasized that he considered language and culture, not ethnicity, to be the basis of identity. Because Van historically included Azeri-speaking Muslim populations and Turkish-speaking migrants, some commentators have speculated about mixed Caucasian or Azeri ancestry, but there is no documentary or genetic evidence for this. Kemal never publicly identified as Azeri or Turkish by ethnicity; he referred to himself as a writer of the Turkish language.

3. Writing in Turkish and the politics of language

Although he grew up hearing Kurdish and Turkish dialects, Kemal chose to write exclusively in Turkish. This decision was partly practical: Kurdish publishing was forbidden in the early Republican decades, and the literary market, education system, and publishing houses all operated in Turkish. His use of Turkish allowed him to reach a national audience, but it also caused later readers to question whether he could represent Kurdish experience authentically. In his works such as İnce Memed (1955), the social landscape—landlords, villagers, rebellion—draws heavily on the oral storytelling of Kurdish and Anatolian traditions, even when the language of narration is Turkish.

4. Fame and reception

Kemal’s fame within Turkey owes much to the fact that he wrote in Turkish at a time when the state strongly promoted Turkish-language culture. Yet his humanistic and socially critical themes—poverty, resistance, the dignity of rural life—resonated far beyond nationalist boundaries. Internationally, he was celebrated as a voice of the oppressed and was nominated several times for the Nobel Prize in Literature. Within Turkey, his popularity was exceptional for an author of Kurdish origin, but his universalism and avoidance of overt ethnic politics made his acceptance by Turkish readers possible.

5. Identity and legacy

To view Kemal simply as “a Kurd who became famous among Turks” or “a Turk with eastern roots” misses the complexity of his life’s work. He belonged to a generation that lived through the suppression of minority languages and thus learned to express local realities through the dominant tongue. His identity can best be described as culturally Kurdish, linguistically Turkish, and humanist in outlook. Rather than denying his origins, Kemal transformed them into a bridge between Anatolia’s diverse peoples.

6. Conclusion

Yaşar Kemal’s story illustrates how literature in multilingual societies often travels through the language of power while preserving the memory of other tongues. Whether Kurdish, Turkish, or mixed in ancestry, he embodied the paradox of modern Anatolia: the coexistence of repression and creativity, loss and articulation. His fame among Turkish audiences was not proof of assimilation alone, but of a literary genius who turned personal displacement into a universal language of justice and endurance.

Mediated Speech and Deferred Presence: Kurdish Language Use Across Distance --

from Dzudzuana/Satsurblia/Iranic Pride

-—

Abstract

This essay explores the paradoxical phenomenon in which many Kurds freely speak Kurdish through mediated channels—phone calls, voice messages, livestreams, or social media—yet remain silent in face-to-face interactions. Drawing from sociolinguistic theory and digital ethnography, the paper argues that this “mediated courage” reflects a transitional state of post-repression identity: communication becomes possible only when the body of risk is removed from physical space.

-—

1. Introduction

In many diaspora and regional Kurdish contexts, an observable pattern emerges: individuals who avoid speaking Kurdish publicly will nevertheless do so fluently and confidently over the phone or in online spaces. The digital or acoustic distance functions as both a shield and a permission structure. While physical spaces remain contaminated by historical fear, mediated spaces simulate safety.

-—

2. The Psychology of Distance

Direct speech carries immediate social exposure: tone, volume, and accent become visible markers of identity. By contrast, mediated communication creates what sociologist Erving Goffman called a “frame of detachment”—a situation in which one’s speech no longer feels fully embodied or surveilled.

For Kurds, this distance transforms the suppressed instinct of caution into expressive potential. The absence of witnesses grants the speaker a sense of temporary autonomy; Kurdish can exist without consequence.

-—

3. The Role of Technology

Smartphones and social platforms have inadvertently become tools of linguistic emancipation. Voice notes, WhatsApp groups, and TikTok videos allow speakers to select their audience and control their vulnerability. This produces a new linguistic category: digitally mediated Kurdish—a form that thrives in private networks but rarely crosses into shared, physical soundscapes.

However, this mediation also fragments community. While Kurdish gains visibility in virtual environments, it remains largely inaudible in cafés, classrooms, and public squares. The result is a paradoxical landscape: an abundance of digital Kurdish words and a scarcity of Kurdish voices in real life.

-—

4. Mediated Courage and Deferred Freedom

This behaviour illustrates a liminal stage in the process of recovering linguistic agency. Speaking Kurdish through media is an act of mediated courage—a safe rehearsal for the public freedom that does not yet exist. It reveals both progress and hesitation: progress, because the language is alive and circulating; hesitation, because the body still fears its own voice.

-—

5. Diasporic Echoes: Toward Linguistic Sovereignty

Migration has displaced not only Kurdish bodies but the acoustic landscape of Kurdish identity. In the diaspora, the right to speak freely exists on paper, yet many Kurds still hesitate to let Kurdish fill public air. The inherited instinct of caution survives even where censorship no longer does. The result is a paradoxical freedom—one that grants expression but not confidence.

5.1 The Paradox of Safety Abroad

In Europe, Kurdish can be taught, printed, or sung without legal restraint, yet its speakers often default to the more “recognized” languages around them. Silence has evolved from prohibition into habit; the border once patrolled by the state now runs invisibly through self-restraint. Sovereignty, therefore, is not measured by laws but by how easily one can speak without translating oneself.

5.2 Multiplicity as Survival

Kurds in exile carry dialectal diversity—Kurmanji, Sorani, Zazaki—each shaped by a different colonial history. When they meet, they translate within their own nation, revealing both the fracture and the resilience of Kurdish identity. What outsiders call fragmentation is, in reality, a living record of endurance. Sovereignty will emerge not from uniformity but from the recognition that plural voices can still form one chorus.

5.3 From Digital Voice to Embodied Speech

Online, Kurdish thrives in podcasts, TikTok lessons, and Clubhouse debates. The internet has become a temporary homeland of sound, a rehearsal space for free speech. Yet linguistic sovereignty demands embodiment—the moment when a digital phrase becomes a street conversation. The next phase of revival lies in transferring digital courage into public space, until the Kurdish voice becomes as ordinary as any other.

5.4 Reclaiming the Ordinary

The final step beyond enabled silence is not heroic proclamation but casual fluency—greetings, humour, marketplace chatter. When Kurdish re-enters these small, habitual exchanges, it ceases to be a memory and becomes a daily fact of life. True sovereignty begins when the language no longer needs permission to exist.

-—

6. Conclusion: From Mediated Speech to Linguistic Sovereignty

The phenomenon of speaking Kurdish through mediated distance—phone calls, online spaces, or recorded messages—reveals that silence has not disappeared; it has merely shifted its geography. The Kurdish voice today exists between screens and borders, between the memory of repression and the simulation of safety. To speak Kurdish in private audio but not in public space is to live in a half-freedom: the words survive, yet the sound remains confined.

This condition reflects a deeper historical continuity. Even outside the geopolitical borders that once censored Kurdish speech, the psychological border persists. The instinct to lower one’s voice, to switch to another language, or to self-translate has outlived the state policies that first imposed it. Silence, in this sense, has become cultural muscle memory—unlearned only through deliberate practice and collective re-embodiment.

Yet, the proliferation of Kurdish through digital and diasporic channels signals a quiet transformation. Every voice note, livestream, and online lesson contributes to a growing archive of linguistic presence. This is not merely the revival of a language but the return of a soundscape: Kurdish rediscovering its resonance in both the digital ether and, slowly, in physical air.

The long-term challenge for revitalization lies in translating this virtual fluency into embodied presence—so that Kurdish can inhabit streets, homes, and public life with the same confidence it already holds online. True linguistic sovereignty will not arrive through institutions or declarations, but through the normalization of Kurdish in daily speech. When the language can exist without apology, without translation, and without fear, enabled silence will finally give way to enduring voice.

References

Ammann, M. (2022). Language and Power in the Middle East: Ethnolinguistic Dynamics of Kurdish Communities. London: Routledge.

Blommaert, J. (2010). The Sociolinguistics of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bozarslan, H. (2016). Kurdish History and Identity: A Transnational Perspective. In M. Casier & J. Jongerden (Eds.), Nationalisms and Politics in Turkey (pp. 135–152). New York: Routledge.

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

→ (Used for the “frame of detachment” concept.)

Haig, G., & Öpengin, E. (2018). Kurdish: A Critical Research Overview. Kurdish Studies, 6(2), 99–122.

Hassanpour, A. (1992). Nationalism and Language in Kurdistan, 1918–1985. San Francisco: Mellen Research University Press.

→ (Foundational for linking Kurdish language suppression to state policy.)

İsmail, D. (2020). Digital Kurdish: Language Activism in the Age of Social Media. International Journal of Kurdish Studies, 6(1), 45–63.

Moriarty, M. (2014). The Politics of Multilingualism: Linguistic Governance in Contemporary Europe. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Scalbert-Yücel, C., & Hassanpour, A. (2008). Kurdish Language Policy in Turkey: Political Choices and Sociolinguistic Consequences. Language Policy, 7(3), 281–301.

Spolsky, B. (2018). Language Policy in Modern Times: Theory and Practice. New York: Routledge.

Van Bruinessen, M. (1998). Shifting National and Ethnic Identities: The Kurds in Turkey and the Diaspora. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, 18(1), 39–52.

Semantics at the Edge

from  stackdump

stackdump

When you send a packet across a network, nobody in the middle knows what it means. Routers forward bytes, proxies cache responses, CDNs balance load — but meaning never travels with the message. It only appears when the packet reaches an agent that knows how to interpret it.

The same is true of URLs. A query string is just an encoded intention — a compact expression of state and purpose — until it’s decoded by a viewer, a realm, or a mind. Every layer between creation and comprehension is an opaque tunnel.

In the Logoverse, we make this principle explicit. A glyph is a semantic packet: sealed, transportable, and interpretable only at the edge — the place where code and consciousness meet. The meaning doesn’t live in the data; it emerges at the boundary that knows how to see.

Semantics at the edge is not a limitation — it’s the design of the universe. Everything between sender and receiver is structure. Meaning happens where you stand.

I want to keep my streak of daily posting

from  Enjoy the detours!

Enjoy the detours!

So, here is my unnecessary post to keep my personal streak running.

Quite busy today, so it's challenging to write something between my appointments.

But I wish everyone who reads this a nice day. 😎

32 of #100DaysToOffload

#log

Thoughts?

from Dzudzuana/Satsurblia/Iranic Pride

Abstract

This paper explores the phenomenon of intergenerational linguistic inhibition among Kurds who grew up without knowledge of their ancestral language despite identifying strongly with Kurdish heritage. Drawing on sociolinguistic theory and trauma studies, it argues that the modern inability to retain or internalize Kurdish vocabulary is not a matter of individual capacity but the result of historically conditioned repression. Beginning with the language bans of the Atatürk era, Kurdish was systematically excluded from public life and stigmatized within private spheres. Over successive generations, fear of punishment and social exclusion evolved into self-censorship, leading families to suppress the language voluntarily. This internalized prohibition—what the paper terms enabled silence—continues to manifest neurologically and emotionally, impeding language acquisition even among those seeking to relearn Kurdish in adulthood. The study concludes that Kurdish language revitalization cannot rely solely on pedagogy; it requires the restoration of cultural confidence and the unlearning of imposed fear—a process of reclaiming speech as an act of freedom rather than permission.

from Dzudzuana/Satsurblia/Iranic Pride

Enabled Silence: Mechanisms of Linguistic Self-Suppression Among Kurds in the Post-Assimilation Era

-—

Abstract

While external repression of Kurdish identity through state policies has been widely documented, the phenomenon of self-suppression within Kurdish households remains understudied. This paper examines how sociopolitical systems in Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran historically enabled Kurdish families to abandon their mother tongue voluntarily, transforming imposed silence into an inherited behavior. By analyzing institutional, psychological, and symbolic mechanisms of control, this paper argues that the true divide among Kurds today is not geopolitical, but linguistic: between those who retained Kurdish as a medium of identity and those whose families internalized its repression.

-—

1. Introduction

The Kurdish question has traditionally been analyzed through territorial and political frameworks: partition, nationalism, and minority rights. However, beneath these macro-level divisions lies a subtler process of identity fragmentation — the linguistic disconnection between Kurds who speak Kurdish and those who do not. This divide transcends national borders and persists in diasporic communities. It is not merely the product of overt prohibition but of long-term social engineering that made silence appear rational, patriotic, and even virtuous.

-—

2. Historical Context of Linguistic Repression

Following the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), emergent nation-states such as Turkey, Iraq, and Iran embarked on homogenization projects to consolidate state identity. Kurdish was banned from education, administration, and media. In Turkey, Law No. 2932 (1983) criminalized public use of Kurdish until the early 1990s, while in Syria, the Ba‘ath regime denied Kurds citizenship and restricted Kurdish publications. These policies sought not merely to silence the Kurdish language, but to replace it with official state languages as symbols of loyalty.

The assimilation process, however, did not end with the repeal of legal bans. Instead, its logic was absorbed into Kurdish social structures themselves. Parents, shaped by decades of fear, began to reproduce state ideology at home — an outcome that Michel Foucault would describe as the internalization of disciplinary power.

-—

3. The Institutional Enablers of Silence

3.1 Education as Cultural Conditioning

School systems were the primary vector of linguistic assimilation. Textbooks portrayed national identity as monolingual and unitary. Kurdish children, punished or humiliated for using their mother tongue, quickly learned to compartmentalize: the public language became a symbol of success; Kurdish, of backwardness. In many households, this hierarchy persisted long after formal bans were lifted.

3.2 Bureaucratic Assimilation

Access to economic and social mobility required compliance with official linguistic norms. Kurdish names were Turkified or Arabized; state documents refused Kurdish orthography. In such a context, non-Kurdish fluency became a form of capital, while Kurdish speech implied social risk. Consequently, many families ceased transmitting Kurdish not out of rejection, but as an act of pragmatic adaptation.

3.3 Media and Symbolic Power

The monopolization of public discourse by state media ensured that Kurdish identity appeared marginal or even subversive. Until the 2000s, Kurdish voices were largely absent from mainstream platforms, reinforcing the perception that Kurdishness existed only in private spaces or folklore.

-—

4. Psychological Mechanisms of Internalized Repression

Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of symbolic violence provides a framework for understanding how dominated groups internalize their subordination. When linguistic repression persists over generations, fear becomes habitus — a deep-seated disposition. Families begin to police their own children, not because they reject their roots, but because they have learned that silence ensures safety.

This internalized fear produces what can be termed “enabled silence”: a state in which individuals voluntarily continue the repression once imposed upon them. The enabler is not coercion, but the memory of coercion.

-—

5. The Linguistic Divide Within Kurdish Identity

Today, the Kurdish linguistic divide manifests not as rural versus urban, nor as regional difference (Kurmanji, Sorani, etc.), but as an existential split: between speakers and non-speakers. The former can engage in activism, literature, and transnational dialogue; the latter often experience identity paralysis — they “feel Kurdish” but lack the linguistic means to articulate belonging.

This divide is exacerbated by the perception that language retention equates to authenticity, relegating non-speakers to a secondary status within their own ethnicity. The consequence is a fragmented national consciousness, where political solidarity is undermined by linguistic insecurity.

-—

6. Conclusion: Reclaiming the Right to Voice

The persistence of silence among some Kurdish families cannot be understood merely as a failure of cultural transmission; it is the result of structural conditioning. Reclaiming Kurdish identity, therefore, requires more than language revival — it demands the dismantling of the psychological and institutional mechanisms that made forgetting seem normal.

Grassroots movements, digital platforms, and diaspora initiatives have begun to bridge the divide by creating safe spaces for “language-lost Kurds.” Through music, online courses, and bilingual media, they reframe Kurdish not as a risk, but as a right.

Ultimately, the struggle for linguistic revival is not simply about words — it is about restoring the capacity to speak existence itself after generations of enforced silence.

7. Bilingual Self-Justification: The Quiet Strategy of Visibility

Another symptom of enabled silence appears in the compulsory bilingualism practiced by many Kurds who wish to make their language publicly visible.

In numerous media formats—especially on social platforms—Kurdish is almost always accompanied by a Turkish or Arabic translation.

A simple example can be found in a video by a Kurdish language teacher who states, “Ez mamosteyê Kurdî me” (“I am a Kurdish teacher”), immediately followed by the Turkish equivalent, “Kürtçe öğretmeniyim.”

This doubling is not merely a gesture of accessibility; it reveals a deeply internalized need to legitimize Kurdish through the dominant language.

Kurdish can be spoken, but only when it is instantly translated—embedded within the language of authority.

Thus, even an act of pride remains touched by the residue of justification.

This practice represents a form of post-assimilation adaptation: visibility without provocation.

It allows individuals to express Kurdish identity while staying within the perceived limits of acceptability.

Yet it simultaneously reinforces a symbolic hierarchy: Turkish or Arabic continue to function as the languages of public legitimacy, while Kurdish remains a secondary, explanatory tongue.

Within this framework, bilingual self-justification can be read as a transitional phase—a moment suspended between fear and freedom.

It shows that the silence has been broken, but the voice of the oppressor still echoes faintly within it.

Only when Kurdish can be spoken without translation, without the need to explain itself, will enabled silence truly be overcome.

-—

References (Suggested)

(These are placeholder sources you can expand depending on your academic context)

Bourdieu, Pierre. Language and Symbolic Power. Harvard University Press, 1991.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Pantheon Books, 1977.

Hassanpour, Amir. Nationalism and Language in Kurdistan, 1918–1985. Mellen Research University Press, 1992.

Natali, Denise. The Kurds and the State: Evolving National Identity in Iraq, Turkey, and Iran. Syracuse University Press, 2005.

Sheyholislami, Jaffer. Kurdish Identity, Discourse, and New Media. Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.